“Far from the cemetery here in Zwammerdam, far from the hole they have already begun to dig …”

A Dutch orphan survives abuse, emigrates to America, and dies of malaria while fighting in Cuba–all within twenty-one years. This third installment of the “Family Laundry” series sees Luanne Castle imagining a mother, long deceased, writing her son’s life story.

“More Burials” itself can be downloaded and printed as a broadside, or you can scroll down to read it in plain text.

The “Family Laundry” series traces Luanne’s ancestry in poems and short prose — with photographs, newspaper clippings, and other source materials: the small things from which a writer has pieced together family history.

**********************

Click here to read Luanne’s introduction to the series.

Click to read the first poem, “An Account of a Poor Oil Stove Bought Off Dutch Pete.”

And here is the second piece, “What Came Between a Woman and Her Duties.”

Image: Gerrit (Gerard) Leeuwenhoek (1877–1898) is the subject of his mother’s tale in Luanne’s persona prose-poem.

This feature is available in slightly different format on Medium.

********************************************************************************

********************************************************************************

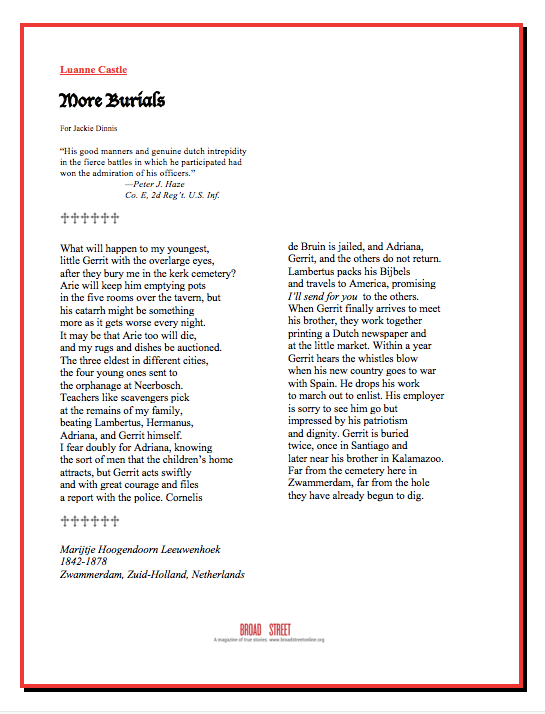

More Burials

for Jackie Dinnis

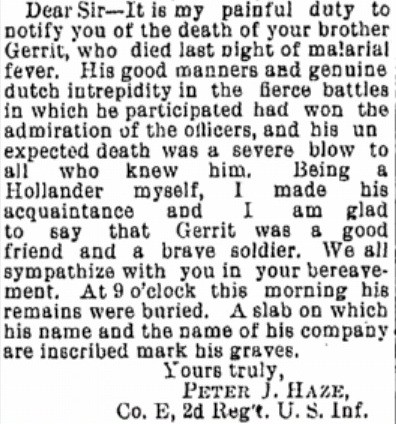

“His good manners and genuine dutch intrepidity

in the fierce battles in which he participated had

won the admiration of his officers.”

—Peter J. Haze

Co. E, 2d Reg’t. U.S. Inf.

— — —

What will happen to my youngest,

little Gerrit with the overlarge eyes,

after they bury me in the kerk cemetery?

Arie will keep him emptying pots

in the five rooms over the tavern, but

his catarrh might be something

more as it gets worse every night.

It may be that Arie too will die,

and my rugs and dishes be auctioned.

The three eldest in different cities,

and the four young ones sent to

the orphanage at Neerbosch.

Teachers like scavengers pick

at the remains of my family,

beating Lambertus, Hermanus,

Adriana, and Gerrit himself.

I fear doubly for Adriana, knowing

the sort of men that the children’s home

attracts, but Gerrit acts swiftly

and with great courage and files

a report with the police. Cornelis

de Bruin is jailed, and Adriana,

Gerrit, and the others do not return.

