by Jamal Stone

Contemporary art—art from the late 20th century to the present—often challenges preconceptions, stretching the boundaries of what is and is not art. But sometimes, definitions in the art world get too fuzzy—take, for instance, our understanding of art crime.

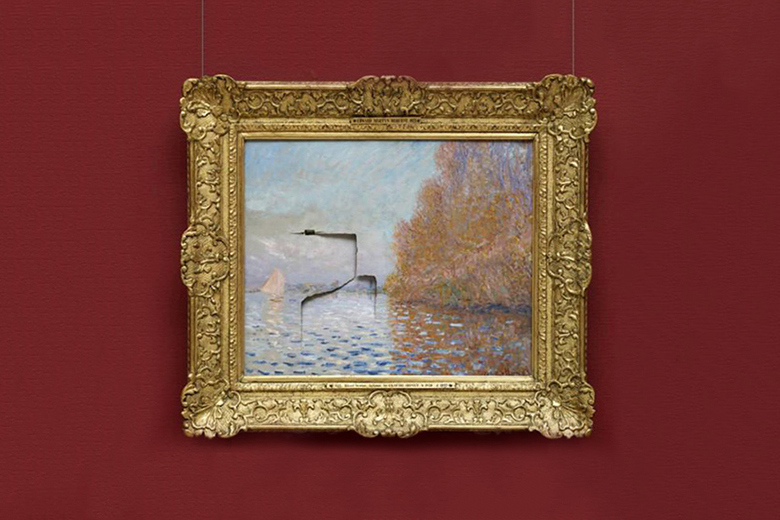

Traditionally, art crime is simply crime committed against art, used to describe larceny, forgery, or that half-crazed man that punched a hole clean-through a Monet (seen above). But is art crime simply crime against art, or does it include crimes committed in the service of art? In short, can the artists themselves be the criminals? Broad Street investigates contemporary art’s criminal side in this, the first of a three part series.

~/~/~

To begin, let’s take a seemingly cut-and-dried case. Early last year, one of Ai Weiwei’s priceless painted vases, on display at a museum in Miami, was smashed to bits by one Máximo Caminero. Clearly, it is against any and all social norms to grab a museum piece and destroy it, but it seems as if Caminero was inspired by the same artist he was acting against.

After all, Weiwei’s pièce de résistance, on display in the same room where Caminero’s crime was committed, is a series of three black-and-white photos in which the artist is shown holding, and subsequently dropping, the aforementioned vases. Weiwei’s initial artistry was itself an act of rebellion, as the vases date from the Han Dynasty, some 2,000 years ago. So Caminero, saying he was incensed by the museum’s lack of local art, acted out.

When reached for a comment, Ai Weiwei swiftly condemned the act, saying, without a hint of irony: “If [Caminero] really had a point, he should choose another way, because this will bring him trouble to destroy property that does not belong to him.” In a separate interview with the Miami New Times, Caminero was attuned to the absurdity of his case: “What [Ai Weiwei] did was wrong too. Ai Weiwei is breaking cultural patrimony.”

So who is right?

Strictly speaking, both Ai Weiwei and Máximo Caminero committed art crime, if that term includes defiling the work of another artist in an apparent sign of protest. But one is multi-millionaire Ai Weiwei, whose every move is imbued with cultural significance; the other is a struggling artist in Miami whose name was unknown until he stood in the shards of Weiwei’s pots. The definition of art crime is woefully ill-equipped to distinguish between the two.

The legal aspect of this case, at least, offers more insight. Since Weiwei owned the Han vases and urns, having brought them with him from China, his act of defiance may arguably have been culturally offensive, but it was legally protected.

Caminero, by contrast, did not claim (or have) any ownership over the vase he destroyed. In fact, when first approached by police and museum officials, Caminero admitted to presuming that the vases were replicas, and was stunned by their monetary value.

Still, political speech, even destructive political speech such as flag burning, is protected in the United States. That might explain why Máximo Caminero was let off easy with a couple of days of jail time, a benevolent $10,000 insurance fee, and one hundred hours of community service.

Unfortunately, adding the element of legality introduces its own set of questions. What exactly is being valued here? Ai Weiwei bought the urns and vases, now valued in the millions, for much less money than they now are appraised. By painting some and smashing others, Ai Weiwei ensured that these vases and urns are worth more now than they ever were.

Are we upset that Caminero smashed a vase from the Han Dynasty? That he broke museum taboo? Or that he destroyed one of Weiwei’s several painted vases? Even the legal definition, as official a measure that we can get, cannot escape the problem of artistic value—we slapped a number on the vase, and said it was worth millions, but why did we do that? Why are some artists measured in millions, and others in cents?

Perhaps Caminero’s notion of “cultural patrimony” is not so absurd. We laud the fathers of high art, even if their actions, like dropping some pottery, are everyday in isolation. Caminero is no hero, but his actions reveal the arbitrary nature of high art. For now, art may be broadly protected, but, just as the bounds defining art shift, so too can its legal limits.

[x]