“That’s part of researching’s charm—I live as a time traveler …”

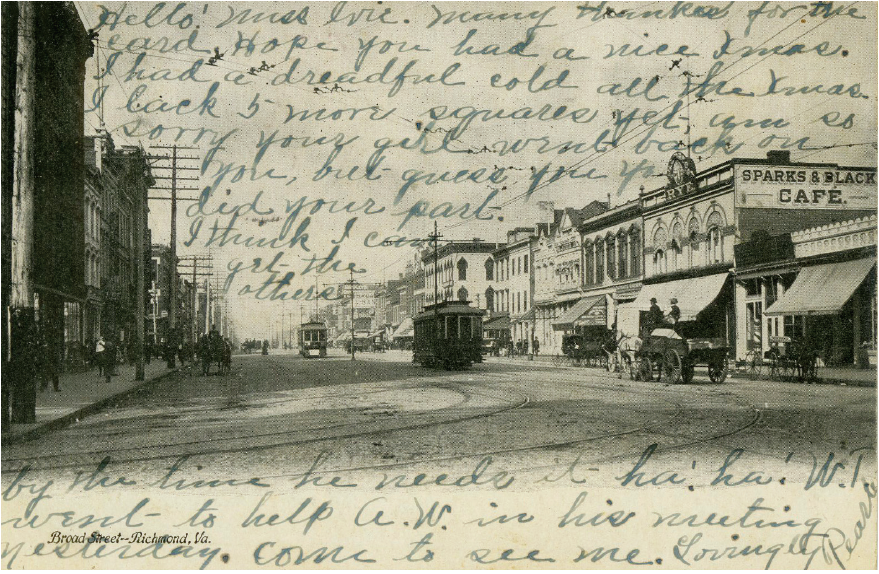

Above: used postcard, c. 1911, showing part of Richmond’s Broad Street.

*

Editors’ note: When we started to plan the “Maps & Legends” issue, we got curious about the legends that might adhere to the building in which this magazine and a variety of student-run media are housed. 817 Broad Street in Richmond, Virginia, has gone from salad days through urban decay, to emerge again in a heyday as the university gave new life to some buildings and tore others down. Broad Street tells the story of the colonies and of the South; its pavement and trolley tracks long divided white from “colored,” and the changes to number 817 recap the history of town and university.

We had to map the story. So we contacted local historian, magazine columnist, and writer Harry Kollatz, Jr.—himself something of a legendary, behatted figure in Richmond—to dig up the rubble.

This is our story. And it’s the story of Broad Streets all over the world.

Addendum, 2019: Our office is no longer located at VCU or on West Broad–but we will forever occupy a Broad Street of the mind.

***

Here at 817 West Broad

The storied past of our magazine’s office is the history of Broad Streets around the nation.

From our “Maps & Legends” issue, winter 2017.

Harry Kollatz, Jr.

When spelunking through the city directories that form the structure of my research into buildings, I rarely brush across names recognizable from my own life. That’s part of researching’s charm—I live as a time traveler. Sometimes what’s most compelling is the shape of the new names in type on yellowing pages and how they sound when whispered aloud in the library. They’re an incantation.

We begin with the facts:

