“ Somewhere in the Universe a molecule shifts, and here on Earth, these telescopes perk up. Oh, oh: who’s there?”

–

Another Planet of Its Own

The astral is the personal. A feature from our Winter/Spring 2019 “Rivals & Players” issue.

By Katharine Haake

–

Dreamscape

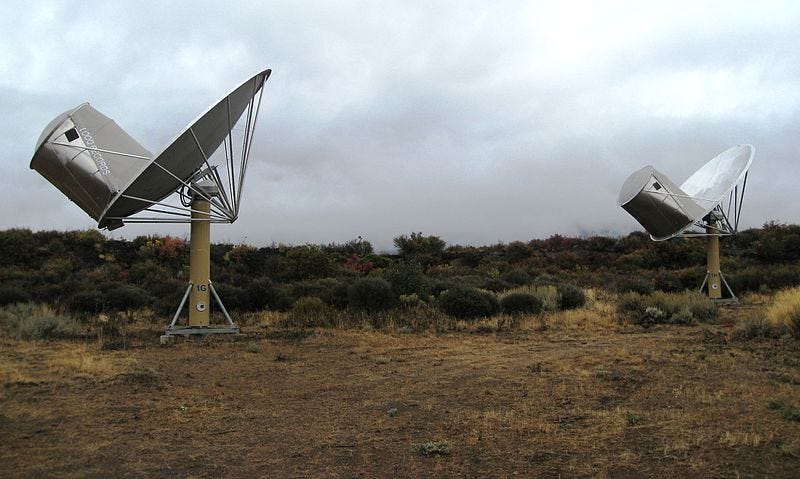

Not long ago, I hiked the summit trail of Lassen Peak in the Shasta Cascade mountains of northern California and found myself surveying a sobering dominion of rock and sky. This being a hike I’d done often as a girl, but not for many years, the trail had given me a feeling a bit like déjà vu, but not quite: simultaneously familiar and strange. Now, from the peak, I had the same sensation: every bit as if I’d seen all this a thousand times already and yet never once before. There was a sense of a dreamscape to the panoramic views all around me. To the west, a few nameless jagged peaks, then lower — much lower — the far north end of the Sacramento Valley, my childhood home. To the east, a bare flank of igneous rock sloped all the way down to a vast lava field where I could just make out a cluster of tiny white spots that looked exactly like what I knew them to be — small white ears perked up and listening for signs of intelligent life high above and unimaginably far away.

From the top of the mountain, if you know just where to look, you can barely make them out — little white beads against the blackened ground of the lava beds below. But closer up, their twenty-foot diameters are modestly proportioned to a comfortable human scale. Shrouded by graceful white orbs that arc like protective wings behind them, these diminutive radio telescopes can pivot and turn to the slightest atmospheric shift or molecular deviations a thousand light years away.

I will say that again: somewhere in the Universe a molecule shifts, and here on Earth, these telescopes perk up. Oh, oh: who’s there?

These are the radio telescopes of the SETI Institute’s ATA at SRI International’s HCRO.

By SETI, I mean Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence, the Institute, a nonprofit corporation which, since 1984, has been dedicated to the ongoing study of life in the universe somewhere beyond planet Earth.

By HCRO, I mean the Hat Creek Radio Observatory, once a University of California at Berkeley installation, now managed by SRI International.

By SRI International, I mean a private, nonprofit organization, once the Stanford Research Institute, that formally separated from Stanford University in 1970 and that, since 1977, has been known as SRI International.

By ATA, I mean the Allen Telescope Array, so named for benefactor Paul G. Allen, whose other notable achievements include the 1975 co-founding of Microsoft with Bill Gates and multiple philanthropic endeavors in support of education, the environment, and the arts. Located at the HCRO, just northeast of Lassen and some three hundred miles northeast of San Francisco, the ATA was completed in 2007 and, except for a brief hiatus in 2011, has been listening to and studying noise from the universe ever since.

The ATA is an LNSD, by which I mean a Large Number of Small Dishes array of telescopes where many small dishes working together take over functions once served by larger instruments. They’re cheaper to build and more flexible that way. You can move them around and add and subtract, kind of like a mix-and-match wardrobe. The future’s ever open-ended with an LSND. In this case, at the ATA, there are currently 42 of them, all focused outward on space, either on the same point or on different areas, each listening, listening — listening.

I didn’t know this at the time, but once before, I had an odd connection to the SRI. When I was at Stanford studying writing in the early 1970s, I lived in a big house on a leafy street in old Palo Alto, shared with an assortment of roommates I barely remember who were all a bit older than I was, young men and women no longer in school but still just starting out on the paths that would take them into the rest of their lives. Among them, there was a jocular bearded biologist with whom I shared a deep love of nature, a moody dark-haired something of ambiguous gender identity, an eccentric unemployed woman subsisting on what she called a “trust fund” and what my other roommates called “welfare for the totally mentally disabled,” and a jittery thirty-something researcher for the SRI. He called himself a futurist and came home spouting theories that seemed truly mentally disabled to me — heady visions of a future where computers ran the world and where we’d all be hooked together by small devices in our ears, fevered fantasies of sentient life in outer space.

How I Know

Not that I’m an expert on any of this. You, too, can find these acronyms (there are a lot of them when you get into questions of space research) on the internet, a system once fantastically prophesied by my former roommate. The internet is also known as the WWW, or the World Wide Web.

