When I “get in,” I am seeing, hearing, and smelling the world along with the characters… And so I say again, in the hope that my doing so will make the process a little less disheartening for beginning writers: Keep going, for if you keep going, the “real” or “true” story will reveal itself. And when that moment happens, the feeling is like no other.

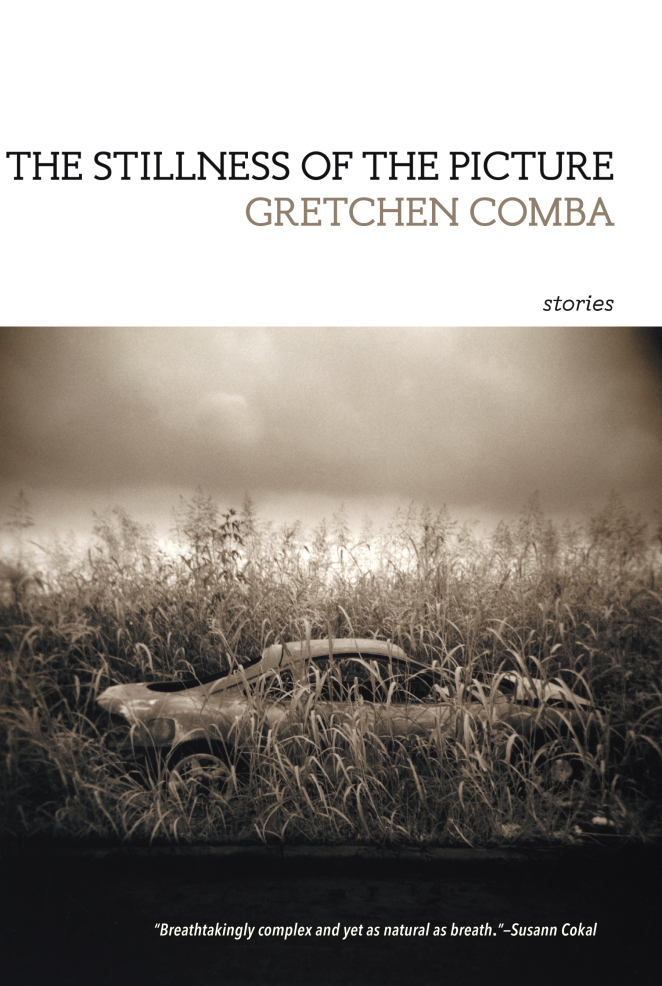

Gretchen Comba just published her first book, The Stillness of the Picture, to enthusiastic reviews. Her short fiction and scholarly work has appeared in a number of journals, including Alaska Quarterly Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The North American Review, MidAmerica, and Resources for American Literary Study. She is a recipient of the F. Scott Fitzgerald Award for Short Fiction and the Yemassee Award for Exceptional Contribution to the Magazine.

Comba may be primarily a writer of fiction, but she has taught workshops in all genres and contributed scholarly research and nonfiction to anthologies. Naturally we wanted to know about her juggling act and how she manages to flourish in so many disciplines—and how she teaches her students to juggle their words too, so that each piece they write achieves what she calls “the feeling that is like no other.”

BROAD STREET: How do you define “truth”—in nonfiction, sure, but also in other genres? For example, how do you see the stories in your new collection as telling the truth in some way?

COMBA: That’s a good question, one that I am not certain I can answer directly. Let me try to frame it around the idea of what I think truth in fiction is. In that context, I would say that “truth” is achieved in the marriage of the literal and metaphorical. It is a meaning or an essence (God, the phrasing sounds so grand, and I do not mean it to, for I am only talking about theme, which I suppose is just one person’s conception of the world which may or may not be anyone else’s conception) that emanates from a story when what a character literally wants matches up with what she metaphorically wants. For example, in my story “The History of Florida,” the main character literally wants to move to Florida with the man whom she loves; metaphorically, she wants ideal love. I would say that the “truth” of that story is wrapped up in the idea that ideal love does not exist, and that each of us, no matter how depressing the thought, lives alone with her constructed ideals that cannot be realized. And of course I didn’t know this “truth” until I finished the story. I hope this answer isn’t too much of a cop-out.

How do you determine something simply has to be written about?

Like many writers, I subscribe to the theory that the story chooses the writer rather than the other way around. That said, by the time I finish a story, it usually bears little resemblance to the story I started out to write. So I guess that I never really determine whether or not something is worth writing about, although perhaps I should. Instead, I just let the story go where it wants to go without determining what it should or shouldn’t be, or deciding whether or not the subject matter is worthy of being written about.

At first, I am typically driven by intuition, and then I find that I am being led along by the rhythm of the prose. I rarely allow intellect to drive a story (and when I do, which is when I am frustrated to the point of despair, I always regret it); instead, I wait until the “real” (hmm, do I mean “true”?!) story shows itself, and then I let the intellect kick in.

At that point, I have to decide whether or not the scenes are moving the story forward, whether or not the dialogue bears metaphoric weight, whether or not the motivation is adequately expressed. This last stage, though, is relatively easy and fun; the work that I do to get there is what can be demoralizing.

Your writing is very full of sensory description—readers can really see the world through which your characters move, and feel and smell it too. How do you select the details that will connect with readers?

