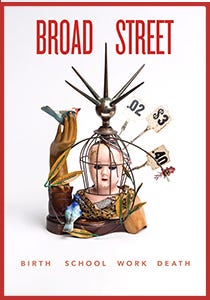

Portrait of the author as a young auteur.

“We had arrived with vision. Golden children with artistic streaks. Golden children with talent and means, certainly, and cocky attitudes. Auteurs.”

1.

At what tragic point did we begin to think that film school might not be all it was cracked up to be? We had arrived with VHS copies of our favorite films and movie posters of our favorite films and video cameras that our mommies and daddies had bought us for graduation presents. We had arrived with half-finished scripts or fully finished scripts that just needed a polish. We had arrived with journals that were filled with ideas that could be turned into scripts. We had arrived with vision. Golden children with artistic streaks. Golden children with talent and means, certainly, and cocky attitudes. Golden children with time on our sides — time, everybody wants time. We arrived with the idea that we were going to be the next Spielberg or Fellini or Scorsese or Allen or Lee. Auteurs.

So we thought.

The film school of New York University, Tisch School of the Arts, was located at 721 Broadway. It still is. I attended classes there from the summer of 1989 to the spring of 1992. As a transfer student from a Catholic university in the Midwest, I did not have to take any core classes — say, the Evolution of Western Ideas and Institutions to the Seventeenth Century; or Knowledge and Reality: Metaphysics; or Chief British Writers II; or Introduction to Poetry. These requirements were already completed. There was one exception that might clue you into my academic Achilles heel: a three-credit math-science core course. The course load I took at NYU then was mostly a series of integrated film classes. I wrote scripts in Writing the Short Screenplay or Dramatic Writing, and I shot them in Sight and Sound or Narrative I or II, which I assembled in Editing I or II.

The work for Editing I or II occurred — or was supposed to occur — in the edit suites on the ninth floor. The competition to book those edit suites could be fierce, especially toward the end of the semester. Once we got into one, our time was limited. The edit-room staff routinely knocked on doors, kicked people out, and let others in, while all those unminted auteurs with means circled the floor like vultures awaiting their carrion due. Many of us felt we needed more time — and a more relaxed environment — in which to tinker with our projects, perfect them, so we would rent out independently owned edit suites overnight in Midtown. These suites were almost always on the top floors of old buildings with creaky elevators or no working elevators at all. Buildings where the medicine-green paint was chipped and the radiators hissed and sprayed and at two in the morning on the twelfth or fourteenth floor you could open a window and smoke … or jump.

What was most memorable about those nights on the high floors was the light of the Steenbeck that allowed the picture to glow. Those moving frames. The Steenbeck was a flatbed system that allowed us to sync and edit a motion picture with two or more tracks, depending on the machine. There were buttons and knobs on the Steenbeck that controlled the speed at which the film ran through, so we could watch it fast or slow, or we could pause the strip to consider and then mark our frames for the edit.

The edit put the picture in order, brought our visions to life. There was a feeling on those high floors, in rooms that we had until the sun began to creep over the East River, that we had stepped outside of normal time.

2.

The first time I sat in one of those edit suites in Midtown was when I was cutting together “Epic,” a six-minute black-and-white film with two tracks, for Sight and Sound. It was about a man searching throughout the desert for a treasure. To create the illusion of a desert, I framed the beach at Coney Island in such a way that the water and background — the Ferris wheel, the roller coaster, the parachute ride — were not seen. The man who walked through the “desert” that day was a fellow student with long blond hair, a denim vest, and a sweet biker’s ass. He must’ve known that I had a crush on him, even though he never said anything about it. Nor did he say anything when I asked him, over and over again, to trudge through the sand on that windy day so I could record him in close-ups, medium shots and long shots, high and low angles, and those experimental canted frames. I even spun the camera around 360 degrees so there were points when he wasn’t even in the frame. There and not there, see? I was being what some might call “creative” … or annoying … or just understandably excited at the new tools at my disposal — an Arriflex camera, a tripod with moving head, a light meter. Eventually I asked this man to start digging in the sand so he could come upon a box. Inside the box is a key. The film ends there.

I’m sure this film had some esoteric point, a comment or consideration on the meaning of life, perhaps. That was the impossible theme upon which many of my early efforts hinged. Whatever the point, it was broad and could only be “gotten” if one could decipher the symbols that I planted in the picture. The box, the desert, the key all stood for something, you see. Fresh from an Introduction to Poetry class in the Midwest, I naively thought that symbols mattered as much as, or more than, story.