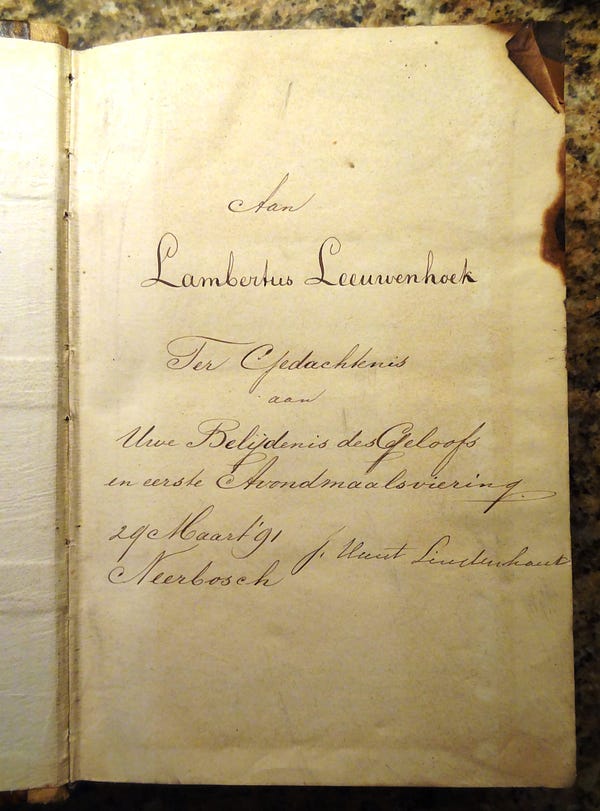

Lambertus packs his Bijbels

and travels to America, promising

I’ll send for you to the others.

When Gerrit finally arrives to meet

his brother, they work together

printing a Dutch newspaper and

at the little market. Within a year

Gerrit hears the whistles blow

when his new country goes to war

with Spain. He drops his work

to march out to enlist. His employer

is sorry to see him go, but

impressed by his patriotism

and dignity. Gerrit is buried

twice, once in Santiago and

later near his brother in Kalamazoo.

Far from the cemetery here in

Zwammerdam, far from the hole

they have already begun to dig.

— — —

Marijtje Hoogendoorn Leeuwenhoek

1842–1878

Zwammerdam, Zuid-Holland, Netherlands

Gouda, Zuid-Holland, Netherlands

********************************************************************************

Luanne Reveals Her Sources and Process

I didn’t come to Gerrit and his mother, Marijtije, right away. Their story is one of those you find while you’re researching someone else.

When my grandfather told me family stories, one of his favorite characters — and therefore mine — was his Uncle Lou, a shopkeeper. Uncle Lou was born Lambertus Leeuwenhoek, a descendant of the same Leeuwenhoek family that produced the inventor of the microscope.

Uncle Lou was ours by marriage. His wife was Grandpa’s Aunt Jen DeKorn, one of the three children of Richard DeKorn and his wife, Alice Paak DeKorn, who carried the burning oil stove in my poem “An Account of a Poor Oil Stove Bought Off Dutch Pete.”

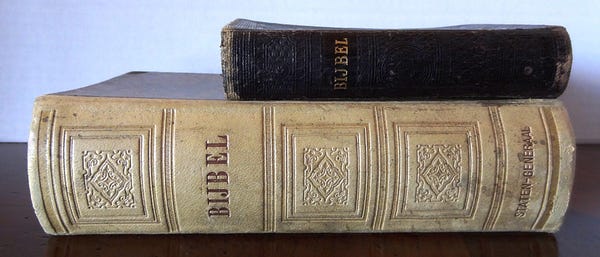

When my grandfather passed away, I was left with (among much other family history) his stories about Uncle Lou, two Bijbels (Bibles) that he had brought with him from the Netherlands, and a handful of photographs.

