Online Exclusive: “Red Ferry, Blue Ferry,” by Michael Fallon.

by broadstreetmag on Feb 2, 2018 • 10:47 pm No CommentsIn which the author triangulates Ireland before Google, cell phones, and GPS.

“I thought myself pretty clever to have come up with what seemed a foolproof method … The islanders knew that their Ireland and mine were not the same place.”

(This feature is also available, in slightly different format, on Medium.)

“Red Ferry, Blue Ferry”

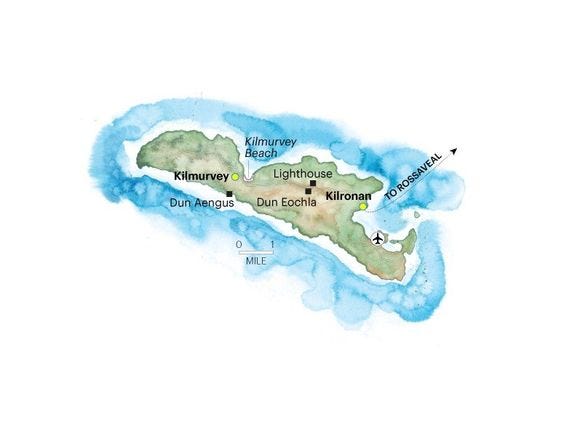

It was the last full day of a week I’d spent in the Aran Islands, and I had been trying to get a ferry from Inishmore to the big island, as they called it, back to the city of Galway. Everyone I asked said it couldn’t be done. I kept saying over and over that I had come here to Kilronan, the main harbor of Inishmore, on a ferry from Galway city — so why couldn’t I take a ferry right back to it?

The ferry doesn’t go there, I heard from every Irish person I met, islander and tourist alike.

So where did the ferry come from that brought me here from Galway? I would ask, incredulous. How did the ferry get to Galway in the first place, before it came here?

There’s no ferry that goes to Galway city, was the flat reply.

To an American traveling in 1986, Ireland was an eccentric place. First of all, the Irish assumed you were a decent, well-meaning person until you proved otherwise, and they had — and still have — a great love for stories and the talk. Yet strangely, unless you asked precisely the right questions, that love of elaboration seemed to disappear if you wanted all the precise and pertinent information about where you were going and how you were going to get there.

Anyway, this was how it was when I, an Irish-American from Baltimore, went to the Aran Islands in June 1986.

It was just a month and a half after the bombing of TWA Flight 840 from Los Angeles over Argos, Greece, and the details of the bombing were horrific. A young Lebanese woman had placed a bomb under a seat during an earlier flight, and on its way to Athens, the bomb blew a four-by-three-foot hole in the fuselage. Four passengers, including a mother and her nine-month-old baby, were sucked out of the cabin. Not surprisingly, at the time I was set to travel, many Americans were afraid to take a flight to Europe.

It was also long before the internet, cell phones, and Googling, so in a sense I was on my own and left to my own devices to find my way.

Sure, I had a general mental picture of the map of Ireland in my head and knew where the major towns and cities were — and yes, I had paper maps, but those don’t always have the best local pubs or the most interesting ruins marked, and often I had to ask for help with the when, where, and how of buses, ferries, and pathways.

As for the talk: Though I really enjoyed the friendly and often interesting twists and turns of these conversations, I would also find myself tapping my foot. I was impatient, for instance, to get out of an Irish version of a 7-Eleven and back on the road. After all, I had other places to go and people to meet before sundown and the first pint of the evening. I laughed and learned, and was thoroughly entertained; yet when I got back to my journey, there was often something unexpected out ahead of me as if hidden in mist, something not covered in all the talk.

“The long, lyrical echo of Irish travail had filled me with a longing to know the country of my ancestors and to feel some sense of belonging there.”

If I kept my mouth shut, I was sometimes mistaken for an Irishman, if not for an islander. As soon as I spoke, my American accent gave it all away, yet I was still met with kindness, warmth, and friendliness, which was entirely natural for Irish people, who for some reason hadn’t yet had it all hammered out of them: Fallon, now that’s an Irish name, isn’t it?

