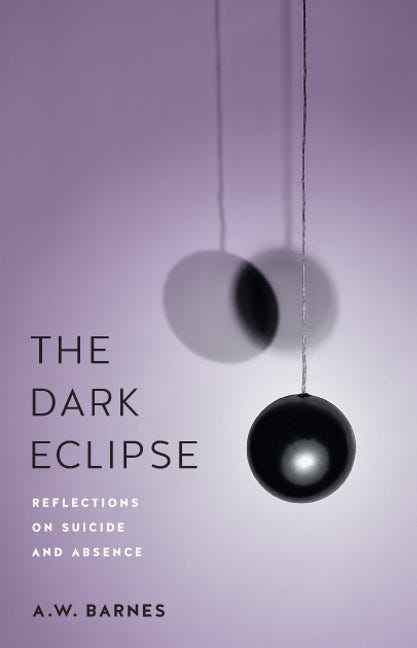

Andrew (A. W.) Barnes’s book of essays, The Dark Eclipse: Reflections on Suicide and Absence, debuts with Bucknell University Press on December 14, 2018. It includes “Familial Bodies,” published in Broad Street’s online iteration.

The publisher describes The Dark Eclipse as “personal essays in which A. W. Barnes seeks to come to terms with the suicide of his older brother Mike. Using source documentation — police report, autopsy, suicide note, and death certificate — the essays explore Barnes’s relationship with Mike and their status as gay brothers raised in a large conservative family in the Midwest. In addition, the narrative traces the brothers’ difficult relationship with their father, a man who once studied to be a Trappist monk before marrying and fathering eight children. Because of their shared sexual orientation, Andrew hoped he and Mike would be close, but their relationship was as fraught as the author’s relationship with his other brothers and father. While the rest of the family seems to have forgotten about Mike, who died in 1993, Barnes has not been able to let him go. This book is his attempt to do so.”

We interviewed Andrew by email on the eve of the book’s publication.

***********************************************************************************

Broad Street: Here’s a question we ask everyone — a question that becomes ever more poignantly important with each passing day: How do you define truth, and how do you make sure that your writing is truthful?

Andrew: As a memoirist, I am most interested in emotional truth. Yes, we have an obligation to be true to the facts of the stories we tell in our memoirs and personal essays — we cannot invent stories or scenes that simply did not take place unless we set up those scenes as fantasy or wishful thinking — but we can use narrative tropes to capture the emotional truth of a scene. That is, we can collapse time in order to make relevant scenes happen closer together in order to highlight their connections; or, we can imagine dialogue between characters that truthfully capture the nature of those relationships.

We also have to recognize that memory is a terrible recorder of truth. But it is our responsibility to be truthful to our memories — those truths are formed by our experiences, which in turn have created the people we are — even if those memories are in conflict with the memories of other people who may have experienced the same events.

Congratulations on publishing your book of essays, which includes the piece we published about your brother’s suicide and your troubled relationship with your father. Could you trace the genealogy of this project, from first germ of idea through the years (presumably) of writing the essays, finally with publishing the book?

My brother died twenty-five years ago, and it has taken me over twenty years to write this story. I have written many different versions of it in books and essays that never saw the light of day. In order to write this book and see it through publication, I needed distance and time to see it clearly.

The book is a series of essays that read as a memoir. Each essay is centered on a document that concerns my brother — his death certificate, the autopsy report, the police report, etc. This idea to write this book using these documents came from from two different people: my mentor, Susan Cheever, and my therapist. One day, Susan had said in passing that she was waiting for someone to write a memoir based on their driver’s license. I was very intrigued by this idea, although I don’t know what a memoir based on a driver’s license would look like. However, that conversation planted the seed to look at the documents that surrounded Mike’s life and death.

Second, years ago my therapist asked me questions about Mike’s death: Where did he die? How did he die? Who found him? What was the poison he used to kill himself? I didn’t know the answer to any of these questions, and when he asked me why I didn’t know, I didn’t have a good answer.

So I began gathering the official documents that detailed his death. In this way, I was able to lay the groundwork of this book on indisputable facts in order to attempt to get at the truth of why Mike died, even if in the end I cannot know with absolute certainty.

We have to ask — but you don’t have to answer — how is your relationship with your father and the rest of your family now? Has publishing your memoirs affected those relationships? How so?

I have a distant relationship with my family — except for my mother, with whom I’m in regular contact. For my family, having children and raising them in our hometown of Indianapolis has been the ultimate calling in life. Any other kind of life is view as “less-than.” Because Mike and I were/are gay, and because we chose not to have children and raise families, and because we left Indianapolis and established ourselves on the East Coast, we were viewed as “less-than.”

To the rest of my siblings, our lives are not as valuable as the lives of people who are married and have children. I am on speaking terms with them, and visit them occasionally, but the emotional connection that ties families together is simply not there.

My relationship with my father has always been fraught. My father is eighty-nine years old now, and he has COPD. He’s in the last years of his life. My current book project — titled My Father’s Body — is an attempt to reconcile with my father, not by trying to get him to accept responsibility for the way Mike and I were raised, or to acknowledge his part in Mike’s death, but rather by trying to accept those parts of me that resemble my father or that I inherited from father.

I have the same body shape as my father. I have the same face, the same bald head. I have some of his traits: his stubbornness, his moral rectitude, his inability to forge lasting friendships — even though these traits in me are less sharp than they are in him. I have a very difficult time looking in mirrors because when I do I see my father. I chide myself for being stubborn when I should be more open, for being too judgmental when I should be more accepting, for pushing away friends when I should draw them closer. In this new book, I am trying to come to terms with the parts of me that I inherited from my father in order to forgive him.

We sincerely hope that happens. Thank you for the interview, and congratulations again on the book!