Childhood fears swell into adult insecurities. A rulebook.

“There is something attractive in the intense itch, something satisfying in the scratching that I cannot resist. I know this makes it worse, makes it last longer, but sometimes, I can’t stop, can’t help it.”

This feature is available, in slightly different format, on Medium.

–

Midge’s Bite

Rule number 1: I am not a doll; when pinched, I ache. Do not pinch me.

In my backyard, where I have built a suburban paradise: a pool in the center, landscaped with flowers of all colors that fill the yard with beautiful change throughout the spring, summer, and fall; where, too, I have installed an umbrella-shielded bar, several patio tables, each also umbrella-ed, and lounge chairs so that on any given day or evening whomever I invite can choose a setting. The food and drink will be rich and the platters lush.

This paradise is built as a response to deprivation. What I was denied by my parents I have provided myself. It is here I have also, by process of elimination, discovered that the biting midge thrives.

The biting midge is not so easily eradicated as the common mosquito. It has a hard exoskeleton, like an ant, so when swatted or slapped or occasionally hit with a flip-flop, it often takes the hit and emerges stronger, seemingly angrier, with a vengeful focus on the body of its desired prey. Midges fly. They love water. In fact, they are attracted by its glistening. Their bite is brutal, multipronged; leaving, after a painful pinch, missing flesh and a small, raised welt.

Most times, I feel the pinch, but on some occasions, I don’t feel it; only later do I know, when the welt emerges, one has chewed me. The welt increases on day two, forms a scab, and continues to increase in diameter on day three. The area surrounding the welt heats on day four. I have, I discovered, a painful allergic response.

The biting midge is my enemy. This is the version referred to as the no-see-um.

Rule number 2: Do not judge me for my possessions, as you enjoy them as much as I do.

I remember the summer I got a Midge doll. Due to my mother’s upcoming prison sentence for embezzlement — a fact about which my family believed I did not know — my father and mother ferried us to a vacant house in Monticello, New York, about an hour and a half and a world away from where I grew up in the Bronx. I was eleven years old, freckle-faced, pale skinned, with a ponytail my mother often fastened so tightly that I felt my skin pull.

In this old house, my family: my mom, dad, sister and brother and I. We waited for her departure. My Barbie and all of her worldly goods were back at home in the Bronx, or so I thought. I did not know then that everything we’d owned, all of our clothes and toys, our childhood pictures, the objects that made up our family’s assets, were being boxed and held somewhere as if we were, one day, all going to go home. I still don’t know where our goods wound up, only that I never saw them again.

To appease me, my mom bought me Midge from a small toy store in Monticello. Barbie’s best friend came in a coffinlike box like the one Barbie arrived in, but she wasn’t Barbie. She wasn’t as beautiful. Her eyes wider and a lighter shade of blue, her lips delicate and wide, she wasn’t the one I wanted. Had I known that I would never hold my own Barbie again, I would never have accepted her “other.” But then I thought when I got back to her, Barbie would need a friend.

That was the summer after fifth grade. Truth be told, and for once I’ll tell it, I was happy for the escape from the Bronx. My fifth-grade teacher, Mrs. Pearl — a beautiful Jackie Kennedy wannabe — hated me, a fact I could not put aside. She was the one who told us that our president had been shot, crying as she re-entered the classroom after the crisp voice of our principal, Mrs. Atkins, commanded via the intercom that all teachers leave their classes at once.

This was the year when I became aware (or wrongly believed) that sleeveless tops revealed my soul. My mother loved sleeveless clothing through all seasons. She often dressed me that way, too. I think that’s why I never paid attention in Mrs. Pearl’s class. I was too exposed, too aware that my naked arms made me visible. Mrs. Pearl looked at me with loathing. I thought I noticed her eyes fall to my arms every time she talked to me.

