Have you ever Googled your own name just to see what comes up? Of course you have — haven’t we all? It’s called “ego surfing,” but isn’t it also prudent to see what your online self is up to?

My name is unusual enough that typically the sites that come up actually do refer to me, or to Chris Gelineau, a young man from the Maine National Guard who died in Mosul during Operation Iraqi Freedom, or to Marie-Christine Gélineau, an OB-GYN in Canada.

But then came the day something new surfaced:

It takes you aback to discover such an opinion floating out there on the internet. Of course, I clicked on the link, to find to my horror that whoever had written that line had been right — at least as far as yet another Christine Gelineau was concerned.

The news report from the Concord Monitor in the New Hampshire capital gave every lurid detail: one Christine Gelineau and her “family friend” had spent weeks torturing her own eighteen-year-old son. The abuse detailed was indeed gruesome enough to warrant the headline’s verdict: Hellfire would be insufficient.

The Monitor’s story is no longer online, but plenty of others are. The story went viral, reaching Britain’s Daily Mail and The Huffington Post, among many other websites, print publications, and broadcasts.

Discovering such an evil Doppelgänger, I felt my own name turn to cinders in my mouth. And then there was the realization: Concord, New Hampshire, is ten minutes from where my daughter, my son-in-law, and my two little grandchildren make their home. How many nights would my daughter have heard the chipper voices of the local newscasters connecting her mother’s name to unspeakable acts — acts that this other Christine had committed against her own child? How many times would my daughter have viewed footage in which shocked neighbors offered the opinion that damnation would be inadequate for Christine Gelineau?

The damage that other woman has done to my good name would be the least of her crimes, but that damage is the lamprey eel that suctions onto me.

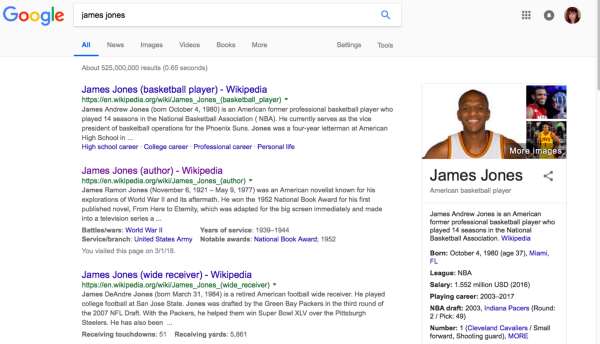

Of course I’m not the only one, or even the only writer, to suffer this curious sabotage. One James Jones was the author who gave us books like From Here to Eternity and The Thin Red Line. He died in 1977, the year before a different James Jones, the cult leader more commonly called Jim Jones, persuaded hundreds of people who had followed him to the jungles of Guyana to drink a blend of cyanide, Kool-Aid, and Flavor Aid. (Notice that Kool-Aid was only one of the flavorings used, but its name is the one besmirched by the pop-culture phrase “drink the Kool-Aid” — even brand names can become sullied through no fault of their own.)

James Jones the Author never heard those horrific news reports, but even before I learned of the dark Other with my name, it had occurred to me to wonder what it must have been like for my friend Kaylie Jones (an author in her own right) to have been barraged day after day with Jim Jones, Jim Jones, cyanide, swollen corpses, dead children. Still a teenager when this happened, and understandably protective of the reputation and legacy of the father she had so recently lost, Kaylie knew the horrific events in Guyana had nothing to do with her father. At the same time, she surely couldn’t help but feel infuriated that someone unworthy of any connection to her dad was contaminating her father’s name.

At least James Jones has the benefit of a degree of ubiquity — it’s the kind of name you have already become accustomed to sharing, a name that, as you build your identity, you think of as only one marker of what makes you you, and not necessarily the most distinctive one.

But if your name is Andrea Yates, Charles Manson, or Jeffrey Dahmer, don’t you hesitate to say, “Hi, I’m . . .” when you meet someone new? Don’t you watch for a hand that had been extending but that drops back, slides into a pocket at the sound of what to you is still your good name?

It took me months finally to ask my daughter what she had heard. How do you bring this up? It felt too incendiary for text or email, and given the ages of her children, my grandchildren, our phone calls ran to Facetime with the kids.

No one was going to drop this into a conversation that involved a seven-year-old and a four-year-old. I didn’t want to dignify this indignity with the importance of, “Hi, are the kids in bed now? I just called to ask if you heard about . . .”

At least I tell myself now that was my motivation. It’s hard to characterize what I was feeling. Much as a writer’s life might revolve around words, it was exceedingly hard to find the words, the tone, the timing to ask your daughter what she’s heard about the torturer with her mother’s name.