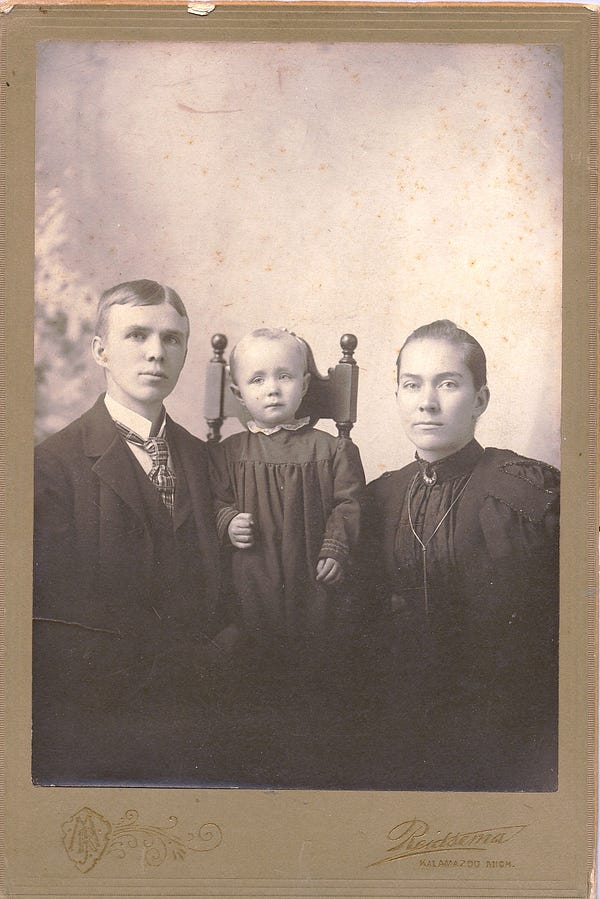

Two of the antique family photos that Grandpa had identified for me were of Uncle Lou’s brother, Gerrit — someone I’d never heard of.

Above: Lou, Alice, and Jennie Leeuwenhoek.

Below: the spines of two family Bibles in Dutch.

I was surprised and intrigued to find that Uncle Lou had had a brother. Grandpa had told me that Uncle Lou was an orphan, so I had grown up imagining him all alone in the world. But when we went through the photos and Grandpa identified Gerrit and Lou’s relationship, I realized that Lou had not been alone: he came from a family. And from even more family than I’d thought — I discovered that there had been seven siblings in all. I wondered about their stories.

As an aside, I also thought Gerrit was a very handsome young man.

A floodgate opened after I published some facts about Gerrit on my blog, The Family Kalamazoo. A man in the Netherlands, an amateur genealogist called Adriaan Leeuwenhoek, contacted me. He, too, was researching the history of the Leeuwenhoek family.

Over the next few months, our exchange of information was invaluable and absolutely fascinating. That is how I learned about the orphanage at Neerbosch and how Lou and Gerrit and their siblings landed there after the death of both parents.

Here’s what I know now about Gerrit’s family: Marijtje, his mother, was born on August 8, 1842, in Zwammerdam, Zuid-Holland, Netherlands. She married Arie Leeuwenhoek on April 29, 1864, in Hekendorp, Zuid-Holland, Netherlands. They had ten children in twelve years; however, I believe only seven survived. Gerrit was born on 24 January 1877 in Gouda.

——

Marijtje died on March 3, 1878, in Gouda, Zuid-Holland, Netherlands, at the young age of thirty-five. Gerrit was still a baby. Arie, a tavern owner, died eight years later, which is why the couple’s four youngest children were sent to an orphanage at Neerbosch. (The three oldest were already adults.)