Once, the most popular boy in her class, the David who made Mrs. Pearl giddy, turned in his book report on Exodus(He is exceptional, she told us). His book report was written in the form of a play. Mrs. Pearl was so impressed that she determined we would perform it as a class at the end of the year. Of course, David would play the lead, but when he chose me to play Karen, his love interest, Mrs. Pearl, almost involuntarily blurted out, “What? Her?”

Rule number 3: Never sabotage my diet.

I’m going to gloss here over the earlier acquisition of my first and only Barbie. How the box arrived via UPS, the box so large that I had to practically dive into it, how my mother had bought it on her lunch hour and had it delivered because she bought not only the doll but also most of the outfits in the small booklet that came with Barbie. How it felt to hold her, and to look into her smoky, black-eye-lined eyes that never made contact, but looked down at me. I embodied her. And I won’t talk about the myriad ways that Barbie, and many of my other childhood goods — the ones that gave me confidence — were purchased with stolen money.

But I will say, Barbie was the ideal. To be her, to occupy her seat of power, is something I aspired to. I have come to believe that most of my friends felt this way, too.

How many of us learn to be friends as if we are Midge, born to a world that says we are the supporting cast in dramas unfolding; born, however, into real bodies that feel, souls isolated in flesh, bodies attached to souls crushed at the weight of engagement with other women? We are all Midge, Barbie wannabes. I know I am. When your mother goes to prison, forcing you to leave a comfortable life — your home, your things, and your wardrobe — leaving you with rags that no longer fit, and you must appear in school that way, it’s a scar. You lose more than the place you live, the people you love, and the goods you own; you lose, too, your purchase on a certain future.

And it is because I understand that many of my dearest friends are born with this sadness even if they don’t have quite the same exactitude in motivation as I, I have excused so many bad behaviors. I have understood the fuck out of them, tolerated to distraction deeds excused by their insecurities or their envy.

What happens when Midge finally has enough?

Rule number 4: Never tell me what other people have said about me without expecting me to ask what you said to defend me. Or what you said that made them think it was okay to gossip.

I am, at this very moment, withdrawing from many of my friends. In fact, it has been an ongoing process for me, figuring out who has pissed me off lately. I have never been in thisplace, however, this place where I really just want to be alone, away from friends — not one at a time, but all of them at once. I wonder, Is this the very nature of the suburban life I thought I needed?

Maybe I am not now, nor ever was, completely suited to this comfort. But I don’t know how that can be. This backyard, this house, is beautiful and sustaining to me. And then, finally, one day, sitting alone at the bar in the backyard, studying the shifting blues of the pool water as the sun drops low in the sky near to the farthest point at the corner of the fence, a glass of Chardonnay only just sipped, I decide I need a new set of rules.

I will call them The Rules for Being Midge’s Friend.

Rule number 5: Never tell me who is threatened by me, who hates me, who has done damage to me, because that also tells me you have allowed that space, just as the male dog pisses a mark to ward off competition with his scent.

I admit I was a strange child. I talked to myself. Not uncommon, I know, but I was two (at least two) distinct people. One was the sober, serious me, the one who knew I thought too much, too deeply; who knew that most kids my age were playful, happy to just be. Not me. I loved reading the world: the beauty of it all, the oddness of my parents, things that didn’t fit, the cruelty, the ways in which the understanding of math trumped language, the ways in which penmanship trumped grammar. I understood my parents’ weaknesses but cared more about the grandeur of their provisions. Their quirky Bronx accents. The incongruous accident of having them both as parents: my mother second-generation from Jewish Galicia, my father from Ashkenazi Russian immigrants. My mother all flash and sequined dresses. My father an aspirational low-level mobster with olive skin.

The odd thing was not them; they fit in the Bronx. It was me. I was supposed to be ethical. I was shy, like a bug in a room, watching, hoping, waiting for a meal. I knew it was wrong to steal, to take what wasn’t yours, to harm people with words or actions; my parents did not. I was a child of heaven; my parents were of Earth.

