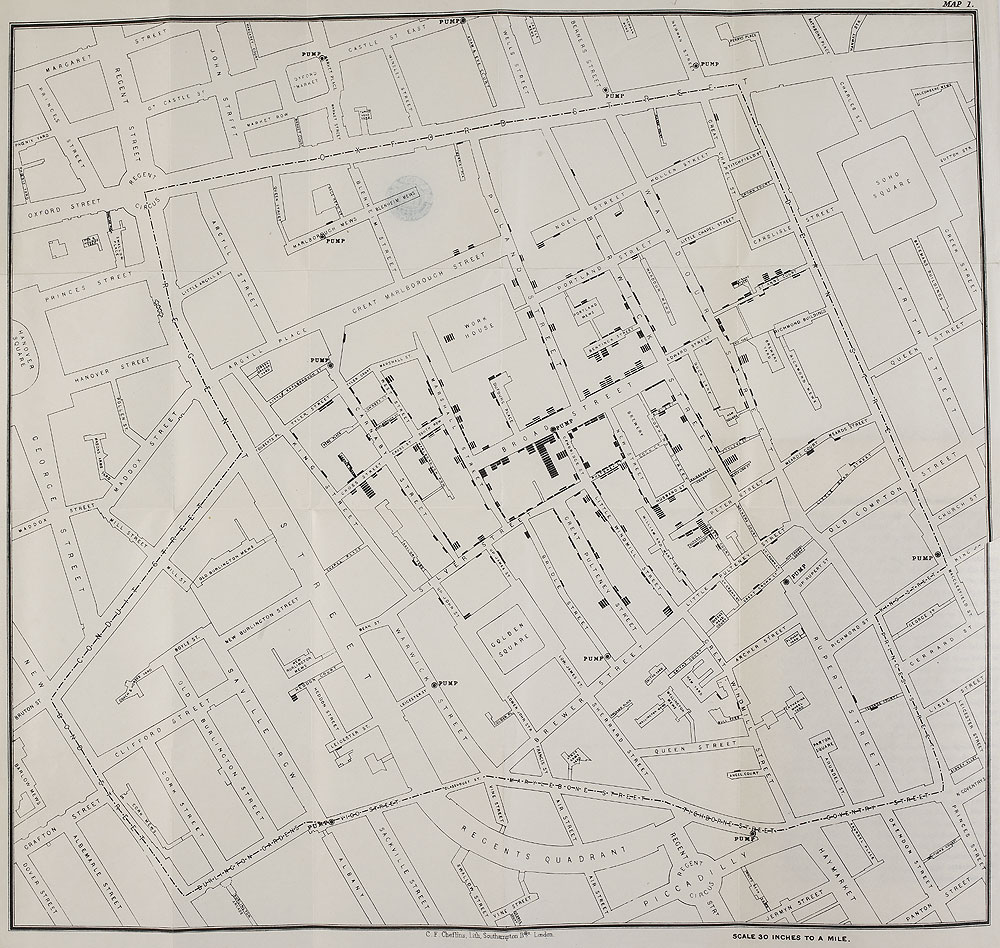

Map of Broad Street, London (by John Snow, all rights reserved by The British Library Board)

I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

Excerpt from “London,” by William Blake

This reflection on William Blake’s 1794 poem “London” raises the question: How often does the human instinct to discover become nullified by an apparent absence of mystery? Some might see what they see and decide: “It will always be as I see it and have seen it.” It’s not always easy to discern the real truth.

In the mid-1800s, cholera swept through the streets of London. To protect themselves, people had become accustomed to covering their mouths and noses with slips of cloth, because the general understanding was that the disease traveled by air, along with unpleasant odors. John Snow, who had begun his medical career as a surgeon’s apprentice at age 14, came to doubt this prevailing belief.

“The most terrible outbreak of cholera which ever occurred in this kingdom, is probably that which took place in Broad Street, Golden Square, and the adjoining streets, a few weeks ago. Within two hundred and fifty yard of the spot where Cambridge Street joins Broad Street, there were upwards of five hundred fatal attacks of cholera in ten days.”

—John Snow, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855

—John Snow, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855

During this cholera outbreak of 1854, Snow plotted on a map (above) each death caused by the disease. With this method, he was able to hunt down the cholera’s epicenter and revealed it to be the public water pump on Broad Street. Thousands of people used the pump, swiftly spreading the germs that cause cholera.

According to The British Library Board, removing the pump handle showed an immediate decline in cholera cases. The map, the experiment, and Snow’s report on it led the way to the science of epidemiology and a new understanding of disease. Snow shone light on a truth that had been in plain sight and yet a mystery, invisible and unseen.