Much of what I’m telling you I know by chance and happenstance, by virtue of where my family settled and who my sister knew. All four of my grandparents met and married as medical personnel in a small mining town now inundated behind Shasta Dam some seventy miles west of Hat Creek. On May 22, 1915, they sat on their porch to watch as Mount Lassen erupted in a devastating volcanic blast that rained ash more than two hundred miles to the east. Coincidentally, some seventy-five years after that, on May 18, 1980, I sat in an attic apartment in Missoula, Montana, and watched as ash blew in from the eruption of Mount Saint Helens, nearly 200 miles to the west.

I think about that now — my ash, their ash, how I came to grow up in the shadow of both mountain and dam, my unlikely connection to Hat Creek established through my sister’s best friend’s husband, who worked as the observatory’s resident astronomer for more than twenty years. A job like that looks pretty good to those of us who think it would be neat to spend our lives in the mountains far away from everything, but in fact, it turns out to be kind of a mixed bag. Brainy Ph.D.’s themselves with complex research interests and keen engineering instincts of their own, resident astronomers do, in fact, get to live onsite in a wilderness of rock and star, but since their first obligation is to keep things running smoothly, their allocated telescope time is generally limited to a space-available basis.

My sister’s best friend’s husband didn’t start out looking for life in outer space. He started out, like many of us, with big ideas and curiosities vis-à-vis the mysteries of the Universe, which did not yet include communications beamed down at us from distant galaxies. Before the ATA, Hat Creek was a conventional radio dish observatory founded in 1958 by UC Berkeley, with its first two big telescopes, completed in 1962, measuring individually 33 and 85 feet in diameter. By 1987, which would have been about the time my sister’s best friend moved there with her husband, these original dishes had expanded to become the Berkeley-Illinois-Maryland Array — also known as BIMA — jointly operated by UC Berkeley, the University of Illinois, and the University of Maryland and, at one time, the world’s premier imaging instrument at millimeter wavelengths. And then it was gone, moved, at least in part, to make room for the ATA.

But none of this says what I really mean to say, which is that up there, on the other side of the northeast flank of Lassen, there’s an immense expanse of lava beds — a chaotic jumble of rocks, scorched earth, underground tubes, and bottomless holes — that is just about as desolate, as far out of this world as you can get and still be in California. This suited my sister’s best friend and her husband just fine, and it suited SETI too: if an alien landed there, he might feel right at home.

Just as we build optical telescopes in remote places to avoid spectral interference from artificial light, we set up radio telescopes far away from the noise of human life. But the lava beds at Hat Creek, I don’t know — are they a kind of bonus? Does their rockiness function as a natural sound sink? Does it draw whatever messages may be drifting out there into it, every bit as if it were another planet of its own? Inhospitable, remote, the beds also keep people away, and save for the small number of scientists in their research enclave, the few people who make their homes nearby do so for precisely the same reason the HCRO was founded there to begin with: no interference.

The early years of this new millennium were a generally hopeful time in our search for intelligent extraterrestrial life, and the ATA, in 2007, was forward-looking and ambitious. In development for more than a decade, plans called for an eventual total of 350 telescopes, although to date, the array continues to operate with the original 42. It’s big but was going to be bigger — the biggest in the world — and who knows, maybe one day it still will be. Maybe someday far from now, in phase two or three or ten and a still-inconceivable future when we won’t even need little things in our ears to share our thoughts with others, the ATA will have expanded beyond our current expectations and be abuzz with real-time ET transmissions from as-yet undiscovered species who will be revealing to us, then, precisely how and where we’re going wrong now.

By ET, I mean extra-terrestrial, but probably everyone already knows that.

Even with just the 42 telescopes, the ATA is a cutting-edge installation capable of producing a complex system of simultaneous surveys undertaken at centimeter-long wavelengths and spanning four and a half octaves of frequency. It’s really quite beautiful in concept, a vast and intricate web of electronic sensors tuned to the heavens in a great woven net or earthly mantle, a dream-catcher of infinite dimensions.

You should know I don’t use the word infinite lightly.

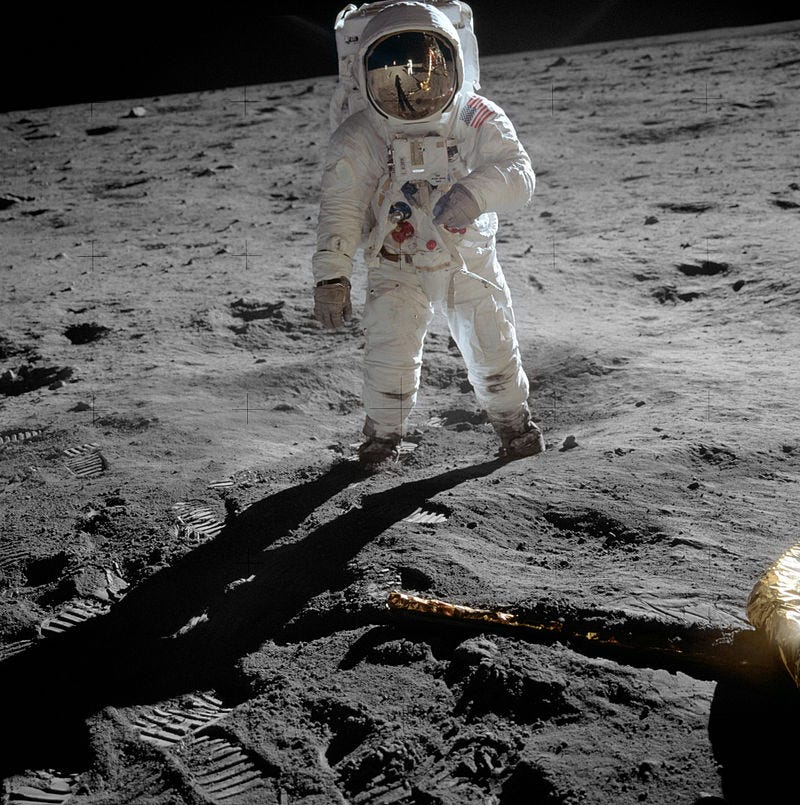

On July 20, 1969, the first American man, Neil Armstrong, walked on the moon. I was an adolescent then, a more or less new human being starting out on the planet, and well remember the unspeakable thrill with which this first celestial encounter sent me running out into the summer night to stare up at the moon in a near-euphoric state of what I now call wonder. How vividly I remember that moon as round and full and bright — but the internet tells me I am wrong, that it was in a waxing crescent phase, a tiny sliver.