Once, my mother threw a high-heeled shoe at my father. He had cheated on her. The heel hit him square in the back of his head. I knew that was wrong. But I was so glad she had done it. Because in the end, it was he who left her. He moved in with my stepmother while my mother was in prison. He told her he was leaving her on the day she was released. I found out when I saw my future stepmother’s robe hanging on the door of his bathroom in an apartment he’d rented; before seeing the robe, I’d thought the apartment was for all of us, for when my mother returned. Still, knowing about his transgression, I always sided with him.

Rule number 6: You are not entitled to know my secrets. Ask me any question once. If I fail to answer or if I deflect, the answer is not for you to know.

It must have been when I was in fourth grade, before Mrs. Pearl, before I knew the end of my family was coming. I was wearing a brown outfit. The skirt was pleated, the blouse plaid and tucked just right. I had knee-high ribbed socks that came to just the right area below my knee, and my shoes were buckled brown loafers. I felt confident. I walked to school without worry that I was being seen; I read thoughts in others all the time, and I believed then that others could read mine.

The mature me noted the pride in my step, knew that I was thinking we’d move to the suburbs soon, just like our cousins; the only question, Would we move to Jersey or Long Island? The mature me worried for the me that was taking my part on Earth, that I was counting up my worth based on what I wore, what I owned, and, in particular, the gold star of David that my grandparents placed around my neck.

I told myself important things: You are changing. You are becoming one of them. You will grow up. But you must never tell our secrets. Don’t reveal who you have loved. Don’t share your fantasies or how you sate them, nor your fears and the processes of mitigation. You will be tempted to join them, to be like them, to trade secrets so that they like you. You will feel like mocking the child you are now. You will explain how cute you were. Don’t. Don’t betray. Because you will crush the child inside. And you will demean her for knowing that fantasies keep us grasping for a future.

From that time on, there was always a distinction between the she of better character and my self, the one with the tendency to divulge too much in order to fit in and then to bite.

Rule number 7: Never assume anything I tell you about someone I love in the spirit of complaint is yours to judge or share. Never share my complaint about a friend with anyone who will use that complaint to harm.

We have a backyard party with friends, dear ones, the kind of friends who, when you live so far from family, become family. I have had over the years many of these. Some are coupled, some not. I am serially monogamous with friends for the most part. But, often, I back away from friends as the environments become toxic. I back away to a more pleasant, more sustaining environment.

At this party we have our “couple friends” and my elder son and his partner, a beautiful young woman with almond eyes and long brown hair. We eat not at any of the serving stations, though all of the umbrellas are opened for effect. We eat instead, swimming floating, or standingin the pool. Scallops wrapped in bacon skewered for easy grip on a melamine platter meant to look like ceramic. Wraps of lettuce and veggies on another.

The sun blazes high and then moves to the west, skirting the magnolia tree, so until late in the evening there is no shade.

It is a beautiful day. And we have so much good wine. And then my son’s partner, herself a few sheets to the wind (though the day is still), meets me in the kitchen, where she sobs on my shoulder and tells me, “He’s going to leave me.”

I reassure her. “No, he won’t.” Calming her takes time. And at the end of the exchange, as I go back out with a fresh bottle of pinot, the sun has left; the dim cast before nightfall brings out the biting pests.

My friend tells me, “We have a service. They take care of mosquitoes. Try them.”

I do. Believing the problem may be mosquitoes, I try them. Even though I know with certainty centered inside me that she is saying, I make better choices.

Rule number 8: I am not perfect, nor are you. We teach in friendship what we need. Sometimes we are incompatible and we part. It’s always temporal, even if it’s not temporary.

Mosquitoes, as it turns out, are fairly easy to eradicate, I am told by the service. They do not travel far. If we can stop the life cycle within a perimeter, and control unchlorinated standing water, they can be eliminated.

Rule number 9: Giving things or meals or gifts or attention must be reciprocated by love, not necessarily equivalent meals or gifts or attention.

I was the ethical child outside of the family. So respectful of others it was as if, unless you were a close friend, I had no will. Completely submissive: Might I have been a dog in an earlier life?