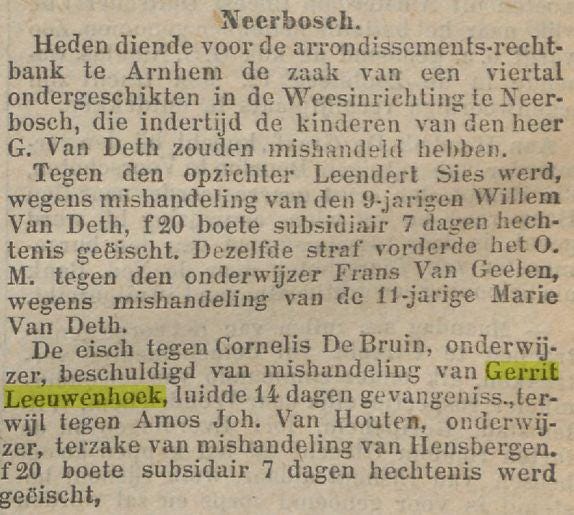

That orphanage was a terrible place. Adriaan Leeuwenhoek shared with me newspaper articles about the cruelty inflicted on the children there. The articles indicate that the court prosecuted four cases of the mistreatment of children at Neerbosch.

Superintendent Leendert Sies abused nine-year-old Willem van Deth, and teacher Frans van Geelen assaulted eleven-year-old Marie van Deth. Another child was abused as well, but the Google translation gets murky there.

The third victim listed is … Gerrit Leeuwenhoek. It was in part thanks to him that the orphanage staff were brought to justice. Although Gerrit wasn’t my blood relative, I felt proud when I read that he had had the courage to report an abusive teacher to the police.

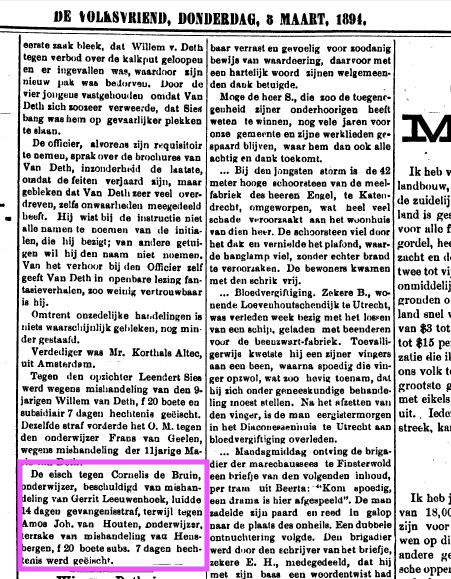

Cornelis de Bruin was given a fourteen-day jail sentence for assaulting Gerrit. The case was even important enough that De Volksvriend, one of the various Dutch-language newspapers in the U.S., reprinted the account of the trial.

The account was reprinted in De Volksvriend.

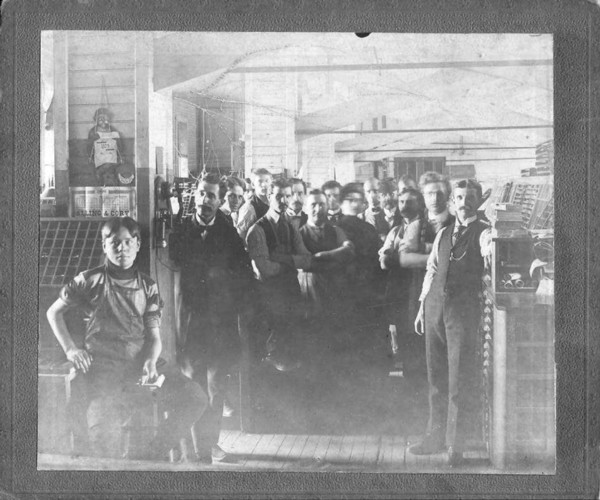

The account was reprinted in De Volksvriend.Incidentally, the Dutch Reformed church advocated that immigrants keep the Dutch language alive in newspapers like De Volksvriend. Some of my relatives worked for such a paper,called Hollandsche Amerikaan. It was founded in 1890 as a tri-weekly, eight-page newspaper. It was published in Kalamazoo, Michigan, with a circulation of 1,500. The editor in 1899 was P.A. Dalm. I’m not sure if the people in the photo to the left were paid employees or volunteers.