After Armstrong, there were more — a second, a fourth (they went out in pairs) — all together, twelve American moon-walking men, one for each month of our lunar year.

Six of them drove moon rovers on it. Then they left them behind, three improbably abandoned vehicles looking for all the world more like the Erector Set fancies of a precocious child and his toy than the space-age marvels they are, up there still waiting for someone to come back and take them out for a spin. Unless someone does something to move them, they’ll wait for a million years, maybe two, right alongside the tracks they have made, the footprints of the men who walked beside them.

Meantime, back on Earth, eight of our moonwalkers have since died.

How natural all this seemed to us then. Not the dying — still so far in the future as to be unimaginable — but the great bounding leaps with which they cavorted about on our luminous moon.

Naturally, we want this to be true. We remember it that way, ebullient men at play in a gravitational field a mere sixth of that on Earth, their sober and intrepid explorations interspersed with soaring jetés of joy. But mostly, they plodded. The moon was there, and they were on it, the soles of their boots firmly anchored with something like lead.

These days, where I live is up an L.A. canyon in a small midcentury house with a back wall of glass that looks out on a scrubby hillside of the Santa Monica Mountains. Other broad windows open over the canyon itself and flood, some nights, with the rising moon: the very moon where, over time, twelve Americans walked, a full jury’s worth.

And that’s pretty much astronomy to me.

Not Some Wild and Crazy Stargazing Nut

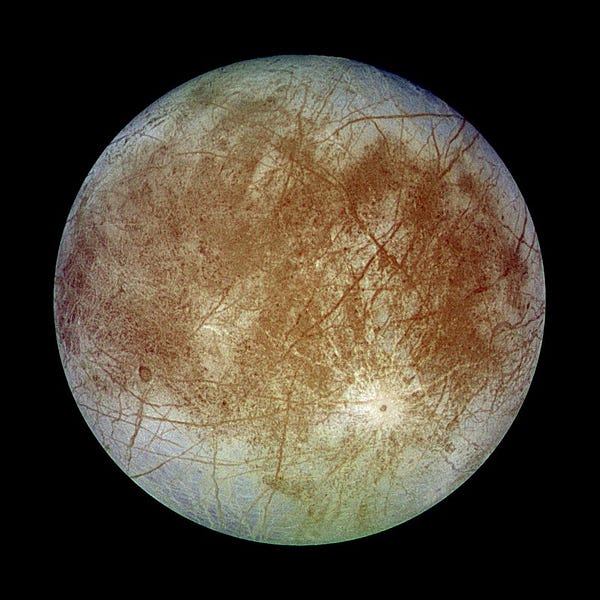

So no, I’m not some wild and crazy stargazing nut. When it comes to the heavens, I know where to draw the line. I didn’t drive to Idaho or Oregon to watch the last solar eclipse. I’ve never owned a telescope and won’t stay up past midnight or awaken before dawn to ogle at other big cosmic events — a Super Blood Moon or transit of Venus, a Perseid meteor shower. I’m interested, but not fanatical. Still, I’ll marvel, like anyone, at NASA’s latest photos on the front page of the New York Times or occasionally check in on the progress of a Voyager or Rover. And what happened to the spacecraft Galileo broke my heart.

You must remember that: how after fourteen years in space, it was decommissioned to protect one of its own discoveries — a potential ocean beneath the ice crust of the Jovian moon Europa. This was in 2003. My two sons had been babies when that spacecraft launched; the older, already in college when it came to its fiery end. People say it self-destructed, but it would be more accurate to say that astrophysicists on Earth — some 600,000,000 miles away — directed it to self-destruct, beaming up some new computer code to terminate its scientific mission and send it straight into the clouds of Jupiter at incineration speeds. Just poof, no more Galileo.

You just can’t go scattering terrestrial microbes into the Universe like that. Of course not. Who knows what might happen, what new species we might breed, who might be speaking to us some 4,000,000,000 years from now?

But we didn’t think like that in 1989. We were just starting out. These days, we’re more careful and launch our probes aseptic. That way, if we find another ocean somewhere, we can check it out.

***

I once met a man who discovered a star that now bore his name. This was when I was in college at UC Santa Cruz. I was a bit of a loner and didn’t talk to others much, but I did like to sit out by myself and sunbathe — when there was sun — to soak up some rays and get what we used to call “color” before we knew it was bad for our skin and might give us cancer.

So maybe that’s how it happened — me in the sun somewhat skimpily clothed — that this man was inspired to approach me and start a conversation that began with his star and quickly moved on to a not-so-subtle invitation for me to come to Berkeley so he could take me to his lab and show me his star, along with other wonders of the Universe. The star was exotic, and so I was tempted, but I never went to see him, because I was shy and also because, back then, such visitations were all about sex.