But at home, I was playful and, I confess, increasingly cruel to my brother. I didn’t intend to be, but he was two years younger. And very annoying. My father, from the time Michael was four, expressed disappointment in his manhood, but that’s another story.

It is the story, for me, of the manufacture of a Ken doll. Each and every time my father was with my brother, there was a grave dig at his weakness. When my own son James was two, my brother long disconnected from my father, my father told me of James, “He’s a good boy, but he’s not a sissy.” How could I not hear all he was saying about Michael?

At first it was either accident or prank. I was six, he four; we raced to turn off the television after my father said the one who gets there first wins. What we would win (Was there a prize beyond his affection?) is now unclear. Michael was ahead of me, just reaching for the television, and so I pushed him, just a light shove on his back. I so wanted to win. His forehead caught the corner of the blond wood cabinet. He bled. I won.

We drew in coloring books at the top of a staircase, at a small table built for children to do this very thing. His chair tipped back. He bounced on each step. I could not help laughing. He looked so funny, the fear on his face a mask I’d recognized. Is it evil to laugh if something is so funny?

He set fire to the living room. He set fire to our bedroom chifforobe. I had to suffer the questioning of my parents when I had absolutely nothing to do with it. I was justified in my annoyance.

Rule number 10: Never tell me a lie that you know I see through and make me, in my loyalty to you, complicit.

And then there was the Sucrets box. It was a metal tin with a slip of paper and tangy, bitter lozenges to be taken for cough. When it was empty, I wanted it. I could put my little troll doll in it. (This was before Barbie.) Or money where I could hide it from Michael.

Michael wanted it, too, to keep money in. My father called Michael the miser because he loved money so much.

The tin was in his hand. It was opened. His fingers held the bottom, his thumb below the lid .I grabbed it with his hand still gripping, and as he tried to draw it to him, I pressed down — enclosing his thumb, meaning to hurt him, angry that he would try to take it from me. His eyes grew large, and then his face contorted. Blood oozed from his thumb onto my hand. It was the first time I had drawn it deliberately, though the shock of the actual wound, a deep cut almost to the bone, remains in my memory.

Every time since, when I cut myself in the accidental failed attempts at enacting some task — a razor blade that slips as I remove a sticker, a knife missing its mark on a vegetable, a window closed without attention for a finger — every time I explore my wounds, I remember this first deliberate act, how close skin is to flesh, flesh to bone, how easily the body breaks, how shallow the puncture and deep the wound.

Rule number 11: When you are late, I amuse myself as I break a pact of friendship to me. You have no right to expect that. Expecting me to wait means you want me to shake my own hand in agreement that you matter more than I do. You may show up breathless and sorry, laughing off your lack of planning; but what I’vedone to me in silent conspiracy cannot so easily be forgiven. When I wait, I get annoyed with you. But I hate me.

After the exterminators come to cloud the perimeter of our property with cedar oil (the organic choice), it seems that the mosquitoes were gone. And the gross but non-biting stinkbugs are gone, as well. Their large bodies no longer drop from the umbrellas as we open them, and I am so glad. For a while we can sit outside through day to dusk to nightfall without the hideous welts and intense week of itching that used to follow.

But this respite is short-lived.

I call our service and tell them, “It’s not working.”

“Hmmm … We can come back and re-treat. But mosquitoes don’t fly very far to bite you.”

Only later do we learn we have not only mosquitoes but also midges.

Rule number 12: If you are genuinely concerned for me, enough to reveal what I have not released, you must be sure the person with whom you share my secrets actually cares for my welfare.

Once I went with my father and stepmother to visit my father’s sister at her home in New Jersey. My brother and sister were there too. They were young and single at the time; I already had my daughter. All the cousins were there, living their bon vivant lives, laughing, eating, splashing in the pool.