I had not been careful that day at the beach with that blond man (maybe I was too focused on the biker butt), and sand had gotten lodged into Arriflex camera. The woman in the film cage, who had Cheeto-colored hair and yellow teeth and an axe to grind, told me that I would either have to pay for the camera to be professionally cleaned, or I could do it myself. So one day I donned white gloves and dipped long cotton swabs into alcohol and very carefully began to extract the residue of that early effort, a pointillist in reverse, removing all the precious dots from his mechanical canvas.

This was not the only film I shot at Coney Island. The next semester, for Narrative I, when we were no longer shooting in black and white but in color, I rented a van and drove a cast and crew to a cement ruin under the old parachute ride. My producer, another student, knew an actor who had a recurring role in a sitcom — The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, if I remember — and a model who wanted to break into film. They agreed to partake in “Edge of the World” as my leads. The dialogue begins:

BRIAN: Where are we?

THANATOS: Thanatopsis.

BRIAN: Wh — …what do you mean?

THANATOS: Can’t you feel it?

You may not be able to see where I was going with this film, but I do. Brian has just died and has found himself in a strange land called Thanatopsis, which is represented by the old parachute ride and surrounding areas at Coney Island. Thanatos, a nymph or guide or demon from the other world, materializes in front of Brian and spends the entire script (five pages, roughly five minutes) explaining to Brian why he has landed in this purgatorial spot. Then the death vamp disappears. Brian is left alone.

Not surprisingly, this film never received its place in cinematic history, never was nominated for Best Short Film — Live Action by the Oscar committee, never crowned with a Golden Bear at Berlin or a silver stag or fluorescent unicorn at an intimate festival in some out-of-the-way region where old ladies roll out sheets of brownies for the premieres, because I never cut this film together. The reels still reside in a temperature-controlled vault at DuArt Film and Video on East Fifty-Fourth Street in New York City.

You may infer that I was a young man who seemed to lack a basic understanding of how to tell a story. One who might have understood that a story needed a setting, characters, an interesting premise, and conflict (two people who want different things), but failed to grasp how things actually happenedin a screenplay. Or in life, for that matter. The comments provided by the professor — “he gets there too easily; not enough obstacles” — provided one clue as to what was wrong with the script.

I’m telling you about a time when I was not so interested in listening to what men or other figures of authority might wish to tell me about the filmic form; not so interested in the apprentice-mentor or teacher-pupil construct, even. I thought I had all the answers. This was not an uncommon attitude or affect of an individual attending an expensive university program on the East Coast in the late twentieth century.

Some of the better professors did try to change my course. Others saw the vacuity they were confronted with — those blank eyes with enlarged pupils that wanted only to reflect the Oscar statue — and simply turned away. They turned away, and I and my classmates dove into productions with so-so scripts, scripts that lacked basic dramatic elements, scripts that contained no clear obstacles, scripts that were, well, experimental — “continued motion through discontinued space,” radical jump cuts, absent plot lines, light flashes, film scratches, superimpositions, slow and fast motion, no motion, stills, black space.

3.

I crewed on a couple of Holocaust documentaries that were shooting around town at this time. The survivors were aging and there was an extra push to get them on film so their stories would not be lost or forgotten. We filmed these men and women in their homes so that they would be as comfortable as possible as they related their experiences.

Their homes had what might be called a “suburban feel” to them. All the appliances were new. The air was central. Framed pictures of grandkids were polished and placed in prominent spots on end tables and bookshelves and walls. A plate of cookies or rugelach was usually set out for the cast and crew on a Formica countertop patterned with gold confetti. There was a feeling that nothing bad would ever happen in those well-kept homes.

It was only after the camera began to roll and as the survivors began to speak — the Nagra measured the audio levels, crystal sync — that I could feel the measured air perceptibly shift. What had been light and ventilated, suburban clean, grew heavy and black. Closed off. Suffocating. We rolled until the film ran out, and then it was just a quick magazine change, a quicker sound check, a clap, and we were rolling again. We were rolling again and we were listening again and we were entering that dark place in our history again. Holding on. Witnesses to the witnesses.