In yet another, more recent stellar highlight of my life, I was out hiking with a friend in the nearby Sierra Pelona Mountains of northern Los Angeles County when we came off the Vasquez Rocks trail and ran across a group of citizen astronomers setting up with their equipment in the parking lot for the night. Something big was about to happen — I don’t know, a comet, some rare planetary alignment? — and a fair-sized crowd had come out to ogle, all milling about with their cameras and beer. People seemed eager to show off their stargazing apparatus, so we hung around for a while, admiring a wide assortment of instruments that pretty much ran the gamut from hefty scientific-grade telescopes to homemade peep-hole devices. Everyone was nice and maybe already a little buzzed (there was plenty of beer), pumped up from whatever event was coming in the night. But it was summer, still light in the late afternoon, and there wasn’t much we could see, they said, until the sun went down and the stars came out.

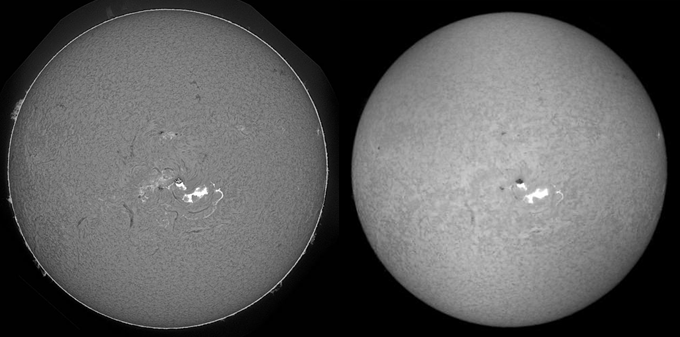

One man, though, had a solar telescope, and he let us look at the sun.

At least he said it was the sun, but it didn’t really look like what you’d think the sun would look like if you could actually look at it, which for that once, we could. The sun is a star — a pure source of heavenly light — and what we saw … I don’t know. It wasn’t luminous at all, but rather dark and massive, with something deep and threatening about it, a great roiling mass of molten brown and gray spotted with clusters of flickering black … somethings.We stood there for a while, taking turns at the telescope and uttering little sounds of amazement, while, behind us, the man went on as if speaking to the dimmest of children about how the sun just seemed like that because you had to use a filter to look at it at all. He said we should be able to spot solar flares — did we see them?

Of course we saw them. They were the somethings.

It was a strange feeling, looking at the one thing in the world (or out of it, I guess) you knew you were not supposed to look at on pain of going blind, or crazy, or burning a hole through your brain.

What Went Down in Roswell

Other big telescopes I’ve been to include those at the Griffith Observatory in L.A.; the Palomar, near San Diego; and the Hobby-Eberly at the University of Texas’s McDonald Observatory in the rolling Davis Mountains of West Texas. Among them, this last one — also known as the HET — was a more or less accidental sighting, just a roadside stop on a summer road trip — half odyssey, half lark — with a lifelong friend and sometime traveling companion, a woman so much more adventuresome than I that, between us, we have seen some true-life wonders of the world — giant Galapagos tortoises slumbering in great basins of mud; sun rising through the mists at Machu Picchu; South Carolina’s massive Angel Oak, whose half-millennium-old canopy produces some 17,200 square feet of shade; and the HET, which we chanced upon along our back-roads drive from half a week of high-brow art immersion at the Judd and Chinati Foundations in Marfa, Texas, to the fiftieth anniversary of the alien landing in Roswell, New Mexico. Somewhere between them, the HET rises up, a great white apparition atop a rounded mountain in a dry scrub forest of the American Southwest. I don’t know who noticed it first — my friend or me — but you can see it from miles around, so startling a presence that you think — you can’t help but think — whose planet is this, anyway?

Of course, we stopped. It was there.

We parked in a remote lot and then walked up the hill in a blast of midday sun, eventually making our way to a tour that began in the cool marble foyer of the telescope itself. After some preliminaries, the guide led us to an observation platform where we could gaze down through a glass shield on a room of astronomers, intent at their computers, and up to the vast dome above. There, we were told that, in keeping with the general trend in telescopes toward diminution, the HET is a segmented dome — a little like a honeycomb — comprised of ninety-one separate mirror sections fused together so precisely you cannot fit between them even half a human hair. Working as one, these fused mirrors give the HET an effective aperture of nearly ten-meters, which made it (at the time), scientifically speaking, the third largest optical reflecting telescope in the world. I thought about that for a while, and then I thought about half a human hair. Even now, all these years later, it’s hard to resist the urge to pull one from my head just for the marvel of it.

By comparison, Roswell was a bust.

We’d missed the big costume parade and alien lookalike party by the time we arrived, and a lot of the celebrated experts on what went down in Roswell were nowhere to be seen. That’s what I would do if I were them — disappear. You’d get tired of the gawking over time.

The exhibition hall was open, though, and in the conference rooms, some late panel sessions were still going on.

First, we went to a discussion on abduction phenomenon that featured a couple of psychologists and a somewhat scrappy abductee who referred to himself as “the Alien Hunter” and claimed to be pretty much an expert on all things ET. Here’s what he told us: whatever you think about extraterrestrials, you’ll likely be wrong. Ask the average person what an alien might look like, and most won’t do much better than some worn out cliché of little green men gleaned from B-grade science fiction, but real ET’s are brown or blue, and they’re not at all small, but big — sometimes very, very big. The blue ones are tall and willowy and smart, and they are the ones who experiment on you. The brown ones are short and squat and stupid, and they are the ones who zap you away in the night — hapless errand boys for their cruel masters above.

