“She and the fire column in movement, she forward. It spins upward a hallucinatory dance…”

BROAD STREET presents the first installment of a series tracing Luanne Castle’s ancestry in poems and short prose — with photographs, newspaper clippings, and other source materials: the small things from which Luanne has pieced together family history.The poem itself can be downloaded and printed as a broadside, or scroll down read a plain-text version.

Click here to read Luanne’s introduction to the series.

This feature is also available, in a slightly different format, on Medium.

*****************

Above: Alice Paak with Alice Leuwenhoek, circa 1898.

*********************************************************************************************************

Drag this broadside to your desktop to print it out at home.

**********************************************************************************************

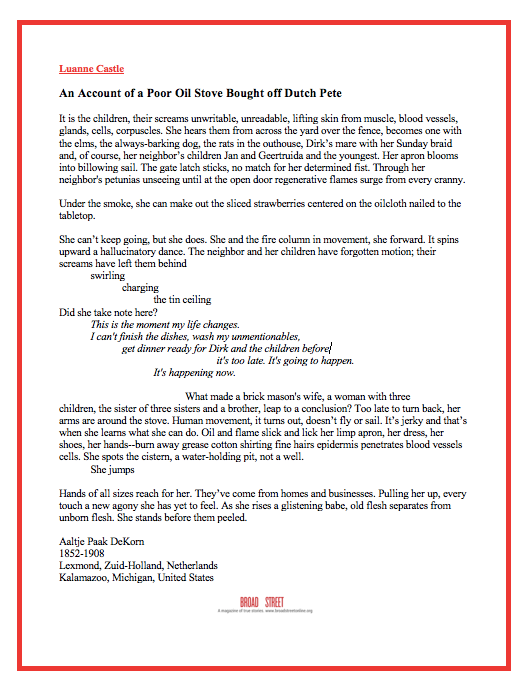

An Account of a Poor Oil Stove Bought off Dutch Pete

It is the children, their screams unwritable, unreadable, lifting skin from muscle, blood vessels, glands, cells, corpuscles. She hears them from across the yard over the fence, becomes one with the elms, the always-barking dog, the rats in the outhouse, Dirk’s mare with her Sunday braid and, of course, her neighbor’s children Jan and Geertruida and the youngest. Her apron blooms into billowing sail. The gate latch sticks, no match for her determined fist. Through her neighbor’s petunias unseeing until at the open door regenerative flames surge from every cranny.

Under the smoke, she can make out the sliced strawberries centered on the oilcloth nailed to the tabletop.

She can’t keep going, but she does. She and the fire column in movement, she forward. It spins upward a hallucinatory dance. The neighbor and her children have forgotten motion; their screams have left them behind.

swirling

charging

the tin ceiling

Did she take note here?

This is the moment my life changes.

I can’t finish the dishes, wash my unmentionables,

get dinner ready for Dirk and the children before

it’s too late. It’s going to happen.

It’s happening now.

What made a brick mason’s wife, a woman with three children, the sister of three sisters and a brother, leap to a conclusion? Too late to turn back, her arms are around the stove. Human movement, it turns out, doesn’t fly or sail. It’s jerky and that’s when she learns what she can do. Oil and flame slick and lick her limp apron, her dress, her shoes, her hands–burn away grease cotton shirting fine hairs epidermis penetrates blood vessels cells. She spots the cistern, a water-holding pit, not a well.

She jumps

Hands of all sizes reach for her. They’ve come from homes and businesses. Pulling her up, every touch a new agony she has yet to feel. As she rises a glistening babe, old flesh separates from unborn flesh. She stands before them peeled.

*********************************************************************************************************

Luanne reveals her sources

Alice Paak DeKorn

My great-great-grandmother, Alice Paak DeKorn, was born Aaltje Paak or Peek, in Lexmond, Zuid-Holland, Netherlands, on 9 September 1852. Her birth record is on file in the Netherlands. The last name was spelled Paak by Alice herself. It is also variously Peake, Peak, Paake, and Pake, which makes research difficult.

Studio portrait of Alice, circa 1890.

Alice’s mother, Jacoba, passed away when Alice was thirteen years old, and less than four years later she immigrated with her father, three sisters, and a brother to the United States. At the age of nineteen, she married a successful brick mason and contractor, Richard DeKorn, and together they had three children.