My father sat with my stepmother, both of them chain-smoking. She’d pull in the toxin-filled smoke deeply from the cigarette centered in her mouth until her cheeks sank, and then she’d hold her breath, her eyes rolling a bit as she savored, before she’d exhale. My father drew smoke from the side of his mouth, then exhaled quickly. He’d flick the ash with his middle finger over and over; then when the cigarette was spent, he’d take a final drag, wince at the heat, and flick away the butt. So cool.

And my stepmother sat and watched all of the action, speaking only when spoken to by anyone other than my father. She was his protector, his coach, his guide, a witness to his benevolence — a trait only she could see. He once told me, “She doesn’t need to go to church. She’s good. Not like your fucking mother.”

All the cousins dove or jumped into the pool, my sister and brother too. I did not. Though I probably weighed ninety pounds, I felt fat, worried my father would look not at my weight but at my chicken skin, the raised bumps on my thighs like a kind of acne.

So I sat with him and her as everyone else played and ate, filling large plates and leaving them everywhere. I ate only one piece of chicken, afraid of carbs and also that my father would see me and chastise me for gluttony. I sat until my aunt began the early job of gathering some of the plates, loading them into a white plastic bag.

My father, mid-cigarette, looked at me. “Get off your fat ass and help your aunt clean up. Who raised you?”

My stepmother said nothing.

Rule number 13: Never tell others my secrets via feigned concern as you garner new friendships. I share my friends but never my friendships.

My elder son does leave his partner, though it was almost a year and a half after she tells me she knows he will. The two women before her were beyond troubled, angry to the point of abuse toward him. His partner was simply unsure. Was she ready to marry, to have a child, to give up holidays with her family in order to share them with ours?

My son was more than ready to comply with the cultural scripts, or so he says. She, a fence sitter — he left her stunned. Within a month, there is another angry woman, another breakup — easier, though, without the long history.

He loses a dog. He misses his dog. He gets a motorcycle. He’s now a self-described liberally-inclined-politically moderate-biker who also happens to be single. And, most days, he is my friend.

Rule number 14: Never tell me you screened my call and decided it was best for you not to talk right then. It presupposes that what I had to say was not important enough for you to attend, and it says you offer contingent alliance, not friendship.

I want to go to a street fair. There is one a few miles away. All of the friends I am willing to go with live too far away or have other plans. I do not want to see the ones who live close.

I call my older son. He will take me to the street fair on a beautiful July afternoon. “I’ll drive,” I say.

“Wanna ride the bike?”

“No.”

“Come on. Live a little.”

“Live longer,” I say.

Sometimes I love being with him. His voice has grown to the same pitch and timber as my brother, Michael’s. So often when we are spending long days together, at the beach or on car rides, or, on a day like this, when he speaks, I feel, emerging from his tone, a sense memory that provokes my guilt. He is my son, so I must be attentive, must be kind, must protect without pretense his manhood. He is not me. He is not my father. He is not my brother. And I will not craft a Ken doll.

The first booth we stop at houses two woodworkers and their wares: one is a man who carves and paints custom signs, a fast-tawking Lawng Islinda. The other is a wooden-sign painter, mostly flags. He finishes the pieces with a heavy gloss of polyurethane. He speaks in Irish brogue.

The carver sees my son’s T-shirt has a fireman’s emblem. They share life histories. The carver left Long Island after 9/11/2001. He lost too many friends. My son listens, has no intention of revealing his own story — he lost his sister, my only daughter, that day, and his future niece or nephew, the one she carried. My son withholds this detail. But I share it, and he, my son, moves his body closer to my own, without holding me, without putting an arm around me. He moves closer so that his side, his arms folded in front of him, touches my side. We are bound in this way. He wants to be my father, I think. Or afather.

The former fireman, now wood carver, expresses his sorrow, and we move on. Another tent with jewelry. Yet another with baskets and peanut brittle, the proprietor a man of color. I ask my son if he’d like some brittle. He says no, then yes. But we walk on because there is a long line.

We walk until we find a tent from a local bookseller. I know one of the two women talking conspiratorially behind stacks of books. One of the books is a journal where one of my essays is published. I am happy to see her. I expect her to be happy to see me. She is not.