Sometimes I was treated like a distant cousin — maybe because there was still an echo of the Gael in me — but often I was referred to as The American and then was again aware of all that made me separate: the ocean, the divergent histories, and the years.

I never felt more like The American than when I was asking for directions.

***

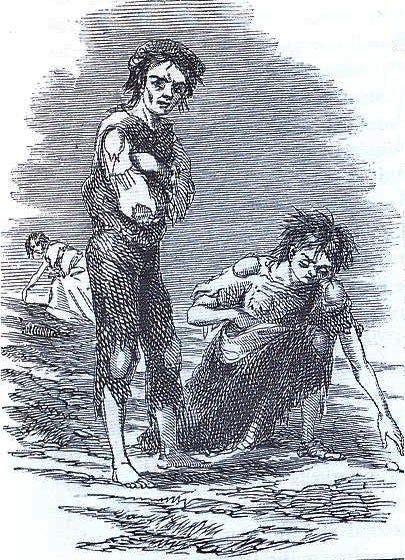

The Aran Islands are one of the few areas left where people grow up speaking Gaelic as a first language. Called Oileain Arann in Irish, these islands are in the extreme west of the country, long considered the most traditionally Celtic and the least affected by the long centuries of English rule. They are thus not only one of Ireland’s most remote places but also, according to the English, among its most uncivilized and, therefore, wildest, places.

You may have heard of John Millington Synge (1871–1909). He was an Irish Protestant but a non-native islander as well as a non-native Gaelic speaker, so he’s considered a foreigner here. He lived briefly in the islands and based a play, Playboy of the Western World, on Irish types he had supposedly observed on the Aran Islands and elsewhere in the western counties. In the play, Christy Mahon, the main character, becomes a hero in the local tavern and then the town (especially to the women) by enthralling everyone with the story of how he has supposedly murdered his father, a task he unfortunately must attempt twice to make his story true. Still, success somehow eludes him as his father, though twice presumed dead, miraculously manages to survive both attempts.

When it debuted in 1907, the play was famously booed off the stage and caused a full-scale riot at the Abbey Theatre of Dublin, which boiled over into the streets. The Dubliners hated Synge’s portrayal of backward, superstitious, drunken, and dangerous peasants from the Wild West of Ireland. Nonetheless, either in spite of or because of Synge, some Irish tourists told me that the Aran Islands were considered the heart of the heart of the country.

I never worked up the nerve to ask any of the islanders what they thought of the play. Anyway, I resolved to make sure never to claim I was the Playboy of the Western World, as some ignorant American might do.

***

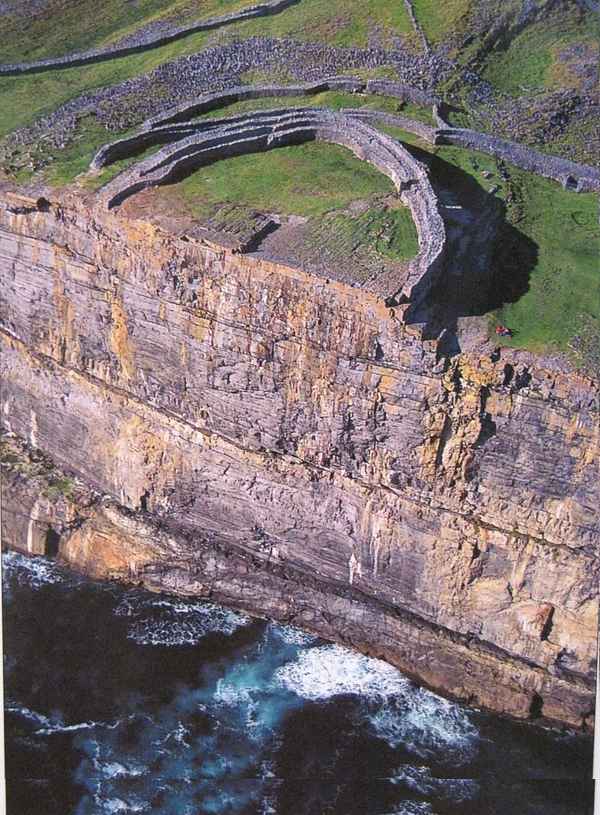

The two Iron Age ring forts I visited on the island of Inishmore — known as Inis Mór to the Irish — are still strongholds in my memory: Dún Aonghasa, the big fort (its name Anglicized to Dun Aengus), and a smaller one called Dún Dúbhchathair, or the Black Fort. They are a relatively short uphill walk from Kilronan, with signs marking the way. (In my day, the signs were black-and-white; now they’re mostly red-and-white.) Both forts were built without mortar, by fitting stone to stone and so building a sturdy, solid wall without a crack you could fit the tip of a finger into.