All aliens are evil and confused by water.

Then the Alien Hunter offered, as proof, how not so long ago a suburban mom in Texas was bereaved of her two toddlers when the aliens returned them to the wrong backyard body of water. The mom was ironing through it all. One minute, her two babies were having fun and splashing in their little blow-up kiddie pool just outside the kitchen window, where she could keep her eye on them; then, half a heartbeat later, they were dead in the deep end of the next-door-neighbor’s swimming pool.

The aliens took her, too, at the exact same instant as they took her kids, but it was all over before any of them knew what was going on because aliens can bend time and consciousness to make you think things are happening that aren’t. What happens is — it’s hard to explain — they take you up and experiment on you for what seems like days, or weeks, or even years, but when they’re done, it’s like no time at all has passed. After that, they plant screen memories in you, which is why so many children are afraid of clowns. Terrible things went on in that spaceship, but when the mom looked up, the iron was still hot on the board before her, the white shirt still smelling of steamy starch, and in the neighbor’s backyard pool: No! No! No!

Except, the Alien Hunter said, there wasn’t any water in those little baby lungs. Not water — something else. Does that sound like drowning to you?

And a Texas Grand Jury agreed, because when the mom was brought up before it for killing her babies or just plain neglect, they let her off on account of the fence between her yard and the neighbor’s yard (and how could little babies have jumped a fence like that?), as well as what she told them about what happened with the aliens.

But yet that — her abduction, her own kids dead in her neighbor’s swimming pool — wasn’t even the worst thing. The worst thing was thinking what the aliens did to her babies when they had them in their spaceship. Maybe not the same as what they did to her; maybe something worse.

They’ll bring you back, the Alien Hunter said, but they won’t bring you back the same.

The only way to stop an alien, he said, is to look it in the eye (except their eyes aren’t eyes but membranes) and say: “In the name of God, I command you to go.”

You can point if you want, but it’s all in the words, which you need to keep on the tip of your tongue if you want to stay safe here on Earth.

***

Next, we went to hear an astrophysicist give a talk about a solar system on the far side of the Universe that turns out to be an exact mirror image of our own. Billed as a renowned scientist on leave from an R1 Research University to pursue this groundbreaking new work, the speaker was a tall man, red-faced and rangy, with big hands and an elaborate PowerPoint presentation of technical schemata for advanced rocket ships and mathematical algorithms for interstellar travel. As he led us through the physics of warp-speeding from one galaxy to the next, it was easy to imagine him as a popular professor — students always like it when you get worked up like that. By the end of his talk, his forehead was dripping with sweat, his shirt soaked, his hair a mess.

When I say exactly, he said, I mean exactly: there’s one of you here, one of you there — living proof we’re not alone.

Now I can’t remember: Did the audience go wild? Or did a sober hush fall over us as we took in the idea of another audience, exactly like us, taking in the same idea — us a mirror image of them — billions of miles away?

Sometimes, even now, I think about that solar system, its twin of our Earth orbiting its twin of our Sun, and what I think is, If there’s one, how many others must there be?In an infinite space, an infinite number of Milky Ways, which, again, you have to wonder: Does this include an infinite number of our twin selves, brushing our teeth and suffering late-night bouts of alien-induced insomnia?

Then I think: The other side of a curved Universe is right there beside us, so close as to turn into what must be a kind of hole, folding us in on ourselves to infinity, and ever-expanding.

I think: When you command them to go, would it hurt to at least say please?

A Junk Heap of Noise

Other proof of life in outer space we saw in Roswell included a to-scale model of a nineteenth-century phantom airship and a real-life replica of the skull of a hybrid child born from the coupling of an alien with an Aztec warrior. It’s said that when you touch it, you feel something deep inside you, like a primal recognition or the strange sensation of looking at the sun.

Hi, little alien brother, you want to say.

But they don’t let you touch it, only look.

Meantime, those 42 radio telescopes of the ATA are out there listening, the most sensitive ears on the planet perpetually tuned to the heavens.

Hello, out there. We’re here.

But no, that’s wrong: they’re receivers, not transmitters. Our airwaves are a junk heap of noise as it is; no need to go to any extra trouble sending special messages — Greetings from Earth, we come in peace — although it’s hard not to wonder what the aliens will make of Fox News or the blues. And what’s going to happen if we do pick something up, some burst of alien chatter or deeply coded message. How will we even recognize or understand it?

According to the SETI Institute, no one really knows, but the ATA hugely increases our chances of at least hearing something.

A couple of years ago, I was driving home from school when NPR reported that NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope had revealed the first known system of seven Earth-sized planets around a single star — TRAPPIST-1 — only 39 light years from Earth. Of those seven, three are firmly fixed right smack dab in the middle of what NASA calls the “habitable zone,” the area around the parent star where a rocky planet is most likely to be not too hot, and not too cold, for liquid water. And TRAPPIST-1 is only one of a thousand or so stars we’ve had the capacity to survey so far; the ATA gives us potential access billions more.

I don’t use the word billions lightly, either.

But, as senior SETI astronomer Seth Shotak has observed, preliminary analysis of NASA’s Kepler Mission to search for Earth-sized and smaller planets — places where we might find life — suggests that the number of habitable planets in our own Milky Way is “in the tens of billions, minimum. And we haven’t,” Shotak adds, “even talked about the moons.”

With some 9,000,000,000 narrow-band radio channels on which aliens might be trying to make contact, surely someone’s out there speaking, and to us: from their mouths to our ears.