I went to a high school that never seemed to get around to teaching us about World War II.This material was always placed in the last chapters of the social studies textbooks, and we always ran out of time at the end of the school year to cover it. Social studies textbooks, not history ones. Already, we were more interested in the broad themes of society than the specific tragedies of humans in time. Many of the social studies teachers at that time were Civil War recreationists too, so the focus of our historical learning always felt skewed. They preferred muskets and munitions to the madman with the manifesto. Maybe they didn’t think we could handle discussing the extermination of six million Jews — along with gypsies, homosexuals, intellectuals, and all others who might be considered different — and maybe they were right, and maybe they should have just done it anyway.

4.

There was a time, pre-9/11, when it was fairly easy to enter the building at 721 Broadway. The flash of an NYU ID was more suggestion than requirement. So there were always new faces lurking in the halls of Tisch, offering to provide services — take photographs, act, hold the boom pole, bake — to build their résumés and to connect with the energy of the film community. Intelligent creatures, I see now, who knew how to acquire an education without ever actually having to pay for one. Hustlers.

I did not at this point understand the world of the hustle. I was not versed in the ways in which one stranger approaches another in the lobby or hallway of a creative building and then presents the person with a résumé or a headshot or a phone number scribbled on the corner of a legal pad. There is a way to shake hands, make eye contact, smile. Wink. The flirtations that function as calling cards. Back then, I still thought that relationships, like art and love and growth, required time. I was wrong about all that. In New York, things could happen in a flash, boom, you’re in there.

Even at Coney Island during the shoot for “The Edge of the World,” some street punk offered to hold the boom for a free lunch. My assistant director dated him for a while, or just slept with him for a night or two, and my sound man used him to crew on his project (a horror flick that took place at a Krispy Kreme doughnut factory), and soon he was a regular feature in the living rooms and local parks and sound stages where my classmates shot their pictures. I even ran into him one night on the ninth floor edit suites. He was “really groovin’ on the cut.”

5.

I learned about editing from an editrix named Lilly Koffman. She was putting together an American Masters documentary on a famous Russian dancer. I was “hired” as an apprentice editor (read: intern) on this project.

I think Lilly felt bad that they didn’t have enough money to pay me, so she invited me over for dinner one night in the middle of the edit. Lilly lived at the top of a six-floor walkup on Mulberry Street. New York stairs: black-and-white tile with a simple geometric pattern, worn in the centers, dirty around the edges. On each landing, you could pause and look out a barred window with no screens and stare onto the street while you caught your breath.

Lilly gave me a European kiss as I entered, one peck on each cheek. She took my coat and hung it over the edge of the bathtub that sat in her kitchen. She then pivoted her body toward the counter so she could place two large ceramic bowls in the center of an old wooden table. In one bowl, spiral pasta with dried tomatoes. In the other, a dark green lettuce with long leaves.

“Looks like weeds,” I said.

“Arugula,” she said.

She pressed Play on her CD player. As the first chords of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater filled the apartment, she ducked her head out onto her fire escape to pick some oregano and basil. She ripped the herbs and sprinkled them on top of the pasta dish. She poured wine into juice glasses and said, “The nectar of the gods.” As a particularly beautiful passage surged through the speakers (bold, revelatory), we lifted our glasses, toasted to first and last suppers. One could almost see Mary the morning after looking at and then turning away from the crucifixion of her only son. The resolution of sin.

Lilly and I were soon engaged in a conversation — or should I say, the shadow act, confession? Lilly talked about the abortion she had in her twenties, the one in her thirties, the affair she was currently having with the psychoanalyst who had a wife and three kids, the stunted sister who resided in a home upstate, one of the genetically mutated who live in a divine perpetual state. She asked me what I thought about Bill’s dog? William “Bill” Hurt (Accidental Tourist, Kiss of the Spider Woman, The Big Chill) had been hired to record the voice-over for the documentary we were working on. I was put in charge of walking his dog, which wouldn’t be mistaken for a mutt, in the southern portion of Central Park.

“I don’t like picking up shit,” I said.

“Are you seeing anyone?” Lilly asked.

“Falling in love with people who don’t love me back,” I said.

“That’s happening for a reason,” she said.

Do things always happen for a reason?

“What’s your relationship with you father? Your mother?” she asked.

Lilly, I see now, was searching for Freudian logic in a post-Freudian world. The way we commit ourselves over and over again to our pasts. We talked about the danger of love. About poetry, Pergolesi, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” Blanche DuBois, Babs. We talked about the Holocaust, Sylvia Plath, “Daddy,” daddies. What we were all searching for, and why, and how in the hell were we going to score enough money to tell the stories that we were burning to bring to life on the screen?

