“Your body is not a thank-you note, my mother wrote to me in a card …”

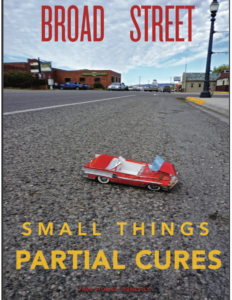

BROAD STREET presents a feature from our summer 2018 print and iBook issue, “Small Things, Partial Cures”: Writer Valley Haggard catalogues her body, and artists Mary Chiaramonte and Susan Singer capture it in paint. Read on for Valley’s reactions to the posing process and the final paintings.

This feature is also available, in slightly different format, on Medium. Order a print copy of the whole issue through Submittable here (go to the bottom of the page). Get the iBook here.

Valley’s Folds, by Susan Singer.

Valley’s Folds, by Susan Singer. The Body, in Parts

An invitation.

Breasts

My breasts are planets, stars, meteors, heavenly bodies. They are wrecking balls, bulldogs, fully inflated birthday balloons. My nipples had no feeling until I gave birth to my son, and with all that sucking and mewing and grappling he gave them the life that they in turn gave him. My breasts defy Victoria’s Secret, beg for an engineer, need structural, architectural support, blueprints, infrastructure, hard bites, and kisses.

In high school a friend and I turned the lights off and weighed our breasts on her mother’s bathroom scale. Naturally her mother walked in, turned the lights on, asked if we were lesbians. Were we? It was not an either/or question, as I would later discover. Now, we were scientists in search of evidence, detectives in search of a clue.

Skin

My mother told me that if you connected my birthmarks from head to toe you’d get a map of the constellations, and that the big one between the small of my back and tailbone was where the angels kissed me. Maybe that’s why I have never wanted a tattoo. I was born with a map of my skin, my very own connect-the-dots.

Thighs

My thighs are strong and jiggly and burn their way up stairs and down mountains, through squats and lunges and rolling hills. They wrap around backs like bows around a present. They are liquid rumbling. Would a volcano apologize? Would an earthquake promise to occupy less space?

Right Hip

Every story I haven’t written or am currently afraid to write is compressed into my right hip. The massage therapist presses her thumb into the acute horror of my life and it vanishes without being adequately expressed, right there in that hinge in the center of me. I’d been told I had child-bearing hips, but I didn’t know they would bear so many of my stories, too.

Feet

My father had such big feet that when he was a little boy people said he looked like the capital letter L. My mother planted seeds in her last pair of high heels, planters now for new life on her front porch. My mother and I have inverse bodies. I’m big where she’s small and vice versa. It’s like she cut out her own negative space and used it to make me. My father is a planet all his own.

On my wedding day, I went barefoot. Tiny splinters stabbed through the flesh between my heels and toes. On that king-sized bed in the hotel where I spent my first night newly cleaved to the man who was now my husband, their extraction caused far more curiosity than pain.

Hands

My father told me he’d buy me a car when my hands got as big as his, and for that I am still waiting. My mother’s hands were always stained with oil paint, clay, dirt; she rarely wore rings or polish.

Agreeing to wear the same platinum bands on one hand for the rest of my life was bigger than spoken vows.

My hands have kept and broken promises.

Old Love, Like Light, by Mary Chiaramonte.

Eyes

At birth my eyes were gunmetal blue according to my mother, but my best friend in elementary school said they were the color of cement. My mother’s and father’s and husband’s eyes are brown holes dug out of the center of the earth, while in my blue/green/gray I have often felt like a cat lost far out at sea.

Hunger

The only thing I’ve ever truly understood about my body was what I wanted to put inside of it. Pink wine sweeter than Kool-Aid, coils of black smoke, liquid fire, the creamy bite of strong coffee, enough food to at last feel secure, safe, sated. I don’t know how hunger works but I know how I want my body to feel when I’m willing to feel it at all: like an animal that has found a home in this loose casing of skin.

Belly

A thirteen-inch scar zig-zags down the side to a cut above the pubic bone: soft pink jagged lines where the skin was cut, sewed, and stapled. Bled.