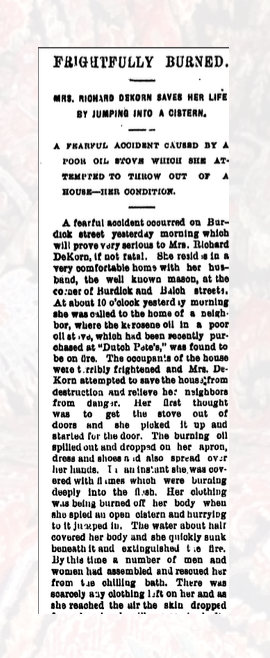

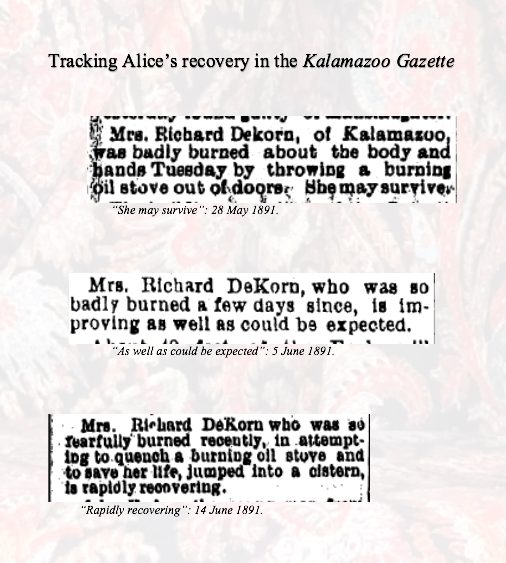

When the fire in the poem occurred, Alice was thirty-eight. Her daughters were in their late teens, and her son was ten years old. Alice almost died, but as the newspaper clippings show, she made a remarkable recovery.

She lived to age fifty-five, when she died of heart disease, five months before her grandson (and second grandchild), my grandfather, was born.

I never heard the story of the fire growing up. When I discovered the first newspaper article about it, I was stunned by Alice’s bravery and the fact that the family had not passed this information down to future generations.

Two heirlooms have come down to me from Alice: a shawl that she made herself (featured in the background of the newspaper clippings) and a family tree painted on a shell that she made for her daughter as a Christmas gift.

The shell shows me that she shared my interest in family history.

Dutch Pete

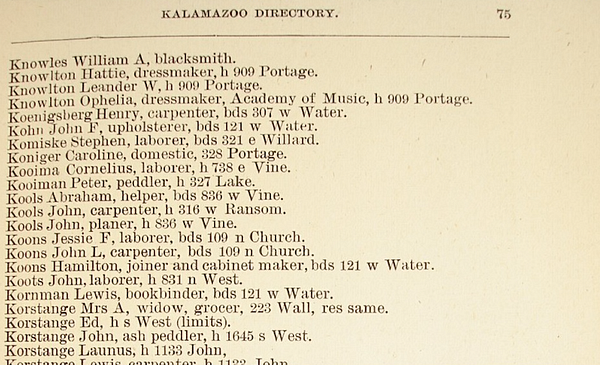

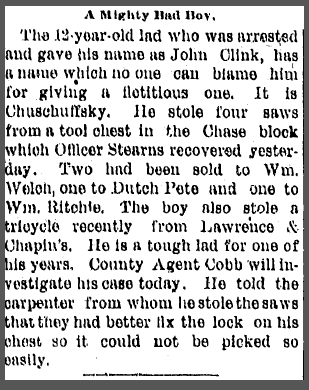

Dutch Pete’s history is also out there to be found, in city directory listings and brief mentions in the newspaper.

*********************************************************************************************************

Luanne Castle’s Kin Types (Finishing Line Press), a chapbook of poetry and flash nonfiction, was a finalist for the 2018 Eric Hoffer Award — and features a portrait of Alice on the cover.

Luanne’s first collection of poetry, Doll God, won the 2015 New Mexico – Arizona Book Award. Her poetry and prose have appeared in Copper Nickel, Verse Daily, Lunch Ticket, Grist, River Teeth, The Review Review, Phoebe, and other journals.

Alice’s shawl.