“Margaret?” I ask, as if I don’t know it’s her.

She turns to me, nods to my son, then says, “Hi” — but then as if she has just recognized me: “Oh, hello. How are you? What’s new?”

Is there a pull back as she asks, as if she doesn’t really want to know? I read that there is. She is distant.

“Nothing’s new,” I say, though I want to tell her that I’ve completed three essays this past week. I want to tell her, but I don’t because I wonder what she’ll do with the info and truly I don’t want to inspire spite.

“How about you?” I ask.

“The usual — writing, writing, writing.” Then, “Oh, by the way, this is the author…”and she names her as if I am supposed to respond with instant recognition.

We shake hands. The author moves her body back in the chair as I extend my hand. Though she must look up to meet my gaze, she manages to look down, too, with the slight curl of her lip (clearly not a smile, though she could argue it is) and a penetrating gaze.

“You mustbuy her book! You needher book,” Margaret says. I pick it up. The title is bold, misogynist, I think. I turn it over to read the blurb. It’s a mystery about some crimes women have committed against one another.

“Is it a mystery?” I ask.

The author nods.

Margaret presses: “She’ll even autograph it!”

I am out in the world. I’m the submissive. I remember this as I rest the book back on its stand.

My son is at my side, taking it in.

“Maybe when we swing back around,” I say.

We move on.

Two booths down, my son asks, “You do know they’re still talking about you?”

I am impressed that he reads Margaret’s judgment in the same way I do. Is this validation of me? Should I be happy or have I shared my paranoia?

Rule number 15: My family’s secrets, their stories, are mine to tell and share. You never have the right to share what you’ve gleaned through proximity to me.

The day after the extermination service comes and sprays the life out of my property (I mean, literally, a fog assault on all of the vegetation with heavy duty chemicals) I pull out my floatie and navigate into the soft blue water.

Within minutes, I see the first midge. I slam her with my hand (turns out, it’s only the female that bites), so fiercely my palm smarts as it hits the water. They get me three times, one of them on my face. That’s how I know — these are not mosquitoes. These are something worse.

Because it is on my face, I do not scratch that one. I want to minimize the chances that it will last long and leave an ugly scar. The ones on my arms and legs, though, I tend to fetishize these. I scratch around the bites, drawing the venom, calling it to flame.

There is something attractive in the intense itch, something satisfying in the scratching that I cannot resist. I know this makes it worse, makes it last longer, but sometimes, I can’t stop, can’t help it.

And what I discover from not touching the one on my face — leaving an insult be really does make it less painful.

But I can’tleave them be.

Rule number 16: I may leave you for a while when I feel a trespass against me. I will be back unless you have done harm to my family. And then it may take much longer.

Over the course of my life I have had many friends. I’ve enjoyed most of them for a time, until, because I hear so deeply words that wound, I back away. I’ve often wondered how others negotiate a friendship going stale or angry. Does it happen to everyone? Do they back away as I do? Or do they let the slings, the slights, the petty competitions roll off?

I worry, in particular, whether I have spread this tendency to my sons. Do they see every slight? Take it to heart too closely? Will they ever be settled? Or will they, like me, be ever in wait for the final blow — always, in the end, wondering how to balance a life lived in shared spaces with the desire to stay above it or away from it all?

Rule number 17: I am not you. I do not have to be like you to care for you. I will never be you to win your love.

My sister, Robin, comes up for a long visit with her two daughters, Laura and Steph, and Laura’s eleven month-old baby, Elle. They come to swim. We spend five days in the backyard, mostly in the pool. And, unusual as it sounds, Laura and Steph get along for the most part. Not much sniping at each other.

Baby Elle (my Mini Me, is how I think of her) seems to tap into a lot of our family’s negative energies. At eleven months, the world has not yet robbed her of her instincts. She is smart, cagey, and laughs quickly. I watch her in the pool. She favors her father. I see him in her face.

I also see my mother’s absence. No one except for me looks like her.

