“Where are we? Who is here with us? How big or small are we? Are we awake or dreaming?”

Editors’ Note

Gale Rothstein’s work embraces dualisms in a conflicted environment: impermanence and reinvention, loss and hope. She unearths, cuts apart, and reassembles objects in a never-ending exploration of the tiny drives that move us.

In the title piece for this feature, “The Archaeology of Desire,” a marble urn sits atop a box in which three human images are being made and remade: Against the backdrop of a male torso, one glass ampule spits out a manikin, which is in turn wired to another manikin still in its ampule. Within the finite wooden box, the process itself recedes into infinity, down past the etched wooden blocks and into the classical ruins evoked below. Wooden griffins bookend the experience, implying it’s finished — but the boundaries are more plastic than we might think; even a bookend loses its face and crumbles to dust. It’s Birth, School, Work, and Death in one taut three-dimensional image.

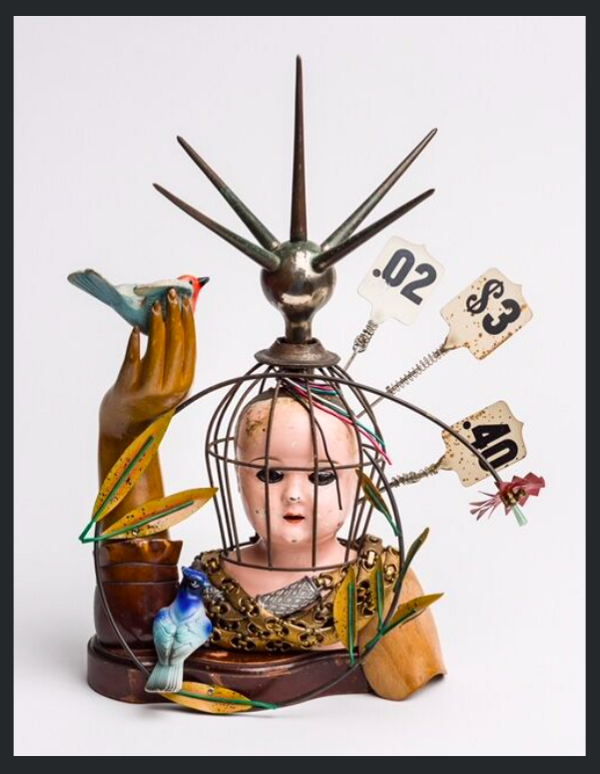

We chose “For What It’s Worth” for our cover because it, too, evokes change within a limited framework. And yes, there is a pun in that — change refers literally to the 2–3–4 sequence of numbers pulled from an old-fashioned cash register as well as to more metaphysical evolution. The doll’s body resembles a medieval saint’s reliquary, with a detached hand holding a tame bird; its head is trapped in a wire cage, but its Lady Liberty headdress stretches up toward the sky and through our magazine’s title.

Here’s what Gale’s work says to us: We may be limited by our circumstances, but we can use the detritus of our lives, and of the people who have gone before us, to make art.

That is very much what it’s all worth.

–

Artist’s Statement

By Gale Rothstein

My art practice has always been about “putting together the pieces.” When I was a child, it was not unusual for me to take apart one thing to make another.

Referenced through re-use, my work is informed by my lifelong interest in collecting antiques, collectibles, found objects, the harvested innards of discarded and broken appliances, hardware, and other salvaged objects. Re-contextualized and juxtaposed in discordant and surreal environments, these sculptures provoke the viewer to ask, “Where are we? Who is here with us? How big or small are we? Are we awake or dreaming?”

I parlayed my aesthetic into my first professional career, which was as a jewelry designer. Originally trained by a local silversmith in Tucson, Arizona, I returned to my native New York to hone my skills, working in many areas of the jewelry industry, including costume and high-end pieces.

In 1981, I opened Gale Rothstein Designs, Inc., in a studio in the Meat Packing District. There I designed and manufactured an extensive line of fashion jewelry for over two decades, employing several artisans. My pieces have been sold in hundreds of retail stores and craft galleries worldwide, and appeared in many fashion publications including Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Glamour, Women’s Wear Daily, and several industry magazines. Early pieces have been surfacing on vintage jewelry dealers’ websites for many years.

No longer producing jewelry, I currently create one-of-a kind collage and assemblage sculptures. These assembled boxes and environments (“Inter-Exteriors”) emerge from a strong narrative and historical framework that informs the choice of objects and the relationship of diverse elements to each other and the overall context of the composition. I consider object identity, form, color, and structure in composing the assemblages. Two-dimensional collaged backgrounds are carefully coordinated with the placement of the three-dimensional objects.

I dedicate my work to the memory of my father, Milton Rothstein, a jack-of-all-trades and one of the original recyclers and re-purposers, decades before it was a trend. I inherited his vintage collection of parts and incorporate many of his objects into my sculptures, further supporting the historical and personal foundation of the work.