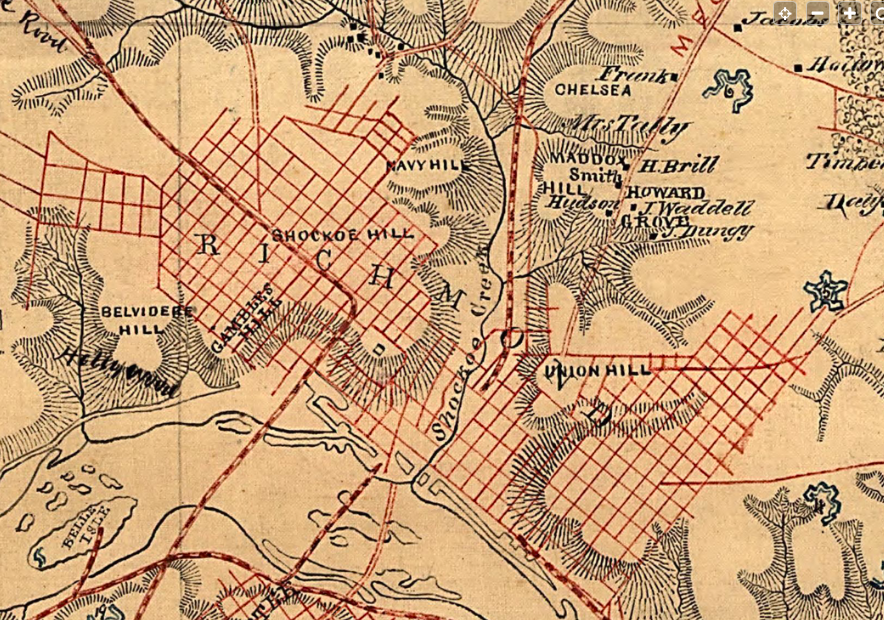

Sometime in the nebulous colonial past, Broad Street started as a regular-sized dirt thoroughfare on Richmond’s northern edge. It intersected with the major north-south roads and was known variously as the Richmond Turnpike and the Deep Run Turnpike. In 1782, Governor Thomas Jefferson lengthened the street and designated it “H.” It’s not named “Broad” on city maps until 1845; the change seems connected to the arrival of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad in 1834.

Broad Street’s First Baptist Church–later renamed First African Baptist Church–was founded in 1842 at the intersection of Broad and College. Its first congregation was largely slaves; the deacons and first minister (who was actually a slaveowner) found loopholes in the laws against teaching slaves to read and write. After the Civil War, the church became an important center for freemen. The original church building was demolished; a later building is now part of the Medical College of Virginia campus; the congregation moved in 1955. This picture, taken in 1865, documents some of the first free congregants.

The RF & P’s trains ran down the middle of Broad from a station at Eighth and H and tracked west until veering north at Hancock Street. In the bustling city, the line became a frequent challenge for pedestrians, horses, and other conveyances. Injuries, a September 1873 death, and consistent petitioning by residents persuaded the dithering Common Council to remove locomotives from Broad. In 1875, accordingly, the RF & P established the Elba Station, taking its name from a then-remote mansion named in waggish tribute to Napoleon’s exile, at Belvidere and Broad. This is, incidentally, the site for VCU’s brand-new Institute of Contemporary Art—a mere block or so from Broad Street’s offices.

