by Carla Dominguez

Portraits have always been the most popular type of photography. Besides being an excellent preservation of our history, portraits give us permission to stare at people, quietly learning their stories.

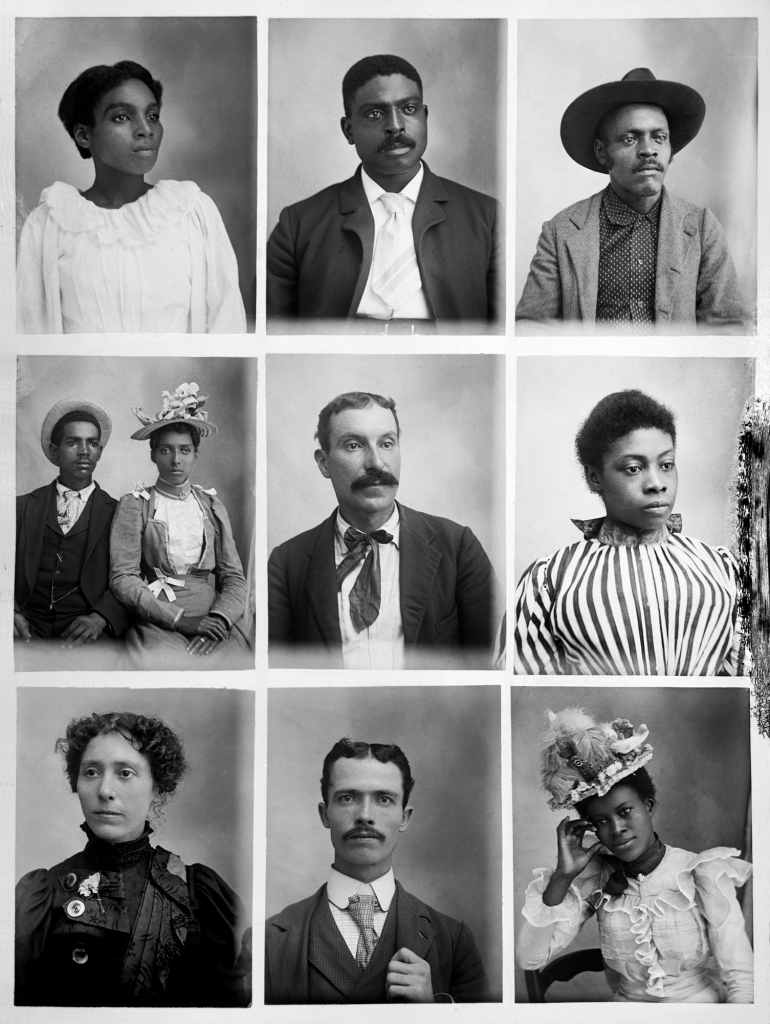

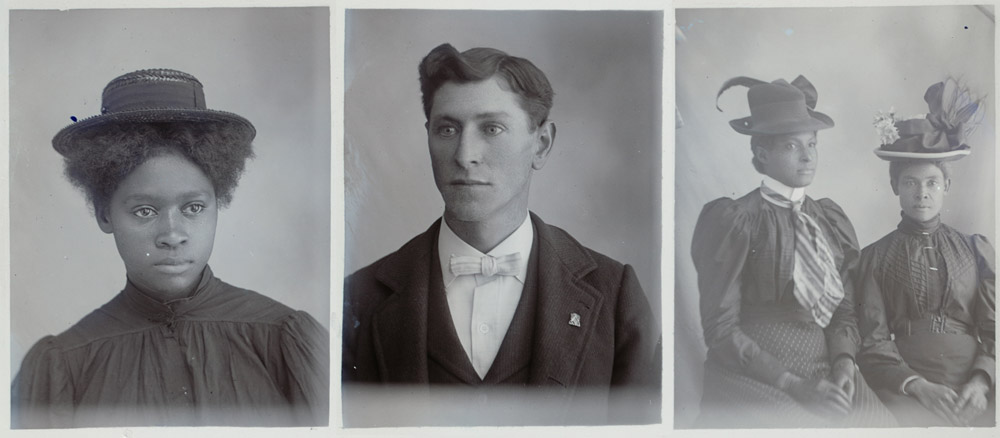

Hugh Mangum was a self-taught itinerant photographer from Durham, North Carolina who understood the truth that portraits convey. At the beginning of the twentieth century he traveled a rail circuit through North Carolina and Virginia, taking pictures along the way of a variety of people. Although it was during a time of rampant racism and strict segregation, he captured incredible portraits of all types of people, creating a rich and diverse pictorial history. They show a glimpse of a world not long after the abolition of slavery, challenging the racial barriers in the deep South, and capturing the diversity of people.

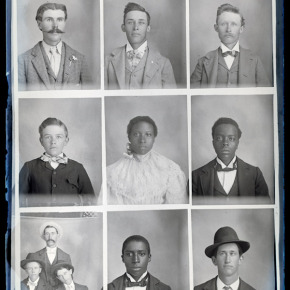

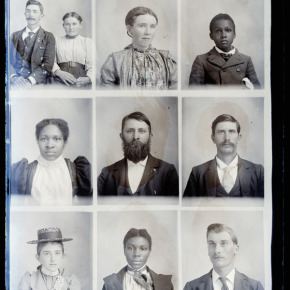

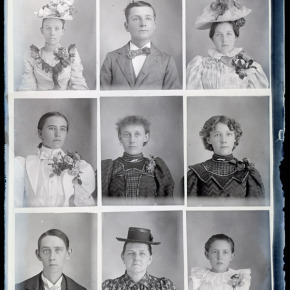

Viewing them we are transported to the past, connecting with these nameless subjects. Magnum photographed people black and white, poor and rich, some humorous, others quite serious. He used a Penny Picture Camera, which allowed for individual sections of a glass plate negative to be exposed at different times. Using a single negative for multiple photographs kept costs for photographs low, making them relatively affordable. He likely took and exposed thousands of glass plate negatives, but many of them have been lost or destroyed, including the meticulous records of names that came with them. Around 700 glass plate negatives survived, salvaged from the pack house where Mangum kept his darkroom.

The layout of the images on Mangum’s negatives show the sequence in which the photographs were taken, revealing the order that people entered his studio and showing that all kinds of people would wait together to have their own personal piece of history. But perhaps the most important aspect of Mangum’s portraits was the way that each person, regardless of race, or social standing, was presented in dignity. For Mangum’s black or poor clients, a studio portrait was one way to showcase their dignity, beauty and individuality. The prints would have been given to them to the subjects, to share with the family, to keep in photo albums to be passed down from generation to generation, their silent stories admired by many.

Sources:

Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library has complied the images you see here as well as the full collection of Hugh Mangum’s work. You can find the collection here.

Sarah Stacke has taken on much of the task of researching and sharing Mangum’s work. She has been working with the Hugh Mangum Collection since 2010, and has curated exhibitions of and about his photos. Her work, ideas, and thoughts can be found here, and a full list of features can be found here.