My past creations include a crumbling amusement park, an abandoned bathroom consumed by nature, and a bedroom situated simultaneously inside a display room and on an Italian piazza. Passing through those environments, the visitor is challenged to reevaluate the sense of time, place and orientation. Themes addressed range from the core human experiences of regret, remorse, loss, and impermanence to reinvention, renewal, and hope.

Read on for Gale’s discussion of individual pieces.

— — — — —

“For What It’s Worth”

“For What It’s Worth” suggests uncertainty as it relates to concepts of value. The amounts on the vintage cash register flags are random and have no particular meaning, intended to express the subjective and arbitrariness of valuation. The figure is draped in ornate chains that simultaneously enhance but also bind her. I have included an understated visual clue to a popular saying referencing value and risk- “A bird in the hand is worth 2 in the bush.”

——

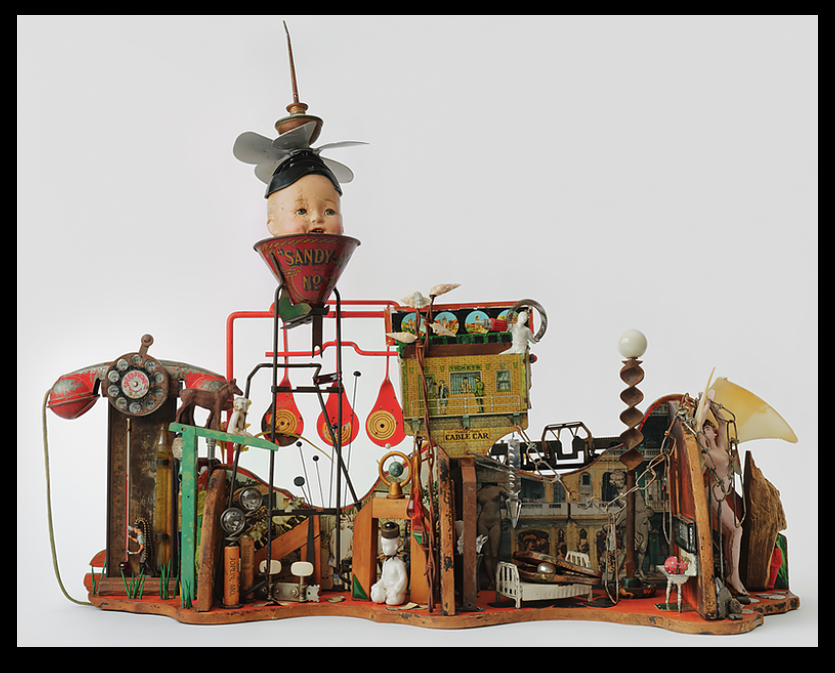

“She Dreams of Her Disappointing Life that Might Have Been Then Was”

This is one of the pieces from my Inter-Exteriors group. The work demonstrates the interconnectedness of the continuum of our experiences, with objects from each “room” overlapping and cascading into the next.

Further investigation finds small references to abandoned hopes: i.e., a child is on a slide to a dead end. An abandoned space that is simultaneously a bedroom and a kitchen is situated on an Italian piazza, evoking the improbable and the sense that we are in a dream. The dreamer herself is imprisoned by her own response to regret, failure, and remorse, which may be based on actual lived experience or on her subjective beliefs about the events of her life; hence “That Might Have Been Then Was.” This leads to the inherent question posed in this work: Real, imagined, perceived, at what juncture in our experiences have we concretized these perceptions of and opinions about our lives, such that we refer to them as memory?

— —

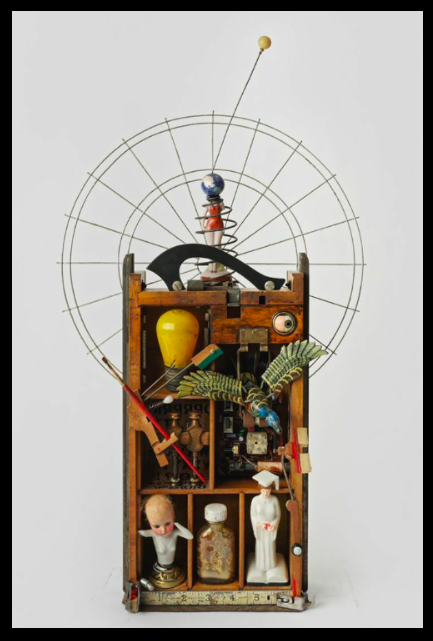

“The Measure of Success”

In this mechanized, monetized, commercialized world, we measure our success concretely and symbolically; how much gold ($) we have accumulated, art work we’ve acquired, degrees achieved and people “Friended.”

We compare ourselves mercilessly to others.

Don’t we know that we are the center of our own worlds within this infinite universe?