I called them ring forts, but each of them is half a ring, or several halves. They were built at the very edge of steep cliffs three hundred feet high, with the churning sea below. No need to complete the circle and build a wall on the Atlantic side; if your enemies managed to reach the keep and storm the walls, the only option was a leap of faith off the cliff, into the wide sky, the rocks, and the waves.

Dún Aonghasa is a formidably beautiful feat of engineering and construction. But what I saw when I looked down from the rampart into the wind was fear. Terrible fear was what built these walls — large enough to hold every man, woman, and child who could get there in time, and whatever livestock they could manage to bring with them. Fear of that unfamiliar sail on the blue plain of ocean — Celtic tribes from the mainland, or Vikings come to steal gold and cattle, to murder and enslave.

I had to cross the spine of the island to get to the smaller Black Fort. Here the rock was pitted and puddled with rainwater and had deep fissures and cracks in it. If I wasn’t careful where I stepped, I could easily get a foot caught or break a leg. And if that happened, I could have lain injured a very long time, for there was no one within sight and not a sound from man, beast, or engine.

There was no gate into this fort, either, no opening in the twenty-foot walls but a single two-and-a-half-foot stone between the end of the wall and the empty air: a three-hundred-foot drop into rock-studded foam. I gingerly stepped onto the flat white slab —

And Good Jesus! As if to justify my fear , two gray dogs shot suddenly past on either side of me. I tottered for a breathless moment, then stumbled into the fort … and lay there for a very long while in the thick mat of grass, catching my breath and listening to the systole and diastole of the sea.

Though it is true I had an easy time following the signs and finding the huge and obvious Dún Aonghasa and the less obvious Black Fort, it might have been nice to have a sign that said, DANGEROUS ENTRANCE, WATCH YOUR FOOTING! orBEWARE OF GRAY DOGS! To the Irish, this sort of information is extraneous. They will cheerfully point you in the right direction, but you had better watch your step.

***

It was on the road to Clifden, in the region of Connemara, near Galway, that I saw the man sitting on the wall.

The wall was out in the middle of nowhere, in a broad, stony, treeless valley, not a house or other type of building anywhere reasonably close in this open country where I could see for miles in every direction. I had stopped to take some pictures of the three bens (bald, rocky mountains) and the faroff panorama of a monastery by a lake, when I saw him nearby.

He sat with his feet dangling, perfectly still. He acknowledged my presence with a minimal nod of the head — and then he went on sitting on his wall, motionless in the middle of noplace.

He just sat and sat and sat and didn’t move — an oldish kind of man in the typical Irish tweed cap, holding a cane or a walking stick. For all I know, he had been there an eon before I came and he is still out there. I doubt if he even got up to take a leak.

The western Ireland I found in the late eighties was one in which men sat on walls until they wore out the stones.Time and place and the laws of physics were different in that Ireland.

So you’ve missed the bus? Oh well, there will always be another. So let’s go next door to the pub for the crack of the evening (the high point or best part, especially of music or conversation)— let’s have a whisky and I’ll tell you about the Norman castle and then we’ll go have a look at it.

In that Ireland you were never late or lost. There were no such conditions; it was as if time had stopped.

***

I found out early on that if you had the American fixation on getting precise and useful information quickly and easily, in Ireland, you were basically out of luck. Important details were often left out of conversation, I suppose because no one thought to tell me what I did not think to ask, or I did not phrase the question exactly.

This was a source of considerable worry.

I decided I would conduct my own statistical survey whenever I had to get walking or driving directions or catch a bus, train, or boat. I would ask at least five different people every question I could think of from every possible tack, weigh their replies, compare the answers, and sort out what was consistent to try to figure out what must — at last — be so.