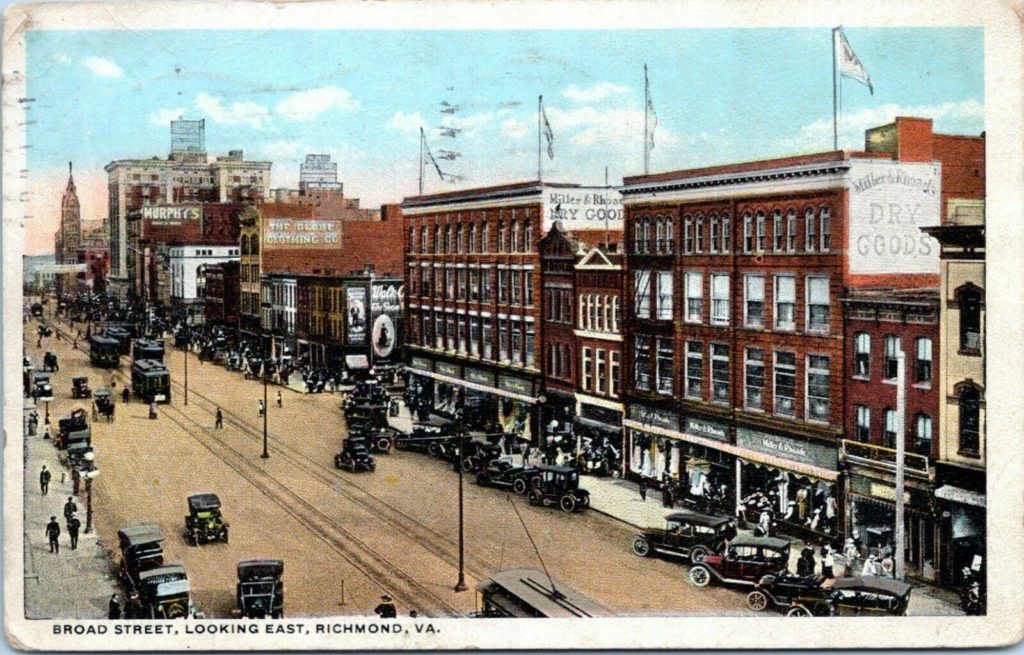

The newer, tidier Broad became the site of the world’s first unified citywide electric streetcar system, which ran after 1888. The trolley made the street the center of Richmond’s mass transit and supported the foundation and growth of commercial enterprises on both sides of the street. The “both sides” element is crucial, as the trolley tracks effectively became a color line downtown: On the south side of Broad were located large department stores and fine shops for white customers, while the north side housed businesses catering to the substantial African American population who lived in wards and neighborhoods behind. On that side, too, sprouted many motion picture houses and saloons—perhaps another reason mothers admonished their children against crossing over the tracks and into temptation.

On the north side of the street, across from our building and in a cityscape completely different from what we see now, number 814 became the home of the Richmond & Chesapeake Bay Railway Station in 1907, designed in an elegant Italian Renaissance/Beaux Arts style. Railway tracks entered the back of the building at the second floor over a massive viaduct and concrete bridge. The station included separate white and “colored” waiting rooms, a concourse, a train platform, and a second-level ticket office. The street level was home to businesses such as Atlas Confectionary and Lunches (1907); offices for Isaac and Moses Thalhimer (1910), the family that created a regional chain of department stores; and the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (1925-1926).

Another block of West Broad, featured in a postcard sent in 1922.

Meanwhile, the lots at 815 and 817 Broad Street awaited their ultimate purpose.

In 1925, finally, a birth on Broad Street’s side of Broad Street: The utilitarian brick structures that endure today at 815-817 West Broad appeared in the Richmond City Directory as new and vacant. The next year, they were occupied by the United States Navy Recruiting Station and also by a United States Navy Reserve Armory.

In 2004, Nancy W. Kraus applied to get this section of Broad Street included on the National Register of Historic Places, arguingthat when first built, 815 and 817 were streamlined and linear, but years and layers of paint clogged and covered the façade’s ornamentation. She asserted that 815 and 817 were this part of the street’s singular representative of art deco—perhaps hard to see now, given all the changes here. Within a few years, for example, the military center moved farther downtown and 815 was gobbled up by 817, then in use as a branch of the Toledo Scale Company.

The Sanford family who owned Toledo Scale may have known about a banner series of days for Virginia and African-American music that took place between October 13 and 18, 1929. Players from across the state flocked to the Richmond branch of the Atlanta’s James K. Polk Furniture Co., 803-805 West Broad, where they presented their work for engineers of the New York City–based OKeh Record Company. (Recordings of the event are available on Virginia Roots: The 1929 Richmond Sessions, released in 2002.) As Washington Postwriter Eddie Dean described the participants, “Uptown and backwoods, white and black, they were a motley gaggle of performers gathered in the heart of the Jim Crow South, carrying on a long musical tradition of defying segregation.”

Soon after, the Depression hit. In 1937 more storefronts stood empty than ever before or since. But the Sanfords and Toledo Scale kept their measure; the Sanfords rode out the lean years by bringing complementary businesses into 817. In 1932, for example, they joined with the Hobart Sales Agency of “food preparation machines”—whatever that category entailed.

A couple of enterprises particular to Richmond rose up nearby. First, at 818 (the north side of the street) came the ABC Hat Cleaning Company, which gets a small “c” in the city directory. In the racial shorthand of the day, that meant “colored.” The owner, Moses Winston, was for years the single African American businessman on the 800 block of W. Broad St. ABC’s business embraced all hat care, including dye and blocking.

Next door to us, at 819, the Orkin “Rat Man” polished his traps. And across the street again, the Chiocca family of restaurateurs opened their first of several establishments in Richmond. In the 1930s, several dance studios under various guises flitted in and out of 801. And during the last hour of March 22, 1938, the final streetcar took a sentimental run from Ashland to the Richmond station at Laurel and Broad, within spitting distance of number 817.