One difference between the SETI Institute and Roswell is transparency. SETI, for example, has signed a public pledge (you can read it on the internet) to let us know just as soon as they hear anything at all, whereas a lot of people say the government’s been hiding information about Roswell since the aliens first landed there in 1947.

Even so, I wonder if everyone is going to be so glad to know when it happens, so open-minded and welcoming as all that. Forget the screaming mobs or ecstatic cults we all know from the movies, and just imagine it in real life: You’re sitting with your laptop, playing brain games or answering a backlog of email, when a breaking news alert pops up on your screen: aliens make contact. Any way you look at it, it’s going to be big — potentially as big, the SETI Institute says, as Copernicus’s discovery that Earth is not the center of the Universe.

We’re not alone? we’ll say. Not alone? We’ll say it in all kinds of ways. We’ll say it with awe, terror, jubilation, vindication, and flat-out denial. We’ll hide in our cellars and dance in the streets. All this will happen one day.

As for me, despite the hybrid child’s skull, my own deep urge to touch it, and those seven exoplanets with their potential oceans, I’m still on the fence. The SETI Institute says that once we make contact, at least we’ll know for sure. But what exactly will we know? And how should knowing be any consolation to us?

Surely the astronomers who turned out to be wrong — all those, for example, who predated Copernicus — meant well. Maybe they weren’t playing with a full deck, but when they looked at the heavens, surely they felt something — something deep — just like you and I do. You look up, and there they are — all those stars. And then something inside you goes as still as the spaces between the beats of your heart, and you’re just standing there, looking, and that’s when the mystery begins.

The Largest Black Hole in Our Galaxy

As for the astronomer husband of my sister’s best friend, I don’t know what he thinks about extraterrestrial life, but I do know that the large millimeter-wave dishes at Hat Creek during his tenure had, by 1987, expanded from the original two to become the Berkeley-Illinois-Maryland Array (BIMA), jointly operated by UC Berkeley, the University of Illinois, and the University of Maryland. Then, in 2004, the nine 6.1-meter BIMA dishes were bundled up and moved to Cedar Flat in the Westgard Pass of California’s White Mountains, joining seven telescopes from Caltech’s Owens Valley Radio Observatory (ORVO).

Together, for a while, this jointly operated Combined Array for Research in Millimeter-wave Astronomy (CARMA) — which expanded again in 2008 when the University of Chicago brought the total number of telescopes to 23 — functioned as the most powerful millimeter interferometer in the world. And then, in 2015, it was decommissioned, the telescopes relocated to ORVO for storage. I don’t know what goes on at Cedar Flat now. Meantime, in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile, the internationally operated Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), which broke ground in 2003 and today includes 66 radio telescopes, has succeeded CARMA as the largest such array in the world.

I remember when my astronomer friend — for over the years, I’ve come to think of him as a friend, although we’ve only seen each other a handful of times over the last quarter century, and on each, I was just tagging along with my sister — was packing up his telescopes in preparation for the transition from Berkeley to the SETI Institute. I remember, if more vaguely, the first time gave me a tour of the observatory and what must have been its control center, which I remember, if even more vaguely, as a massive instrument panel below a curved bank of windows. There were lights and levers and knobs and screens, just like in a science fiction movie, and when my friend flipped a switch or dialed a knob inside the control room, outside, the telescopes shifted. Data gathered at Hat Creek has made substantial contributions to our understanding of such galactic phenomena as stellar birth and early planet formation, supermassive black holes, galaxies and galaxy mergers, and sudden events like gamma-ray bursts and supernova explosions. When my friend turned the telescopes for me, what new signal did they pick up?

It was thrilling, really — the mysteries of the Universe unfolding all around us, us,inside the Universe. Puny is not small enough a word, but yet it comes to me. The other words that come: as one. We stood there, as one with the Universe, the broad panel of lights blinking before us, both testament to and mockery of our humanity.

All that was a long time ago.

***

A few years ago, my sister and I were driving down California Highway 395 just south of Bishop, when she cried out, Look, there — I think I see them!

So I stopped the car and we got out to look, and maybe they were out there, the original HCRO telescopes, and maybe not. But we saw something — giant convex disks hunkered down on the floor of the valley at the foot of low, dry mountains, home to a stunted forest of Great Basin bristlecone pines, among the oldest trees on earth. This gave us such a feeling of, I don’t know, warm-heartedness — there, just across the valley, our friend’s old telescopes, still being telescopes after all this time! And maybe we gave a little cheer or hug to celebrate all the odd connections of our lives. But it wasn’t until now, writing this, that I’ve understood that even if what we saw was ORVO — we were in the Owens Valley, after all — and that even if it really did include the same telescopes we both fondly remembered, by the time we saw them there, they were probably already mothballed, no longer serving any earthly purpose at all.

How do you even move a telescope, I wonder? Do you hoist it on a flatbed truck and bolt it down with nuts and chains, as if it might loft itself into the sky like a flying saucer all its own? Does it wag a yellow “Wide Load” warning behind it? I like to imagine all nine of them parading down the long, desolate highway that skims the east side of California’s Sierra Nevadas — a haunting procession of ghostly beauty from another century, alien captives. It’s more likely, though, that they were disassembled, boxed up in anonymous crates, and red-stamped as Fragile. No one, seeing such crates, would have known what was inside them.

Either way, the telescopes were sent off, and I sometimes try to imagine how my friend experienced their absence. Was he sad to see them go? Did he miss them, feel empty? People develop feelings, after all, for their cars and ragged shoes and sweaters, and he worked on them for years, so why not? I almost love those old telescopes myself, and I only saw them a couple of times. But every time I did, I wanted to crawl inside them, curl up in their centers, and lie bathed in whatever it was they were listening to — alien chatter, perhaps, or the spectral music of the spheres.

