“I came home and I left, again and again, each time reminded of the sadness and disappointment of my own upbringing, the terrible lack of stories.”

For Bea Chang, who contributed the memoir “The River My Father Promised” to our “Maps & Legends” print issue, life is — literally — a journey. At the time she wrote that essay, she had backpacked through fifty countries. The number’s even higher now.

”The River My Father Promised” was deemed a Notable in the 2017 Best American Essays series. We invite you now to float down a river — any river — with Bea and her softest travel companion.

The River My Father Promised

A quest through fifty countries.

1.

I didn’t grow up a river child; my father did. Around the same age that I began to learn how to ride a ten-speed bike, my father and my uncles and their friends were standing in a river with their pants rolled up, skipping rocks. They were river boys, he likes to say, and they grew up into mountain men. In college, they sneaked past anti-Communist guardposts by the pale gray of dawn to backpack into the mountain range that stretches down the heart of Taiwan.

I didn’t know any of this when I traveled all over Asia after college. It was my brother, not my father, who taught me how to skip rocks when I was ten because my parents kept their pasts tucked away, sealed off, like the unopened cardboard boxes in our basements. We had just packed up our lives in Taipei and moved to southern California, and my parents stayed in the air-conditioned hotel room while my brother and I stood with our toes soaking in a river. My brother walked me along its bank and told me to pick out a thinly sliced stone.

Why? I asked.

He replied, I’m going to show you some magic.

That first time I saw my brother skip a rock I didn’t believe what he was doing. I thought it was an illusion,like the card games with which he had deceived me so often. I believed that I knew the trick this time: he threw the stone hard enough that it hit the bottom of the river and it bounced up by sheer force. But when I tried it my stone dropped into the water with a pop — then it was quiet. My rock vanished.

My brother grinned. See? Magic. He tucked his tongue into the corner of his lips and chopped his arm through the air. You have to skim it on the surface, he said.

The path the stone carves out on the water, I noticed that afternoon, is unpredictable; it dances in a crooked, angular shape. You can never be entirely sure what path it will take — as soon as the stone falls, it becomes a shadow on your eyelids.

2.

My childhood seems fractured, sliced in half; it crumbled into fragile, uneven pieces. Even though we moved many times, so unpredictably, illogically, zigzagging our way around the globe, that first move was the butcher knife: It divided my life into the before and the after. It made my existence an impossible narrative, and the only way I could try to understand it was to pretend — so often that it began to become true — that I remember almost nothing of my childhood in Taiwan.

Except, of course, for the only story that my parents still tell about that time: I was a swimming champion. In the kindergarten division, I was the only one who didn’t use a tube. While the other boys and girls pedaled with duck-sized feet, I swam. Like a frog, my mother said, beaming about the way I glided through water, lapping everyone else. One morning, I won a blow-up dolphin. I tumbled with it in our living room, used it as a pillow when I watched TV. I tried to ride it in the pool, but my brother always flipped me over, so I pinched my nose and stayed under water until I ambushed him, tackling him as he tried to climb on. But when we moved to California, as with so many things, my mother deflated the dolphin and threw it away.

Within two years in the United States, I became scared of water. I stopped swimming. I forgot how to paddle, how to rip the water open with my arms. Instead, in our Spanish-style house that overlooked the Pacific, I would lie in bed thinking about tsunamis. I would pull the blanket over my face and shut my eyes and hold my breath, just to prepare myself for drowning. I would imagine water filling not only my lungs, but my stomach and my liver and my veins until my whole body became a puddle of water.

I thought about all of those thousands of screams, muffled in gurgling water until they were silenced, afloat and forgotten.

It must have begun when I was in seventh grade, when my brother told me about Atlantis. I thought about all of those thousands of screams, muffled in gurgling water until they were silenced, afloat and forgotten. I dreamed about the weightless tumble as my whole body flipped over and over in the powerful spin of the Pacific waves, the terror of not knowing which way the ocean floor was or where I could get a breath of air — just rolling and rolling and rolling.