In the middle of eating dinner, Lilly walked the few steps to the toilet. She left the door cracked open.

“Americans have hang-ups about shit,” she said from the toilet. “Europeans, about sex.”

“Can we talk about the female orgasm?” I asked.

On her way back to the table, Lilly pulled a clear bottle of vodka out of her freezer. She was trying to cut down on her drinking at this time. Just not on that night.

We were all trying to cut down on our drinking. We always would be. What we wouldn’t always be doing was climbing up six flights of stairs on Mulberry Street. The stairs would remain — of course, the stairs always remain: fires or blackouts — but in the not-so-distant future, the company that managed the complex would install a shiny silver elevator to carry the tenants and their animals up and down those long flights. The days of snaking upstairs in this and other old tenement buildings were numbered, and I’m not so sure that’s such a good thing.

6.

Marla Hanson was the twenty-four-year-old model who was pulled into an empty parking garage on June 5, 1986, by two men near the Lincoln Tunnel. The two men were hired by her then-landlord, Steve Roth, and instructed to cut and slash her face with razor blades. Hanson thought the men were going to rape her that night, so she was trying to stay standing up. That was her goal. “They can’t rape me if they can’t push me on the ground,” she reasoned. She didn’t even realize her face had been scored until she saw the blood on her fingers. She would lose twenty percent of her blood on that night and require over one hundred stitches. “Model Slashed: An Ex-Landlord Is Among 3 Held” read the headlines in the New York Times the next day.

I knew Marla because we sat next to each other in a class that surveyed the national parks of America. This was a blow-off class that fulfilled the math-science core that I needed to graduate. I remember little of this course, save for the saturated cover of the assigned textbook: a picture of the arch in Bryce Canyon National Park. Hanson wrote her phone number on the inside cover of that book. A 212 prefix. They were all 212 at that time. And there were no cellular phones, just landlines, which were connected to answering machines with little red buttons that flashed in our rooms at night. Signals of life and love and good news and bad, beacons that allowed us to navigate through the dark until we found the light switch that activated all those incandescent bulbs.

Jay McInerney, who wrote Bright Lights, Big City, was her boyfriend in those years. I never spoke to her about McInerney. An aspiring writer, I didn’t want to seem like I was befriending her to meet him. I wasn’t a hustler, remember, didn’t understand how to use the people you meet (and those you don’t) to your advantage. The act was somehow incompatible in a youth who functioned more by imagination than manipulation. I’d grown up in the heartland, you see. Marla had, too. And that, one might say, makes all the difference.

7.

I had the unfortunate habit of falling in love with the men who shot my films, the cinematographers and the directors of photography (DPs). It was the late-night meetings at Caffe Reggio to work on storyboards, the heady discussions of film stocks, filters, the possibility of day-for-night. The travel to Coney Island and other areas on the edges of the city in search of the perfect locations. The rainy-day jaunts to the Angelika Film Center — one ticket and you could sneak into and out of all the theaters all day, watch every independent production, every treasure and experiment in form — to study filmic techniques that could be lifted for your own productions. Jim Jarmusch has no problem holding his shots for a really really really long time!

A day or two before production:

“We have to talk,” I would say.

“Sure,” the cinematographer or DP would say.

I’d invite the cinematographer or DP over to my studio apartment. In my studio apartment, there was a futon, special cigarettes, wine, a scented candle. If the cinematographer or DP responded positively to my confession, there was a chance that we would fall into that futon and make a crazy kind of love. Not emerge from under the sheets until we had to leave for classes the next day. Then get bagels and coffee together at the deli, walk into our classes with the flushed faces of those who had just gone the extra libidinal mile.

“I don’t have those kinds of feelings for you,” the cinematographer or DP would say.

“I understand,” I would say.

I did not understand. It would take me many years to close this projective loop.

The cinematographer or DP would hug me or not hug me and then make a beeline for the door. I’d latch the double bolt, dramatically turn off all the lights, and sit on the futon in the dark. Imagine a world where I could casually disappear, slip through the continuum, enter a dimension where I got everything I ever wanted, and more. So much more. I am reminded that when we cannot procure love — what we think of as love, anyway — when we are tossing back bottles of wine in darkened rooms lingering on the male form that has just left, when what we really want is gone, seemingly forever, the mind adjusts its sights. It starts looking at things a bit more coolly. Clinically. Demanding what one should never dare ask for. It is here, in this spare place, where we can be convinced to hand over the deeds to our very souls.