It was close to a year after the Concord woman’s arrest, on a visit to New Hampshire, when I finally found myself in the car with just my daughter.

“What?!”

It was a relief to hear her incredulity and surprise. She had not heard a word about the stranger with my name. The sickening news reports had spread internationally, but ten minutes down the road, my daughter had known nothing about it. That much was a gift.

But, of course, the internet is eternal. The dark story still lurks out there, waiting to be found by my aunt, my cousins, my grandchildren, or (in some ways even worse) people who know only me — and only in passing.

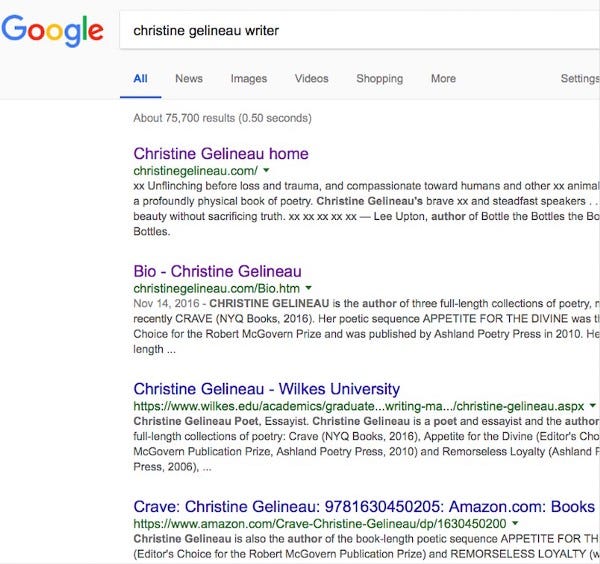

You know you’re going to do it now: rush to your device to look up just exactly what this Christine Gelineau did. I accept the inevitability of that much, but can you do me a favor? When you’re through vomiting over what she did, please go back and click on two or three of the sites that actually are about me, not her. She is now in jail, where she belongs, and I have finally gotten things to where she no longer comes up first in the feed — most of the time.

I would dearly appreciate your help keeping it that way.

********************************************************************************************************

Christine Gelineau has won numerous awards for her poetry and prose, including a Pushcart Prize. She is the author of three full-length collections of poetry, most recently Crave (NYQ Books, 2016). Her poetic sequence Appetite for the Divine was the Editor’s Choice for the Robert McGovern Prize and was published by Ashland Poetry Press in 2010. Her first full-length collection, Remorseless Loyalty, won the Richard Snyder Prize, also from Ashland Poetry Press (2006). She is also the author of two chapbooks from FootHills Publishing: North American Song Line (2001) and In the Greenwood World (2006). With Jack B. Bedell, she edited French Connections: A Gathering of French-American Poets (Louisiana Literature Press, 2007). Her poetry, essays and reviews have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, including NY Times Opinionator, Prairie Schooner, New Letters, Connecticut Review, The New York Quarterly, The Iron Horse Review, Green Mountains Review, Georgia Review, American Literary Review, Seneca Review, Louisiana Literature, The Paterson Literary Review, Sentence: A Journal of Prose Poetics, The Beloit Poetry Journal, The Florida Review, and others. Her poem “Accident” was published in Broad Street, both in print and online (click here to read it).

Christine Gelineau has won numerous awards for her poetry and prose, including a Pushcart Prize. She is the author of three full-length collections of poetry, most recently Crave (NYQ Books, 2016). Her poetic sequence Appetite for the Divine was the Editor’s Choice for the Robert McGovern Prize and was published by Ashland Poetry Press in 2010. Her first full-length collection, Remorseless Loyalty, won the Richard Snyder Prize, also from Ashland Poetry Press (2006). She is also the author of two chapbooks from FootHills Publishing: North American Song Line (2001) and In the Greenwood World (2006). With Jack B. Bedell, she edited French Connections: A Gathering of French-American Poets (Louisiana Literature Press, 2007). Her poetry, essays and reviews have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, including NY Times Opinionator, Prairie Schooner, New Letters, Connecticut Review, The New York Quarterly, The Iron Horse Review, Green Mountains Review, Georgia Review, American Literary Review, Seneca Review, Louisiana Literature, The Paterson Literary Review, Sentence: A Journal of Prose Poetics, The Beloit Poetry Journal, The Florida Review, and others. Her poem “Accident” was published in Broad Street, both in print and online (click here to read it).********************************************************************************************************

Like what you’ve read here? Then please follow Broad Street on Facebook and our website.