“I didn’t intend to write a memoir. I was on a personal search for my biological mother, which I hadn’t intended to do either. You know what it’s like, the big things in life you never plan: you micromanage everything, and then the big things come along, and you never saw them, you never expected them. And that’s how it is.”

In February 2013, Broad Street had the rare opportunity to interview Jeanette Winterson, revered author of multiple novels, including the widely popular Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. She had just published a memoir, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?–and her biography is far from normal. The adopted daughter of Pentecostal parents in Accrington, England, Winterson grew up with a love for books and reading. After leaving home at sixteen, she went on to attend Oxford University, where she wrote her first novel at age twenty-three.

In February 2013, Broad Street had the rare opportunity to interview Jeanette Winterson, revered author of multiple novels, including the widely popular Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. She had just published a memoir, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?–and her biography is far from normal. The adopted daughter of Pentecostal parents in Accrington, England, Winterson grew up with a love for books and reading. After leaving home at sixteen, she went on to attend Oxford University, where she wrote her first novel at age twenty-three.

Chad Luibl sat down with Ms. Winterson after her presentation at the AWP Conference in Boston, and they covered everything from the writing of her memoir to her love for her cats, and the changes she has undergone as a writer throughout the years. The full interview is in the sold-out debut issue of Broad Street, but we present it here, specially formatted for online reading. You don’t want to miss it!

Sample some of the conversation here, then read the full interview: “It’s Always Some Battle.”

BROAD STREET: Was the writing process different with a semiautobiographical novel, such as Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, as opposed to an entirely autobiographical memoir?

WINTERS: No. I’ve never separated out the me that I am in the books that I write. I almost always write in the first person. It pleases me to do that. Everything that we write passes through us — there’s nowhere else for it to pass. So it doesn’t matter whether you are writing about yourself in the eighteenth century, as I did in The Passion, or whether you’re setting yourself on another planet far in the future, as I did in The Stone Gods, or whether you’re writing something so absolutely close to your own life.

You know, there is a fatuous comment that is always peddled in creative writing courses about “writing what you know,” but what you know is whatever is connected to you in some way, and that might not make any objective sense. You know, if you have a connection with your material, whatever it is, then you are writing what you know. And it’s passing through you. That’s why I don’t make those distinctions. I’m interested that now, as the novel is beginning to falter as a form, all we’re seeing really is this wish for people to accept that they’re at the heart of their own narratives. However you disguise [narrative] it is always a series of confirmations or disguises — but it’s you. I mean, you are the writer.

* * *

If you’re a good writer, you should be able to write anything. I think of this as a workshop: If you come along to me and say you want a chair, or a table or a cabinet, I should be able to do that. It’s all a different shape, but I’m working from the same material. And so what I mean to say is there is a certain level of professionalism and skill whereby, you know, if The New York Times rings me up today and says they want a piece by five o’clock they can have it and it will be at the right level. So that’s the bit that you write. As a skill, expertise, all those things. But when you’re doing creative work in that deep-dived way, then you’re doing something that is accessing all the other parts of the self, which are not generally needed, say for even high-level journalism or quite a lot of nonfiction. You need to use your brain and your experience your ideas, but you’re not going to into those other strange places where you don’t know what’s there any more than anybody else does. And that’s where the dangers start, because you’re always going to uncover things that will challenge you so that they can then challenge other people.

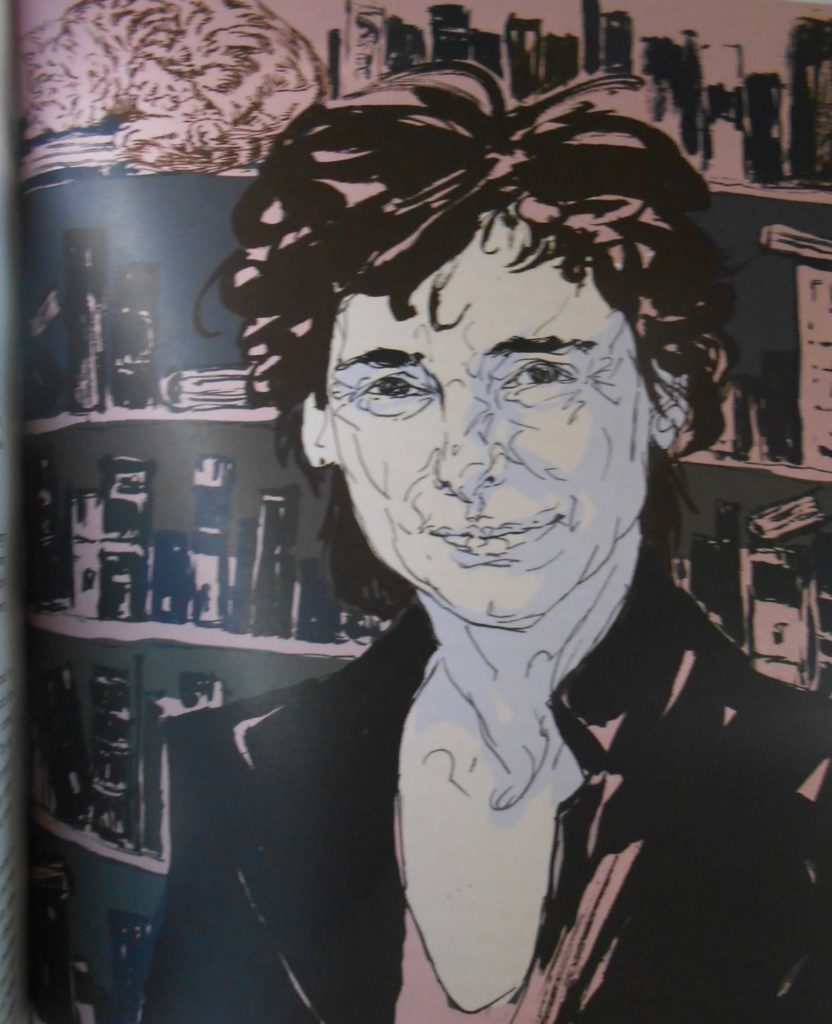

Portrait of Winterson by Shawn Yu.