8.

I would find out during the years I knew Marla that she was operating on a form of autopilot. Back then she hadn’t really explored the trauma that she endured in that parking garage near the Lincoln Tunnel and then on trial. At one point, she rid herself of all her possessions and checked into the Chelsea Hotel.

An excerpt from a CNN transcript:

LARRY KING: …one of our producers asked me to ask you about the Chelsea Hotel, which means zero to me.

MARLA HANSON: Right.

KING: What is special about that place?

HANSON: Well, that’s where Sid killed Nancy. Sid Vicious killed Nancy. And I actually had the room right down the hall from where that happened. And that was definitely in my mind when I picked that place. It’s very dark. It’s all brown.

KING: You were really wacko.

HANSON: Well, I mean …

KING: Well, I mean, let’s pick a place where a guy killed someone, right?

HANSON: Well, it was the perfect place. It was dark and moody and artsy. And I thought, well, what a place to contemplate life or death.

The dark room. The moving frames. There is a feeling in certain rooms that you have stepped outside of normal time. Rooms that allow you — push you — to consider those existential decisions upon which the rest of your life will or will not stand.

9.

At the end of that American Masters edit, Lilly asked if I’d be willing to log some videotapes for a personal project that she was working on. I watched the first tape. There were shots from a window on a moving train — cows grazing in the countryside, telephone poles, rolling hills, even a video selfie of Lilly in her sleeper car, looking at herself in a mirror. There was a shot of the sign at the entrance of Auschwitz. She was no longer on the train, but outside, walking. (Was this the same tape, or another? Does it even matter?)

She’s inside a building now. There are shots of shoes in a glass case. These are children’s shoes, or they are children’s shoes that are mixed in with adult shoes. I don’t remember. They are all very dingy, but I can still make out some of the original colors. The reds, the yellows, the blues. There are those that tie and those that buckle and those that slip on. The shoes are static inside of this glass box, just sitting there, dead, but I see the glass breaking and the shoes pouring out onto the floor. I see myself running away.

There was actually a moment in the middle of the videotaping when Lilly had to stop her tour. She had forgotten to turn the camera off, or she’d left it on for effect, so we see the vérité jiggle and flash of floors and walls and windows. We hear her sobs, her heels on the hard floors, the lens cap hitting the camera. We know she is upset, unrooted, literally moved. It was only later that I would learn that there were people in her family line who were forced to enter those camps, never to return.

Lilly came over to my apartment and asked for the logs. I was not done.

“Pull up what you have,” she said.

I opened my computer and she saw that I had filled in only a few rows on the Excel logging sheet.

“You haven’t done a fucking thing!” she said.

She pulled her hair up in a ponytail, which made her face look pinched and tight, old even. She grabbed the videotapes and started stuffing them into her purse. The clink of plastic cases sounded like nails being dropped into a paper bag at a hardware store. She then asked for a printout of the log sheet, even though I hadn’t made any progress. This required me to pull a dot-matrix printer from the top shelf of my closet and search cluttered desk drawers for a printer cable. The paper jammed twice and I realigned it twice. The sheets were finally torn off and she was out of there.

Like a dog that was losing its master, I followed her out my door and headed downtown with her on the M2. She didn’t say a word to me on that bus. She sat there with her tight face and pursed lips and looked out the window. It was hot that day. And humid. The rains came around Thirty-Fourth Street. Her spiral hair puffed out, frizzed. I cleared my throat, turned to her to try to say something — to repent, to beg, to scream — but thought better of it.

There was nothing more to say. We’d reached that utter point where words and sounds no longer served their purpose. I distracted myself from the moment by looking at all the advertisements above the windows on the bus. Ads for Dr. Zizmore’s miracle skin cure (No more ass warts!) and ESL classes and jobs that paid twenty dollars an hour, no experience necessary. I wondered how many people on this bus used these services. Wondered how many were looking for help or answers or cures. I wondered if I would ever become the type of person who calls one of those numbers.

Lilly reached up to pull the cord to signal for a stop. A few strands of her hair brushed against my cheek. It was rough and coarse. There was an ad for a new shampoo and conditioner that smelled like grapefruit. They were selling it at the drugstore right down the street. I had just read about it. It’s supposed to make the hair real soft.

10.