Beyond that, my friend’s own research specialization is black holes, or not so much black holes, per se, but a supermassive black hole believed to be the largest one in our galaxy. I think it’s in our galaxy, but it could be in another one. Once you get into the galaxies, it’s easy to lose track. On Earth, this man is a rock hound, a collector of local lava and phosphorescent exotics from remote locations on the planet. But up there in space, it’s the absence of any known matter — the absolute lack of rockiness — that captivates him. It’s said that this absence is itself the paradoxical effect of ultimate rockiness — matter so dense it deconstructs itself, becoming anti-matter.

I don’t pretend to understand this.

The Universe Will Not Be Mastered.

When I was a girl, I knew a boy who wanted more than anything to become a WLE. By WLE, I mean exactly what he meant: World’s Leading Expert. He didn’t really care what it was he knew more about than anyone else on earth; it was just the idea of becoming a WLE that had seized his imagination, taking root inside him like a hunger or a thirst. You look at boys these days, glued to their screens and with their small devices in their ears, and it’s impossible to imagine a time when a boy could think like that. These days boys aim higher, think Master of the Universe, but that only happens in video games. And of course, the internet makes WLE’s of us all.

But it wasn’t always like this.

Imagine, instead, a time before now, in another century, before the internet, before even cable TV. Imagine a boy in a town with a bike, a pile of library books. This boy, my friend, was curious, ambitious, and cagey. Cagily, he reasoned that the fastest route to WLE domination in any knowledge category was to pick a subject about which not much was known to begin with. So he picked bats.

Today, he’d be referred, diagnosed, most likely, medicated. Back then, he was just eccentric; we admired him for it. We were rooting for him.

This boy had big ears, a broad face splattered with freckles like stars, and a tendency to flush. He also was the only boy I knew who did not have a father, and it sometimes seemed to me that he might as well as not have had a mother too, since the one that he did have was what we used to call a “shut-in,” a woman who never left her room. Without normal parents, he had no one to drive him around, so he rode a bike instead, making him, as well, the first person I knew to use a bike for actual transportation. You could often see him, pedaling all over town on his quest for bats in their native roosts — church steeples, barn rafters, cave overhangs — where he’d climb up or crawl in, scoop them into a bag, and then pedal them home to hold captive in a little bathouse he’d built in his backyard out of cinderblocks and what looked like glue.

His plan was to keep them in there long enough to disrupt their natural homing instinct and make them home, instead, to him. The bathouse had a one-cinderblock opening covered with a piece of plywood through which he slipped the daily feedings in — old fruit, banana peels, bugs. He did this for nine months — the length, he may have reasoned, of a human gestation — notching each day on the outside of the bathouse with a knife until the nine months were over.

I imagine him now red as a beet when the time came at last to test his theory. For months, he’d only peeked at his bats, peering in at them inside their cage, the beam of his flashlight reflecting off their beady eyes and velvet fur. Now he would set them free.

I wish I could have been there — I wish someone could have been there. It must have been exciting to watch them crawl out and fly away into the dusk. And then he waited. He may have waited out there all night, convinced that his bats would soon be coming home to him.

And so I imagine him too, the next day at dawn, a sleeping bag or afghan wrapped around his thin shoulders, growing paler and paler as his vigil stretched out from the glow of early morning to the bright glare of day. It’s sadder for me now than it was when we were kids, because in retrospect, it’s clear he must have fallen a little bit in love with these gentle, furtive animals he’d never see again.

Things disappear: bats from a childhood dream, matter into black holes, blooms from a tree, the years of one’s raveling life. I’m moved, of course, by the loss of what may be as close to the only real family he would ever establish, but am, at least in equal part, intrigued by what motivated him to begin with, his sudden, arbitrary ambition, and its corollary drive to mastery. I know this drive lies somewhere at the heart of human progress, but I still don’t understand it.

Perhaps it’s peevish to say so, but endings, at some level, bore me. They lie there ahead, pre-determined and already known. In general, I prefer the ambiguities that lie along the way, the big and the little surprises you didn’t expect, the mysterious spaces between.

***

Any astronomer whose job it is to manage an observatory will find himself in an unenviable position. The instruments with which he spends his days and nights to keep things running smoothly will become, over time, his most intimate relations, yet he’ll never have them to himself or squirrel away enough time with them to complete his own research, because his first obligation is to hand them over — and over and over — to the visiting astronomers whose work will always — always — take precedence over his own. During periods of heavy use, it will be like watching the woman you love in the arms of other men — demanding men, imperious men, lesser men than you. Although some of them will be women.

This was not my astronomer friend’s first remote telescope — he spent years in the Outback of Australia — but it would be his last. Throughout his time there, he would be, like my childhood friend, secretly, or not so secretly, in love with his supermassive black hole, about which he’d become, hands-down, the World’s Leading Expert. He once told me that he’d accumulated an immense pile of unresolved data, that he’d glimpsed things in it no one else on the planet would ever see or understand, that nothing gave his life more meaning than this, these rare scattered moments of insight and bliss. Retired now, he’s still sitting on this pile of data, but will never be able to fill in the gaps, never synthesize his life’s work because, first they’ll take away his telescopes, and then, his life’s work will be over.

As for me, I’m more inclined toward Heidegger’s tree in bloom.

“We are today,” the philosopher wrote, “rather inclined to favor a supposedly superior physical and physiological knowledge, and to drop the blooming tree … The thing that matters first and foremost … is not to drop the tree in bloom, but for once to let it stand where it stands.”