I thought myself pretty clever to have come up with what seemed a foolproof method. I conceived of it as a kind of triangulation. I stood at the first angle and the Irish stood at the second, while the answer was at the third. If I could but get the second angle right, I would surely know the truth.

On my last day in the Arans, as I arranged to go home, I found that there were two ferries leaving Kilronan (Cill Rónáin) harbor, on Inishmore, for on the mainland. The red ferry cost ten pounds and the blue ferry thirteen. So I asked at the ticket window what the difference was.

No difference, I was told. They both go to the same place.

Even after asking every conceivable question and getting the same answer, I felt extremely uneasy. I could find no American, Brit, or German among the crowds who might run by a more precise system of time and navigation. So I wandered the streets of Kilronan, asking old men, young women, tourists, islanders, and Irish people of all shapes and sizes:

What is the difference between the two ferries?

No difference.

But why then does the blue ferry cost more than the red ferry? Do they both go to the same place?

Same place, I was told. No difference.

I hardly dared to tackle another part of the problem that also made no sense: I naturally assumed that since I’d taken a ferry (what color it was, I didn’t remember) from Galway city to Kilronan, I could take the same ferry back to Galway harbor. But both the red and the blue ferries inexplicably went to Rossaveal, an obscure town on the Galway coast. How was I supposed to get to Galway city and then to Shannon Airport for my homebound flight?

Isn’t there a ferry that goes to Galway city?

No ferry goes there, I was told.

So then I would plead, But I took a ferry from Galway to get to Inishmore. How did that ferry get back to Galway?

No ferry goes to Galway.

But when the ferries leave the mainland, where do they go? Do they go to Galway city? How do they get back here? How did the ferry I took from Galway get there in the first place?

I took to demonstrating my quandary by drawing triangles in the air and showing that the ferry had to somehow get back to Galway city from Inishmore to be in Galway in the first place, but it was no use. I got not only the same answers but a bit of thetalk as well.

No difference. Same place … My uncle lives in Chicago. His name is Michael Feeney. Do you know him? … There is no ferry that goes to the city of Galway.

What else could I do but buy a ticket for the cheaper red ferry?

***

I grew up among generations of Irish Americans, who because of — in spite of — past persecution, clung to their ethnicity and, yes, while it’s very apparent to the native Irish that we are Americans, we still have retained a lot of the Irish attitudes, behavior, and general way of being. The Irish love America. It is a source of great pride for them, as Irish emigrants have had so much success here in the United States, including Presidents Kennedy and Reagan and an endless steam of important politicians and public figures. Though the Irish are indeed very tribal, they often treat us like cousins, if not like immediate family. So I got along very well with the Irish, and I could read them pretty well most of the time.

This is why I still cannot understand how I could not seem to get — what seemed to me — obvious, important travel information out of them.

On my last night I had dinner with a Brit named Peter, who was staying at my B & B, up the hill from Kilronan proper. He was tall and thin and neatly dressed — informally, but like a business type on vacation, with glasses and short curly blond hair that had a slight reddish tint to it. A friendly-enough guy, a little stiff, I think as much because he was a stockbroker as because he was a Brit from London.

And I suppose I was the overly friendly, loquacious American. But I was Irish American and so, I thought — despite my communication and navigation struggles — a bit more tuned in to the Irish and able to read them better than he could.

I had told him about this restaurant in Kilronan, where I had eaten several days before. Though the place was inexpensive, it still had white tablecloths and served wine. I recommended that we order baskets of corned beef sandwiches, which were easy on the wallet. The corned beef might have come out of a can, but it tasted good, and each charming basket held about eight small sandwiches, the amount right for one hungry man.

While we waited for our meals, Peter, being thoroughly and obviously English, told me how amazed he was that the Irish were so polite to him and that they had basically treated him well. He added, In spite of all the terrible things we did to them.

When the meal was served, however, we noted that while I had gotten eight sandwiches, Peter got only five. Peter’s face flushed with annoyance and he called loudly to the entire staff of the restaurant, How is that I have only five sandwiches while my colleague here has eight? How many sandwiches come in a basket? I can only call his manner imperious. It definitely had the air of command about it — a master-to-servant tone.