Film school was almost over now. I was getting ready to leave for the pastures of New Hampshire — there was a job on an educational television show up there — so I walked through Washington Square Park one last time. It was a bright morning and there was some general activity on lower Fifth Avenue and around the park.

It was not unlike the first day of film school. On that day the squirrels had been bargaining for nuts and the students were bargaining for hits from the dealers and the old men in shorts and black socks and sandals were playing chess, the sane ones and the crazy one alike. Someone pulled a knife but no one paid any attention. Gay men were cruising the bathrooms and there was a tourist bus circling the park, a man with a microphone reciting historical facts. There was even a famous person or almost-famous person, Kevin Bacon or Robin Byrd, spotted walking through the square.

I ordered my coffee that day with shaved ice and milk because the woman ahead of me at the deli on Waverly Place ordered it that way and it just seemed right. There were no Starbucks on every corner yet, no singles or doubles or triples, no blended drinks, no soy. Only delis and trucks. Everybody got their coffees in the same places. We weren’t so divided back then. Hung up. The guys at those trucks and delis were good, too. They learned your order, spotted you coming a block away, and had your beverage wrapped in a paper bag so you never lost your stride as you hit their station.

I had my stride that day and continued to have it for quite some time after that. The fevered pitch of film productions, the possibility of fun and romance, sexual encounters, mystical conversations, all the action and excitement of the Village, the silly search for fame through all those separations. There was a way I walked on that day — my head held high, eyes sparkling under nice dark frames (l.a. Eyeworks), mind focused on all the promises of the future. I can’t name the day when the pace slowed — when my head wasn’t held quite so high and my eyes showed ominous dark circles and my mind filled at moments with apprehension and dread. The day I became just a little less certain. But it happened.

I knew it happened because I could no longer walk down Mulberry Street or wind up flights of stairs in old tenement buildings. I did it once and had an episode of vertigo so severe that I had to sit on those dirty stairs with my head in my hands for longer than I’d care to admit. I would no longer take walks by the Lincoln Tunnel or flip through the pages of fashion magazines. Bryce Canyon and deserts became off-limits to me. Always. Who needs to dangle in such spare places? Suburban homes and the appearance of sweet treats on Formica counters can create a reaction in me like fingers on a chalkboard in a schoolroom. It’s not that I don’t like these sights and sounds, these scenes, only that they activate a channel in my brain that cancels out all the others. Sensory overload, memory, the mystery and magic of the flashback cut.

The answer to the meaning of life may just exist in the flashback cut, but don’t ask me how to explain it. I can’t. I can only offer that looking backward, recreating our pasts, has a humbling way of putting things in their proper place. But you have to really look back. You have to work for it, every day, your eyes wide open. Study the footage. Not just the good shots either, but the outtakes, the mistakes, the blurry frames. What was going on? And why?

You may have to run away from what you discover for a while. Then come back to it. You’ll keep coming back to it again and again. You’ll be relentless because there is a prize, perhaps the only real prize we receive in this life, and it only comes after a very long while, if ever at all. A very personal understanding of who you are and why you are here.

11.

There was one other thing I would not do during those first years out, if I could help it, and that was walk into that building at 721 Broadway.

When they screened my first feature film there, many years after graduation, I did have to step inside. As I entered the lobby, I saw Lilly dashing for an elevator.

She did not see me and I did not make any effort to go up to her to say hello. The elevator doors quickly closed, and she was off to one of the upper floors of NYU. She is an adjunct faculty member now, training new students in the art and technology of the edit. She teaches them that good editing is like good sex — you are always setting up an expectation that the audience doesn’t even know it has, and then fulfilling it. She teaches them about Walter Murch’s hierarchy of reasons for cutting. She teaches them about certain sequences in Bonnie and Clyde.She teaches them to kill their darlings. I know that this is what she teaches them because this is what she taught me.

Another thing she teaches them, what she teaches them without knowing she is teaching them, is that time is something that can always be altered. This is not true, but in the world of moviemaking, it is a belief that is often held high.

**************************************************************************************

Michael Hess’s work has appeared in journals such as Malahat Review, Shenandoah, Grain, and Sport Literate. His essay “What Do You Wear to a Nudist Colony?” was included in The Best Gay Stories 2016 (Lethe Press).

A three-time finalist for the Iowa Review award in nonfiction, he has also been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and longlisted for the 2018 CBC Nonfiction Prize.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in ImageOutWrite,a publication of the Rochester LGBT Film Festival (Volume 5).