At BROAD STREET, we celebrate each word we publish. Choosing nominees during awards season is never easy, but here are six outstanding pieces from 2018 — with thanks to everyone who has helped us bring great true stories to the world this year.

You can sample the works (and even buy a copy) below.

This year’s nominees are …

Walter Cummins, “Commitment”: on consigning a wife to others’ care. Memoir-essay, available in full online here.

Kathleen de Azevedo, “Broken Wings of Paradise”: on disability in Brazil’s land of the body beautiful. Memoir-essay.

Peter Grandbois, “Pain.” Memoir.

Donovan McAbee, “What to Do with What We Are Given.” Poem.

Amy Sailer, “Litany of Missing Earrings.” Poem.

Sara Talpos, “To Fill a Room with ‘Nobody,’” an essay on Emily Dickinson and mitochondria by a poet and science writer.

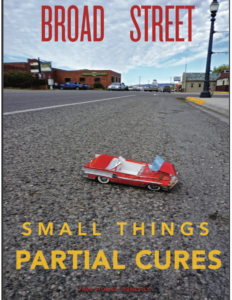

These pieces are from our summer 2018 “Small Things, Partial Cures” issue. To buy your copy through iBooks, click here. To buy a print issue (which can be processed online through Submittable or via a check in regular mail), go here.

***************************************************************************

And now for a few words from the nominees:

PETER GRANDBOIS, “Pain”: Your twenties are your prime fencing years. Each day you count the yellow bruises and red welts on your chest in the mirror. Sometimes you catch yourself pressing on them while in class or at work just to feel the sharp sting all the way through the bone, as if the pain carried more with it, and if you just kept poking at it, prodding it, you might find the answer to who you really are.

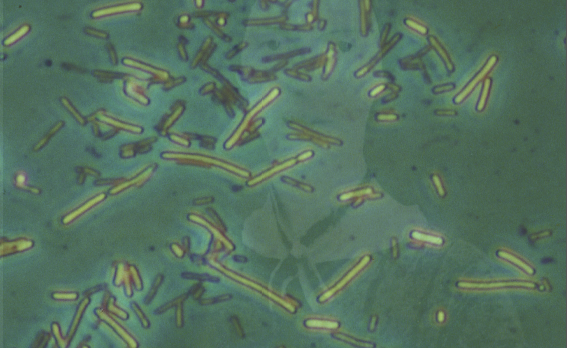

SARA TALPOS, “To Fill a Room with ‘Nobody’”: The bacteria, stained pink and magnified 2,000 times, looked like tiny pill capsules scattered across the slide. If I could line them up lengthwise — 18,000 of them — they would stretch as far as the first line in Emily Dickinson’s poem “Estranged from Beauty.” […] This movement of DNA across membranes reminds me of poetic enjambment: how a sentence or a thought is carried across a boundary — the poetic line — without punctuation to stop it.

Image by Josef Reischig.

AMY SAILER, “Litany of Missing Earrings”:

WALTER CUMMINS, “Commitment”: What would I find that afternoon when I drove home from that parking lot, eyes fogged, the road a blur, navigating from memory? Inevitably, a gaunt woman with fixed dark eyes and a tangle of wiry dark hair sitting rigid in a chair, engulfed by smoke, a cigarette squeezed between yellowed fingers. Her jaw would be clenched, but not tightly enough to stop the grinding or silence the endless mutterings of voices, the torment that had taken over her awareness of the actual. She wouldn’t react to my entry, the shutting of the front door, because she didn’t see, didn’t hear, didn’t care.

KATHLEEN DE AZEVEDO, “Broken Wings of Paradise”: The farther north one travels in Brazil, the harder life is, and the more visible the afflictions. There is not much in the way of “mobility devices” to hide the real difficulty of not being able to walk. The subway in Recife, for example, starts downtown, passes through a series of poor communities, and ends at the main bus depot. All along these stops, friends and family members bring disabled persons (some of whom are carried on the backs of the ablebodied) and place them in the cars in order to beg. The beggars drag their limp legs up and down the aisles, placing their hands on the knees of passengers and asking for money. These beggars force us to stare, and to consider the discrepancies in not only economic privilege but the privilege to move freely. They also create an ethical dilemma: If I look at their obvious disability, is this an insult? If I look away, am I being insensitive? If I give money, is that a futile drop in the bucket? When I say I have run out of change, do they believe me?

DONOVAN McABEE, “What to Do with What We Are Given”:

“The only real pain is your own.” — Peter Grandbois