Thank you for your generous comment. I hope to answer your question just as generously. When I sit down to write, I have one goal: get in. What I mean by “get in” is, I think, what Gardner means when he writes of “the vivid and continuous dream” of fiction [from The Art of Fiction]. In other words, I try to lose myself in the story, to be inside it, rather than worrying about plot, character, or any of the other basic elements of fiction.

When I “get in,” I am seeing, hearing, and smelling the world along with the characters. I usually achieve this state (when I do achieve it, which is far less often that I would like), by doing one of two things. First, I do it by ignoring my own story (despite the fact that the document is open on the computer in front of me) and instead reading a different piece written in the style or concerned with the subject matter that I am interested in at the moment. As I read, I wait for something in the text to spark a memory in me, a memory that leads me back to my own story (the damn cursor still flashing). I type out that memory, all the time trying to keep with me the sensations that I experienced when I first hit on the memory while reading.

Second, I re-type the story, or part of the story, on which I am working. Something about the process of re-typing gets me into the rhythm of the story, which in turn gets me into the heads of the characters, which in turn allows me to experience sensory details along with the characters. In terms of selecting the details, I don’t do this until very late in the game. Once the characters start talking and walking on their own, I begin to consider which images carry metaphoric weight and which images contribute in other ways to the story. At that point, I make decisions about which details to keep and which ones to cut.

How do you create the voices in which you tell a story or explain an idea? Is there some process, once you’ve written them, by which you evaluate the honesty of the piece?

To be honest, I rarely, if ever, discover a character’s voice until I am in the last stages of writing a story. Only after I have written a story in countless ways, with countless failed plots, scenes, and summaries, do the characters begin to talk in their own voices, not to mention walk around and do things on their own. The one exception to this case, if it is indeed an exception, is “The Stillness of the Picture.” This story took an incredibly long time to write (actually, all of my stories take a long time to write—I am very slow) and was at one point upwards of seventy pages long. (I am embarrassed to admit that last particular truth, lest another, more brilliant writer think me a fool for writing so much for what turned out to be such a very short story.)

In any case, my father was the son of Italian immigrants who worked in Pennsylvania coal mines in the early part of the twentieth century, so I had some knowledge about coal mining in that place and time. And yet, I couldn’t transmit that knowledge (hearsay, really) into the mouth of a character who had anything to say, much less a distinct voice with which to say it. I was reading a lot about coal mining at the time, and in one book I came across a brief interview with a miner. In ten sentences (yes, I counted), and in the voice that became the narrator’s voice in “Stillness,” this miner told the story of a woman named Sophie Dabio, who became Josie Daglio in “Stillness.” After reading the miner’s words many times, I told myself, “Okay, Gretchen. All you have to do is put each of the ten lines at the top of ten different blank Word documents, and then, riffing off each single line, write a full single-spaced page.”

I did this, and the magic happened. Of course, though, I couldn’t have done this without having written the original seventy something pages that filled in, albeit in a very different way, those ten blank pages. In terms of evaluating the honesty of a piece, I usually can’t do so until I am away from it for a while. After I finish a piece, or at least think I have finished it, I set it aside for a long time. When I return to it, I read it with a cold eye—I am outside the story now—that allows me to judge whether or not I have hit upon that elusive truth endemic to all good fiction.

When you were starting out as a new writer, what gave you inspiration and kept you going?

Wow. That question is both a hard one and an easy one to answer. In short, I was given inspiration and the impetus to keep going by other writers’ short stories. I distinctly remember reading Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” when I was a sophomore in college. I was entranced. I was so entranced, in fact, that when my parents and younger brother came to visit me in Tallahassee, I refused to go to dinner until they listened to me read the story aloud to them. I still remember my poor brother, sitting in the chair in the motel room, continually interrupting my reading of the story to say, “Is it almost over?” and “Can we go yet?” and “I’m starving.” Once I finished reading the story, we went out to a Steak & Ale, where I did nothing but talk about the O’Connor story. Clearly, I was a bit obsessed, not to mention self-involved. But back to the original question: I am not completely sure that what sustains any writer, new or old, is anything more than the stories of others—stories that, because of the language, the structure, the characters, the perspective, the setting, the marriage of the literal and the metaphorical, move one to emulation.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers–in any form–and where did you learn that tip?

I hate to be unoriginal here, but I can only offer this clichéd bit of advice: read and write. A lot.

Advice aside, however, I would like to say something else to aspiring writers, which is this: No matter how awful you feel about your story, keep going, even if you do so by writing another story—for that “new” story, in my experience, is always linked to the one that was set aside. I can’t begin to count the number of times I have looked at a story on which I am working and been dismayed (anguished would be a more apt word) by the fact that I seem to be getting nowhere, that no matter what I do, the story just will not become a story that has what William Maxwell called “the breath of life.”

At these moments I am lonely, bored, fearful, anxious, and, worst of all, hopeless. I am in despair. Honestly, I don’t know why I keep going (and sometimes I don’t—but those are the worst of times, and I always regret them). Yet most of the time I do go on. I tell myself that the creation of fiction, of any art really, is a matter of constant perseverance amidst continuous defeat and ever-present doubt.

And so I say again, in the hope that my doing so will make the process a little less disheartening for beginning writers: Keep going, for if you keep going, the “real” or “true” story will reveal itself. And when that moment happens, the feeling is like no other.

True stories, honestly.

Author photo by Bree Davis.