Of course, I didn’t tell my parents this. And when I cried the night my father told us we were moving again, to New Jersey, he tried to appease me by telling me that a river ran through the woods in our backyard.

It worked, for a while. I thought of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, dipping my toes in its clear running water and reading a book on a polished rock, my chocolate Labrador lazing at my feet — how American of me.

As soon as we pulled into our new driveway, I ran to the backyard and through the woods. I couldn’t find it, the river my father promised. I ended up on my neighbor’s porch. Because what my father had called a river was a creek, if you could even call it that, a single stream of water that dried up before the week was over.

What my father had called a river was a creek, if you could even call it that, a single stream of water that dried up before the week was over.

We never talked about that river again. That was the way it was in New Jersey. Of course there were rivers — where we lived was peppered with lakes and rivers carved and left behind by the last ice sheet — but no one noticed them, hidden as they were, buried under the crisscrossing of roads and buildings.

I had to leave and come home again before I noticed the signs for Whippany River and Den Brook and Beaver Brook camouflaged in the bushes, too small, too concealed for drivers to take note.

Our high school, too, was situated on a tree-lined, winding road called Millbrook Avenue. It wasn’t until much, much later that I found out that a stream of water, Mill Brook, indeed ran somewhat beside it, that every day the river had followed me to school, watched my growing up.

For a moment, I could see Lenni Lenape children, centuries ago, walking along its banks, picking out sticks and skipping stones. But no one seemed to care….

Click here to jump to the full essay, specially formatted and illustrated for the web.

If you’d like to find out more about how Bea’s travel and writing and life fit together, find her interview in the Truth Teller Spotlight.

True stories. Honestly.

Images:

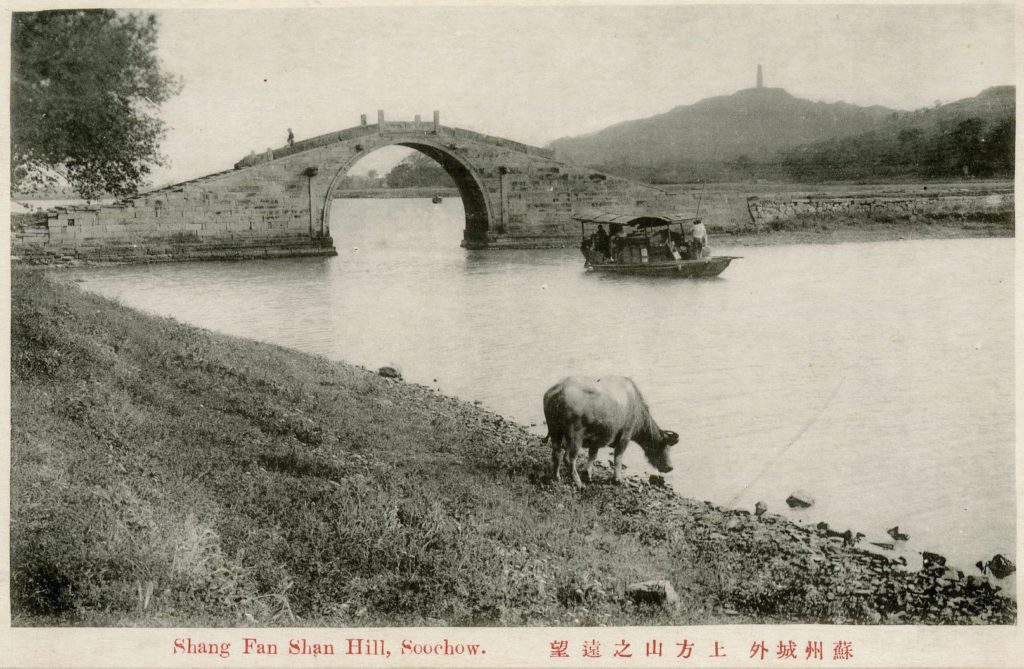

Postcard, Soochow River, c. 1890.

In a Far-Away Land, by Lee Strasburger. Watercolor.

Creek photo: sc.