I know about my astronomer friend’s black hole. I think about it often. There’s so much we won’t ever know about it. You can’t stand next to a black hole, of course, but maybe it’s okay to let it stand.

***

After Roswell, my friend and I drove down to Carlsbad to watch the bats soar out of their Caverns at the National Park. Like those of my childhood friend, they swarm out at dusk all at once, a vast and spiraling cloud of bats pulsing like a single organism — but they don’t come back like that. They trickle back, instead, in ones and twos, sated by their night-long meal of some 1200 insects per hour, slipping into the Caverns like stealthy intruders, even though it is their home. They have performed this dusk exodus right on schedule — so predictably that you can tell time by it — for as far back as human records go, but as yet no one fully understands it.

My sister likes to name things. When we hike or backpack, she’ll bring pages torn out of books to help her identify the things we see — birds, flowers, rocks. Sometimes, she’ll hunker down to study her pages, unsure whether whatever she’s observed is this or that. She can often spend more time examining her pictures than the thing that stands before her that the pictures might — or might not — depict. We have often argued about this.

Between knowing nothing and knowing everything, surely there’s a middle ground that lets things stand. For if there is any one thing I can say for certain, it is this: the Universe will not be mastered.

Not the Universe, not the bat, not the tree.

At Home on Planet Earth

On the day I climbed Mount Lassen, I found myself a woman on the far other side of my life from when I used to climb it as a girl. Now a mother of men, the cells of my own body have been replaced so many times that I cannot even be said to be the same person as the girl who once knew a boy who loved bats and with whom I might have been a little bit in love myself. And yet, I thought of him now as I rested on the peak of the mountain I’d just climbed, luxuriating in what I imagine to have been a calm and meditative state.

Between where I sat that day and the ATA below lay Lassen’s geothermal hot spots, where, years before, I had received my life’s first lessons in geology. We used to go there for family picnics or to take the hike through Bumpass Hell. It’s not really much of a hike, more an easy stroll among the fumaroles and simmering lakes, the thinly crusted mud pots and preposterous creek beds of unnatural hues — pea yellow, ice blue, the flat red brown of my own scabbed knees — left behind after sulfuric acid breaks down the hard, gray-green andesite lavas into colorful clays and iron oxides. An imaginative child, prone to dreaminess and wandering, I was closely watched and sometimes grabbed abruptly from behind to prevent my drifting into a steaming vent or pond where I might be boiled alive or overcome by molten mud. For days afterward, I’d taste the stink of rotten egg on the back of my tongue, smelled it on the skin of my forearm, dreamed it. In my dreams, the world seemed terribly old, and I’d wake feeling oddly embarrassed by its inner workings, its ineffable fragility.

These days, when I travel, I’m sometimes struck by the similarities in the terrain of the places I visit and those I’m most familiar with, at home in California. The hills may be lower, perhaps, the vegetation, lusher. But wherever you go, you are at home on planet Earth.

Lassen’s summit trail is a short but vigorous hike — two-and-a-half-miles of implacable switchbacks that slice their way to the peak in a rise of two thousand feet that any fit and able-bodied person can make in good time, which is what I had done. At just over 10,000 feet, the air up there is still rich with oxygen and, except for the wind, not even cold on a summer afternoon, especially in the shelter of the black hard lava boulders, warmed, as they are, by the sun. On the whole, it’s the kind of place where time stops and where you think, if you think anything, you might never want to come down.

Meanwhile, far below, the ATA spread its cluster of wings in a field of such enormous optimism that it almost seemed the aliens had already landed. Like them, on this day, I was listening, hoping maybe, at this altitude, I’d hear something too. Maybe the aliens would speak — and to me.

Mostly what I heard, though, was wind, dry and cold and whistling. It carried — I don’t know — the sound of hikers ascending, their puny human voices amplified unnaturally in that thin air, the skittering of dislodged rocks.

We think of bats as silent creatures, but in fact the noises they make are just two or three times higher than we can perceive. What else is going on out there, beyond our human register? How long must we listen, how still must we be, to pick up the signals that might, even now, be enveloping us? For although I have long suspected that we’re largely on our own on planet Earth, it doesn’t hurt to allow I might be wrong.

I hope, when the aliens come, they will feel at home here too.

And yet, like us, they will only be visiting. Our time on Earth is limited. Looking back, it’s clear we should have been more gracious guests, but we are no match for nature, which will one day slough us off. If there is any solace we should take from our extraterrestrial guests when they finally make contact, I suppose it might be to somehow make peace with the pure, unfathomable soul of the Universe itself, its utter indifference to us.

If you ever shone a light into space as a child and marveled to imagine that, if nothing stopped it, it would go on and on forever into all infinity, you will know what I mean.

So the next time there’s a clear night sky, go out and look up into it. You can use a flashlight if you want, but you don’t have to. Just stand and look and listen, and let things stand. Do this for a long time.

And breathe.

************************************************************************************

Katharine Haake’s most recent work is a chapbook of fabulist parables, Assumptions We Might Make About the Postworld, a 2018 release from Ricochet Press. Her other books include The Time of Quarantine;That Water, Those Rocks;The Origin of Stars;The Height and Depth of Everything;and No Reason on Earth. Kate’s other writing has appeared in such magazines as One Story, The Iowa Review, Crazyhorse, New Letters, and Witness. She is also the author of What Our Speech Disrupts: Feminism and Creative Writing Studies, and, with Hans Ostrom and the late Wendy Bishop, Metro: Journeys in Writing Creatively.