All the waiters and waitresses looked like college kids from the Irish mainland working summer jobs, with rolled-up sleeves and green aprons. They stopped what they were doing and visibly stiffened as they regarded him.

There were not many customers at the time, but the silence went on long enough for me to want to duck behind my water glass with embarrassment. Here I was, a traitorous Irish-American, sitting and having a collaborative meal with a most imperious Brit.

Our waiter replied, It says “a basket of sandwiches” on the menu but it doesn’t say how many.

It was hard to tell if the waiter’s face was flushed, too, or if he naturally had a reddish face. But his delivery was curt and he immediately turned his back, putting fresh silverware on a table.

“I think now that we were in two different countries…. Each of us was no doubt looking for a different Aran.”

The restaurant filled to the brim with annoyed silence. No more sandwiches came out of the kitchen.

Peter did not push it further and said nothing more; he now seemed completely unruffled by the response to his complaint. I think he realized that he wasn’t going to get anywhere and so let the matter drop very quickly. Maybe this was just British cool — a kind of stiff upper lip. But I wonder if he saw what I saw. I didn’t even think of offering him a sandwich. I was too busy being shocked, embarrassed, and annoyed.

I think now that we were in two different countries.

***

Another place I frequented during my week on Inishman was Jimmy Mack’s pub. One afternoon, after my tourist rounds, I met a local schoolmaster and we had a few pints together at the pub. He was an Irishman from the mainland, and he was fully fluent in Gaelic, with a wide knowledge of Gaelic literature. But because he did not grow up speaking Gaelic as a first language, he told me, the islanders said he spoke book Irish. So the people of Aran considered him a kind of second-rate Irishman and a foreigner.

Then what was I, I wondered, being three generations removed from Ireland? A fourth-rate Irishman? No, not even that, an Irish-American with a strong but foolish desire to find the Ireland in himself and himself in Ireland, who mispronounced a few phrases of Gaelic and romanticized the lost language, the bitter famine, the music, the people, and even the stones … The islanders knew that their Ireland and mine were not the same place.

I wondered then, and I wonder now: What are we looking for when we travel?

I think it varies with the traveler and the reasons for traveling. It is no coincidence that the words travel and travail have the same root and once meant the same thing. The Irish emigration to the United States in the 1840s was travail, not travel. And the long, lyrical echo of that travail — in the songs, the poems, the stories, the plays, and the novels; in the terrible history and the last slow unraveling of the once clannish, close-knit Irish community in my native Baltimore —had filled me with a longing to know the country of my ancestors and to feel some sense of belonging there.

I am sure that the reasons we have for leaving home and what we are looking for — whether safety, adventure, drama, or belonging — have everything to do with what we find, whether it’s illusion or disillusion, another harsh reality, or the land of our dreams.

I think Synge found the country he wanted, but it was not the one in which the Irish at the Abbey Theatre hoped to recognize themselves. It was the one that had had so often been used to wound them: part caricature and part truth.

The schoolmaster, Peter, and I had all brought our unavoidable histories and preconceptions with us to this place, which had its own impenetrable history and prejudices. Each of us was no doubt looking for a different Aran. The schoolmaster, who might have thought he would be accepted “in the heart of Ireland” thanks to his fluent, educated Gaelic, was not considered part of the tribe of Aran because he was from the mainland and his Gaelic was formal. Peter, because of his English accent and bearing, would never quite get past the long ingrained catastrophes and resentments. After the initial Irish politeness, there would often be a dropped smile, a wary stiffening in the face.

After my dinner with Peter, I found my way to Jimmy Mack’s for the crack of Saturday night. The band was so blasted they played with eyes closed in a transcendental state of drunken intensity, the fiddlers and strummers like Buddhas in whisky nirvana. The place rocked back and forth to the clapping of hands and the stamping of feet, as if the waves were playing keep-away and the bar were a tugboat tossed in a storm.

And after the pub closed, there was a traditional cèilidh, or ceili,a dance party, in what looked to be a church hall located up the long, steep hill from the harbor. There a large group of musicians had gathered to play waltzes, jigs, and reels. I danced with a young American woman, the only other American I had met on the island.