Before my mother decided to submit to dialysis (a treatment that extended her life by only a couple of years) I said, “It’s your choice, Mom: a few more weddings, births, graduations. You in or out?”

Laura gets out of the pool, handing off Elle to Steph, and as Laura drags a towel over her wet body, she lets out a yelp. “Shit! What the hell was that? Something pinched me!”

“Crap, it’s those biting bugs again,” I say.

Later that night, Laura lets me look at her welt, a slight bump with two distinct dots. But I have at least three, one a long line on my arm. And, as it turns out, I am the only one to respond with three days of agony.

Rule number 18: We all have rules. Don’t judge me by yours without trying to understand mine.

Sometimes I can’t sleep. Because in my attempts to fit into this land of plenty, I worry that I have won a competition against a friend, and I worry about the blowback. Or I worry that I’ve harmed someone with my sharp tongue, my thoughtless wit, my feeble insecurities that allow me to see their vulnerabilities before I’ve have the time to control my own. Have I walked away from too many people? Have I taught my sons to feel wounds they might otherwise have missed? Will my legacy be what I’ve crafted in my life — a land of abject aloneness?

But then morning comes, and I remember again the slights, the aspects of friendships I cannot abide. And I want my revenge or my distance.

Rule number 19: You can never be as good a friend to me as I am to myself. I make that unbreakable pact to the child I still am.

As my son and I are wrapping up our day at the street fair, he notices a stand with what look like African drums. In various sizes and in varied patterns, they hang on small shelves, carved wooden tubes that narrow in the center, where a leather slot covers an opening. Inside a leather slot on one of the pieces is an iPhone. Music fills the tent. I continue three stands down, until I notice my son was no longer at my side. I double back to find him.

My son has one of the wooden tubes in his hand. “This is so cool. It’s a speaker. You put your phone in and the wood amplifies the sound.”

“Or,” the seller offers, “you talk to your momma on the phone and attend to your business.”

I buy it for him, even though it turns out the proprietor is from Atlanta, a Falcons fan. I root only for the Saints.

Rule number 20: Do not, do not ever, disparage people I love and expect me to concur. I hear everything. Even when you speak in code.

I give up. There is no way to eradicate from my yard the biting midge. They are a feature of the world if I am to swim. I can pray they don’t nail me, try to apply bug repellent; but, in the end, they are there in the flowers. They love the nectar of the beautiful roses and lilies.

So I go out less. See the beauty, too, in rainy days. And sometimes I think about moving away.

This worries my husband immensely.

Rule number 21: I am a teacher and so I learn all the time. Teach me only about you, about your borders. I will respect that even if you don’t know you’ve calibrated yet.

After we buy the wooden amplifier, on our way back, money and energy for the day spent, my son, still wondering about the bookseller, asks, “What makes women like them act that way? Does it bother you?”

“Not anymore.”

“Really?”

“It’s like Barbie and Midge.”

“The dolls?”

“Everyone wants to be Barbie, and the only way to get there is not to be Midge.”

“Women always do this judgment thing,” he says with certainty. “I’ll never understand them.”

“No,” I correct him. “It’s the way everything works. All power dynamics. There ain’t no Barbie. We’re all Midge just trying to be Barbie.”

He accepts this. Ponders it. Wraps his arm around me as we head back to the car. We are on the final street, but I say, “Let’s go back the way we came.”

And we do. We double back. But when we are across from the bookseller, an old neighbor in a baseball cap appears. We miss him. He is also a Saints fan, I remember, has taken his sons down to NOLA to help rebuild after Katrina. He is a part of Southern comfort.

We greet each other with hugs. We are right in front of the bookseller. I have my side to the stand. The neighbor tells us his wife is a few stalls ahead with his grandchildren.

“Oh,” I say. “I don’t have any yet.” And I look at my son. He smiles. If he feels anything more than my poke, it doesn’t register on his face.

“Soon?” the neighbor asks.

“Ask him.”