As the Depression ended and the Second World War began, the block got yet another makeover, embracing a hodgepodge of businesses: the glamorous Richmond Theater Guild and the Electrical Appliance Company, radio wholesaler The Arnold Company, Richmond Post No. 1426 of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and the business offices of Pine Top Poultry Farms. More apartment dwellers came in 1944, and so did photography studios. Around 1941, Harvey Sanford, Sr., died, leaving Toledo Scale to widow Kathy and son Harvey, Jr. The Sanfords soon disappeared from the city directories, but Toledo Scale stayed at 817 until 1954, when Park Accessory, a wholesaler of automobile parts and additions, went in.

Richmond in 1864, part of a map of battlements found in the Library of Congress. Broad is the railroad street that runs between the “I” and “C.”

The block was definitely becoming more blue-collar. While 817 offered motor parts, 801 became home to the Formosa Restaurant of Joung Chung and Bing Woo, who advertised, “Real Chinese Food!” and also a variety of labor and union groups: The Richmond Building Trades Council; the Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators and Paperhangers of America Local Union 1018; Sheet Metal Workers International Association Local 15; Operative Plasters and Cement Masons International Association of United States and Canada Local 64; the International Union of Operating Engineers Local 147; the Asbestos Workers Union Local 88; and the Firefighters Union Local 995. At 801, too, were organizations for plumbers and steamfitters, bridge and ornamental iron workers, stage employees, and motion picture projectionists.

In 1968 the ABC Hat Cleaners vanished from the directory, but the 800 block enjoyed a taste of urban renewal beginning in 1969. Vincent T. and Jean A. Gilligan moved their book shop into 808. At the former ABC Hat Cleaning location, the block got a taste of the limelight through Top Star Productions and Reed Enterprises, and at number 819, Glisson Motion Pictures Equipment. Nickel Bag Novelties started sharing space with Reed Enterprises in 818, and a Goodwill store arrived at 809.

The university was beginning to make its presence felt on the block: In 1975, building 801 was occupied, briefly, by Joy Massage, where apparently more than a few VCU students worked. Number 803 underwent another transformation into what became a music club of some notoriety called The Pass — “basically a get-puke-drunk rock club,” one former patron remembered with some fondness. A steep entrance stair required those at the top to shout out, “Coming down!” They hosted up-and-coming bands such as Squeeze and the Police, back in the days when musicians had to haul their own equipment up that perilous stair.

Legendary and much-loved Richmond institutions from this era have endured. At number 821, the Adams Barber Shop started catering to what at first must’ve been a shaggy-haired clientele, but the owner still gives clean-as-a-whistle short cuts today—a member of the Broad Street board is a regular. The more prosaic Richmond Glass company remained at 814-816 until 2009.

Other changes came rapid-fire. From 1987 to 1990, number 801 served as the creation space (a.k.a. the Slave-Pit) for the Richmond metal opera art collective GWAR. In 1988 Craig Hartman brought his Hartec cabinetry business to 817, and 815 (separated again) became apartments. But by 1992, Hartec and Hartman were replaced by Getchell Signs. The Aladdin Express Restaurant came into 801, the offices of Bellona Arsenal Farm (a breeder of animals such as lemurs, camels, wallabies, and guenons) went into 813, VCU clinical psychiatrist Renata Forssmann-Falck, M.D., hung out a shingle at 819, and Velocity Comics brought superhero flair to the storefront, where it remains Broad Street’s next-door neighbor. Way Cool Tattoo went into 823.

Mr. Adams in the barber shop he owned and operated for over 30 years. He has closed his shop as of 2018, but he still cuts hair.

And finally, near Adams’ Barber Shop and next door to Velocity Comics, across the street from the used-book store and a brand-new Dunkin’ Donuts, we come back to 817. VCU started leasing the property in 2005 and moved in its Student Media Center. Since then, numbers 815 and 817 have housed student apartments above, student creativity below, under the direction of local media guru Gregory Osina Weatherford. Mr. Weatherford has now moved on to the State Council of Higher Ed, but he—as much as any of these historical figures—has left his mark on our block of Broad Street. And this issue is a fitting tribute to him.