The steps up to our bed, which my husband built, the bandages he changed, the wounds he cleaned, the days and weeks in the gauzy filmy haze of the hospital, the tumors, the unborn. The parts of me removed and then sent to Pathology: a uterus, a gallbladder, an adrenal gland, a rib, all those unborn babies.

A Thank-You Note

Your body is not a thank-you note, my mother wrote to me in a card when I was in Alaska, half in love with the captain of the fleet, half in love with the deaf deckhand teaching me American Sign. Half dead, half drunk, half sober, half crazy.

Oh, but it was. It had been. It has also been my passport, my license, my excuse, and getaway car before it became a grave, a temple, a tombstone. My body has been a deadweight lump of unformed clay that I’ve kneaded and rolled and tried to shape, full of hidden treasure I’ve been desperate to find and spend. I’ve thrown it at strangers, hidden it from my husband, given it like a shield of flesh, an orchard of sustenance, a playground to my son.

Hair

A meteorological disturbance beyond my control or command, my hair answers to no one. My husband too has unruly thick black hair, hair that precedes him into a room. Our son has blond hair with specks of gold and red and orange and I try to decode him one strand at a time.

Invitation

Sit on my lap, feast on me. My body is not a thank-you note but it has been an invitation. Yes, I feel like Mother Earth. Yes, I feel like Eve. I want to form and grow and then eat the apple.

The body is, in parts, digestible like an apple. An elbow, a pinkie, a knee. Add the whole thing up and you have a universe lumbering around, trying to change and break and make the world with sex and death and babies.

It is a beautiful mystery to be a woman. We get the opportunity every single day to learn how to love ourselves the way we might learn to love the universe at the beginning of time. Life has started and ended in my womb and now my womb is gone and yet my body is still magic, a magician who has lost her hat but memorized her spells. I sit and walk and kneel and do normal human things, but don’t all the gods, isn’t that part of their charm?

My body is not a thank-you note but it is a prayer, a song, a mourner’s kaddish, an announcement of miraculous birth.

*****************************************************************************

Entering the World: Valley writes about the Artworks

Old Love, Like Light. What writer doesn’t dream of entering the world of fairy tale, transforming into myth? Mary Chiaramonte’s paintings are so lyrical and haunting and rich with narrative that I fell in love with her entire body of work instantly. To be painted by Mary was to see myself in a way I’ve always longed to be seen — as a character within a story, within one of those favorite fairy tales or myths. I’m pretty sure the version of me Mary captured has visited more realms than one, has multiple superpowers, and is close friends to a host of nymphs, beasts, and magical creatures. Mary gave me a version of me I long to be.

************************************************************************************

The Contributors

Valley Haggard is the author of The Halfway House for Writers and Surrender Your Weapons, and she co-edited Nine Lives: a Life in 10 Minutes Anthology. She has also published numerous essays, stories, and reviews. She founded the online literary magazine Life in 10 Minutesand a year-round creative writing program, Richmond Young Writers. Read more about Valley and her approach to telling the truth–and get a few boosts for your own memoirs–in her Spotlight Interview here.

Valley’s photograph is also by Mary Chiaramonte.

Mary Chiaramonte’s narrative oil paintings have been featured in exhibitions throughout the U.S. She is the recipient of multiple honors for visual arts, including 2018’s Art Renewal Center publication award.

Susan Singer’s primary focus as an artist and writer is on beauty, whether it be of the body, the soul, the landscape, or the human condition. Valley’s Folds is from Beyond Barbie, a series of over fifty life-sized nudes of all sizes, shapes, ages, and races. Her work has been shown around the world, most recently in the Akureyri Art Museum in Akureyri, Iceland.

Order a print copy of this issue through Submittable here. Order the iBook here.

*********************************************************************************************************

Like what you’ve read here? Then please visit us at BroadStreetOnline.org to order a print or iBook copy or just to poke around and see what else we have on offer. And please follow us on Facebook!

True stories, honestly.