“I just have to find someone who can stand me,” my son says, and I look at his face, his movie-star face with the same dimples his sister had, only higher on his cheeks.

She, too, wanted a child. She, too, wanted a marriage. And right then and there, in the mass of people going in one direction or another, I miss my own mother. I miss the way she would always pay for everything we bought when we were together, the way I never had to thank her — that no one ever really did, that she would have moved heaven and earth to provide for us. That she knew what it was to be left alone, and that she never cried.

Rule number 22): When it is so clear that the rules as written suck, I will craft my own.

Once, I remember, my father was a father. I was pregnant at seventeen and unmarried. His family, sister, and brother thought it best for me to abort. I did not. It was 1971.

I believe it was my stepmother who made my father support me as the family argued. “She’s your daughter,” she told him.

I stayed with them for a while. My mother would call their apartment with envy dripping from her like chocolate on a sundae, an itch she loved to scratch: “Paradise in Hell. That son-of-a-bitch is living off the fat of the land.”

His neighbor asked him one day, “Who is that living with you?”

“It’s my kid. Her husband dumped her.”

I heard, from behind a door, my stepmother say, “Jack! That’s your daughter!”

Rule number 23: It may not be your choice that you are heterosexual, but it a choice to be heteronormative. Do not, do not ever, use your man’s words, his ideas, his value of you to compare your worth to my own, not by articulation direct nor inflection nor innuendo.

Through my peripheral vision I see the bookseller and the author watching. They notice I have doubled back. I turn my back. I want them to feel me notbuy the book.

I haven’t seen several friends in weeks. The reasons why bore me. I tease myself over their slights. Go back and forth over whether it matters, and how I might bear to just let things go. But something else, too: Why now? I have two sons. Have I made them lonely? Have I been a good mother? Though I have not enumerated the ways in which this is true, I had one — a good mother, the best mother for me.

I walk over to the window of my bedroom, the one that faces the street, where, because it is late afternoon, the sky still bright and blue, I can see the white fingernail of moon. I feel compelled to say out loud, to my father, gone twenty-seven years, “You were never a real father. Fuck you.”

Rule number 24: I am Midge.

It is a sunny day in the backyard and I am enticed by the warmth of the pool water. On my floatie, one comes from overhead, lands on the water. I am not prepared with a flip-flop in my hand. I am alone in the middle of the pool.

“Not this time, asshole!” I say as I find it on the surface of the water and use my thumb and index finger to pinch it, so hard that I rub it to some other form. Then I swirl my hand to clean it free of insect remains. And I know for certain one thing that will forever be true: Even if I eradicate every last one, I will still remember and stay on guard.

Rule number 25: I am Midge. Just Midge.

My son and I are at his car in the dark garage abutting the street fair. As we climb in and shut the doors, it gets darker. “Don’t worry,” he says, “that you didn’t buy the book.”

“Do you think I should have?”

“You wouldn’t have been able to pay for it. They’re too high up on their thrones for you to reach.” It’s not really animosity, more just the behavior of “coolness” that subjugates.

I am proud of him. I have told him this before and I will again later, but as he puts the car in reverse to back out of the space, I say, “The midge bites.”

He winks at me. Complicit. He is no Ken doll.

*********************************************************************************

Donna Lynn Marsh’s creative nonfiction has appeared in literary journals such as Red Savina Review, Corvus Review, Wrap Around South, and Rose Red Review. Other work has been published in The Guardian, The Huffington Post, and Smirking Chimp. “Midge’s Bite” is part of a planned book of linked essays entitled Barbie’s Dream House.

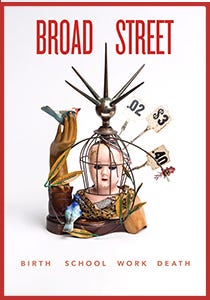

Gale Rothstein is an assemblage and collage artist who recently had a solo exhibition at the New York City firm FXCollaborative Architects. Her assemblages can be found on this issue’s cover and in a separate feature, “The Archaeology of Desire.”