by Carla Dominguez

There are two main schools of thought about illusions in creative work—schools that often are in opposition. First, there is a general belief that illusion is essential to art. At the same time, it is also generally accepted that creative works, whether it be writing, visual or performance, are an essential part of truth.

It’s an interesting paradox that has been seen as a problem. Socrates asserted that artists are mere imitators that create an illusion of knowledge. Arts such as prose and poetry, he argued, distract humanity from reality and the important task of understanding the truths of the world.

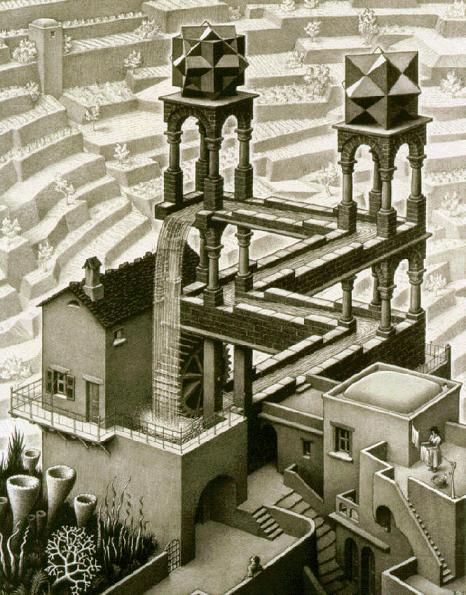

Yet not all illusions might be able to fit so neatly into the category of “untruth.” Illusions are a part of daily life and very much a part of reality. We often run into them, though perhaps we don’t always notice. Some are obvious, such as optical, graphic, visual or physiological illusions.

Others are so ingrained in our culture that we accept them without a second thought, as with the scientific illusion that the sun is setting, rather than the reality of the Earth’s rotation.

Perhaps illusion is a function of reality, helping humans understand the world and express and represent what we see or feel. It’s human nature to capture and express individual perception. And art presents truth outside of its practicality, as imaginative expression. Creative works bring out illusions we encounter every day, but routinely ignore, breaking down our thoughts about appearance and perception and their relation to reality in the observable world. Trying to separate art from reality might be counterproductive. It might make it easier to accept a convergence of art and the representation of life, and of illusion and reality.