Above: Luanne’s relatives are among the printshop workers pictured here in 1899.

——-

The more Adriaan and I discussed the orphanage situation and the more information I collected, the more I began to imagine what it must have been like for the Leeuwenhoek boys and perhaps especially their sister, Adriana, when they were left orphans. I also imagined how this led Lou and Gerrit to emigrate from the Netherlands to begin new lives.

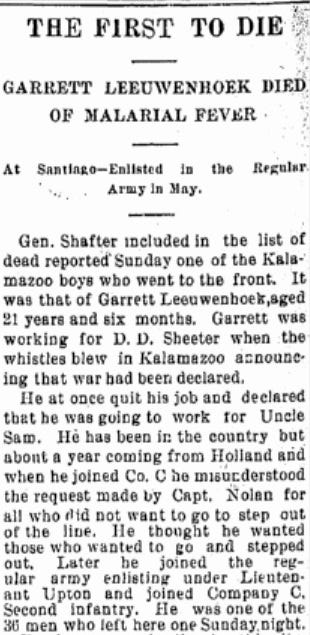

Gerrit grew up to be a war hero in the United States. He fought in the Spanish-American War and died of malaria in Cuba at age twenty-one. He was praised for his bravery — perhaps a natural outcome of his bravery as a child.

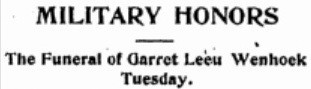

Gerrit’s obituary of 2 July 1898 mentions family, Dutch loyalty, and good reputation.

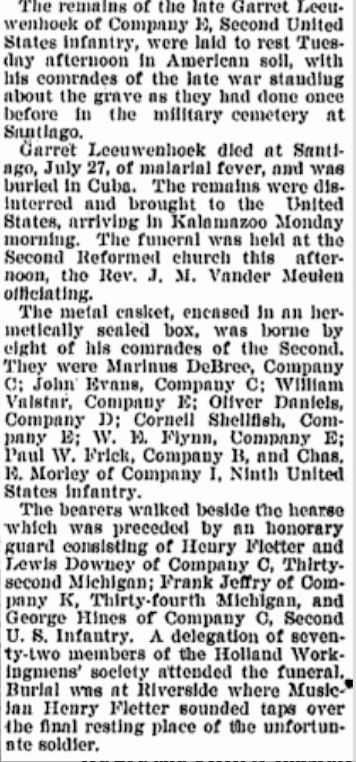

Below: His funeral on home soil was reported on 5 April 1899.

One of Gerrit’s commanding officers wrote of his bravery, and the letter was published in newspapers.

——-

There is a lot in Gerrit’s story to appeal to a writer. As a mother, I naturally thought about how horrified Gerrit’s mother, Marijtje Hoogendoorn Leeuwenhoek, would have been if she had known what happened to her children after her death.

As I imagined my way into a piece about them, I asked myself a big question: What if Marijtje could see what was happening to her children after she died?

And … Who better to tell the story than the person who would be most invested in the fate of the children she had borne and raised as long as she was able? So Marijtje’s voice came to me, recounting the life of her remarkable son.

********************************************************************************

Luanne Castle’s Kin Types (Finishing Line Press), a chapbook of poetry and flash nonfiction, was a finalist for the 2018 Eric Hoffer Award.

Luanne’s first collection of poetry, Doll God, won the 2015 New Mexico — Arizona Book Award. Her poetry and prose have appeared in Copper Nickel, Verse Daily, Lunch Ticket, Grist, River Teeth, The Review Review, Phoebe, and other journals.

Luanne reconstructed much of her family history by starting a blog, The Family Kalamazoo, and she continues to add to her knowledge of her ancestors through readers and other good souls met online.