The days of high June are the longest of the year, and this far north the twilight lingered. The sky was a glowing indigo well past midnight. In this, the real Celtic twilight, the crowd streamed onto the main street of Kilronan.

To go home, most people went either up or down the hill. There wasn’t much to the town on the right or left, only the one long, steep main road that went the length of the island. In the intense blue glow, only the shapes of our bodies could be seen in silhouette. We were rounded-out forms in blackened bronze, the outlines of a head and the slope of the shoulders — not a face could be recognized.

The young islanders laughed and talked quietly in Gaelic. I thought they had no idea I was not one of them — a shadow among a crowd of shadows — as gate by gate, house by house, they kissed, said good-bye, and turned off.

The crowd gradually thinned. In the darkness, I belonged. It seemed to me that I approached the crown of the hill among my living ancestors.

As I came to the gate of my B&B, the voices moved on up the road ahead of me and merged into the distant lull of waves. I no longer felt sure what century it was or how to pronounce my own name.

***

It was with overwhelming nausea and a sick sense of irony that I boarded the red ferry the next morning. I had a severe case of food poisoning. I wondered if the Englishman, Peter, were suffering the same plague and if the provinces of his stomach and bowels had now revolted against him. Anyway, he was, at least, three sandwiches better off than I was. Every pitch and roll of the red ferry was recorded by a queasy seismograph in the sloshing pit of my stomach.

A dozen people or so sat on the benches as the ferry chuffed along: middle-aged couples, some with children — mostly they looked to be tourists. They probably thought I was seasick and so left me alone. I sat on a little white bench by myself, silent and standoffish, afraid to open my mouth.

Off the bow and not far away, the blue ferry also plunged and tossed toward the mainland.

We arrived at a dock at nearly the same time. The red-ferry people walked up the pier and into a parking lot, where they got in their cars, slammed the doors, and drove away. The lot emptied fast.

The blue-ferry people, meanwhile, walked to a turnaround where a bus waited, doors open for them to board. A sign above the windshield spelled out GALWAY in big white letters.

I was struck in a flash by a sudden insight, as if a flaming meteor had dropped out of space and plocked me on the noggin. What a grand, splendiferous fool I was!

Everyone on the blue ferry had a bus ticket to Galway — that was why it cost the extra three pounds!

I stood there alone without a ticket and looked around in a panic. There are some profoundly empty places in Ireland, and this was one of them. Nothing here but the Atlantic Ocean, a pier, a parking lot, a turnaround with one white house on it — and, of course, the bus, which was idling before takeoff but definitely not waiting for me. The seats were plainly reserved for passengers of the blue ferry.

I still felt sick as a marmot but I had to do something. I couldn’t approach the bus without a ticket, and there was no way now of getting one.

I still had that American sense that giving cash directly to a bus driver is like offering an illegal bribe. I felt it could easily provoke anger and make the driver look dishonest in front of a busload of witnesses. I assumed he would not take the money, and any attempt to persuade him to let me on the bus could get me in trouble. I hadn’t thought to make friends with a fellow-passenger who might have helped me. I was just plain stuck the middle of noplace.

But then I noticed a tall, gaunt, dark-haired man who I somehow knew had not come from either ferry, walking up the turnaround toward me. With completely naked desperation and absolutely no context, I announced to the stranger, I took the red ferry by mistake. I need to get to Galway. What can I do?

He pointed to the white house.Go knock on the door and ask the woman who lives there.

This sounded absolutely crazy to me. But it seemed the only option I had. I was too desperate to ask the gaunt man who the unknown lady was and how she could help. I was all out of triangular questions and had to take it on faith — I walked up on to the porch and knocked.

A woman in a blue knit sweater came to the door. I stumbled all over myself as I explained about the bus and the two ferries.

What can I do? How can I get to Galway? I said finally.

You can try offering the driver some money, she said.

I had to trust that she was right, that paying the driver on the spot would be not a criminal act but a matter of convenience in an easygoing country. I thanked her, turned, and ran toward the bus with my suitcase in one hand, digging with the other for a fistful of Irish pounds.

And I still don’t know how the ferries ever get to the city of Galway.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

— — — —

Like what you’ve read here? Then please follow Broad Street on Facebook and our website.