“In the past, Mrs. Culver has been aided and abetted by her female friends in the art of painting …”

BROAD STREET presents the second installment of a series tracing Luanne Castle’s ancestry in poems and short prose — with photographs, newspaper clippings, and other source materials: the small things from which Luanne has pieced together family history. “What Came Between a Woman and Her Duties” was first published in Copper Nickel in March 2017; we present it here with the materials that make the genealogy of the work.

The piece itself can be downloaded and printed as a broadside, or scroll down to read in plain text.

Click here to read Luanne’s introduction to the series.

Click to read the first poem, “An Account of a Poor Oil Stove Bought Off Dutch Pete.”

************************************************************************************************

**********************************************************************************************

What Came Between a Woman and Her Duties

14 May 1897

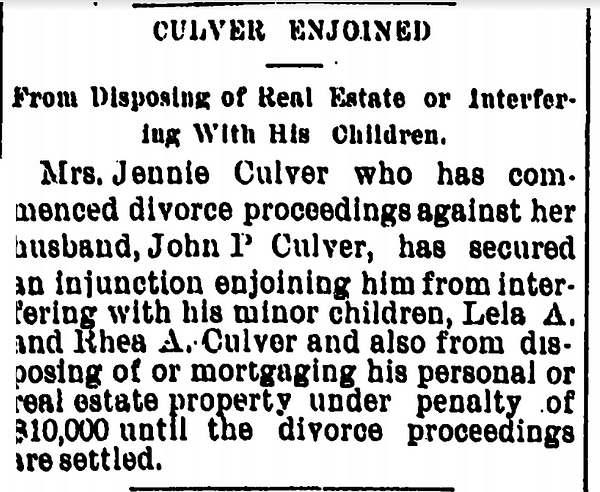

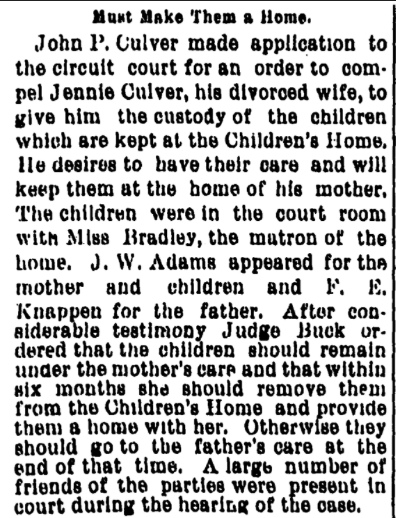

On this Friday, in our fair city of Kalamazoo, Recreation Park refreshment proprietor John Culver has applied to the Circuit Court to gain custody of his two young daughters from his divorced wife. The girls currently reside in the Children’s Home. They were accompanied to court by Miss Bradley, the matron of the Home.

Mrs. Culver, the divorcée, and the children were represented by J. W. Adams. The father was represented by F. E. Knappen. Mrs. Culver, pale and stern-looking, wore a shirtwaist with tightly ruched collar and generous mutton sleeves. The strain of her situation shows clearly on her visage. In the past, Mrs. Culver has been aided and abetted by her female friends in the art of painting, as an article of 6 February 1895 in this very daily can attest.

A large number of friends of both parties were in the courtroom and heard emotional pleadings on both sides. Judge Buck ascertained that Mrs. Culver is engaged in the pursuit of an honest living at this time and so ordered that the children remain in the mother’s care. She was given six months to bring them home from the orphanage or they will go into the care of their father and his mother. Let us hope that Mrs. Culver can stay away from the easel.

—Reprinted from Copper Nickel.

*************************************************************************************

Luanne Reveals Her Sources

“Were they running from Kalamazoo, from scandal, from John Culver — or toward a new world?”

Jennie DeKorn Culver

My fascination with Jennie came about for three distinct, but possibly interrelated, reasons: a divorce, a long-distance move, and the gift of an easel.

Jennie was my great-grandfather’s sister, someone about whom little is known but whose story has intrigued me largely because of its gaps. She has been difficult to research, in part because she moved away from her family after divorcing her husband, never (apparently) marrying again — and in part because her name is common.

Jennie was my great-grandfather’s sister, someone about whom little is known but whose story has intrigued me largely because of its gaps. She has been difficult to research, in part because she moved away from her family after divorcing her husband, never (apparently) marrying again — and in part because her name is common.

She was born Adriana DeKorn. As with many Dutch girls formally named Adriana, she was nicknamed Jennie. She may have been born in 1861 in Ottawa or Holland, Michigan, but I have not yet found her birth certificate or baptism in the U.S. Dutch Reformed Church records with other family members’

The dates I have found range from 1857 to 1861, with 1861 the most likely. If so, she died at age 86 on 7 April 1947 in Fort Steilacoom, Pierce, Washington — far from her birthplace.

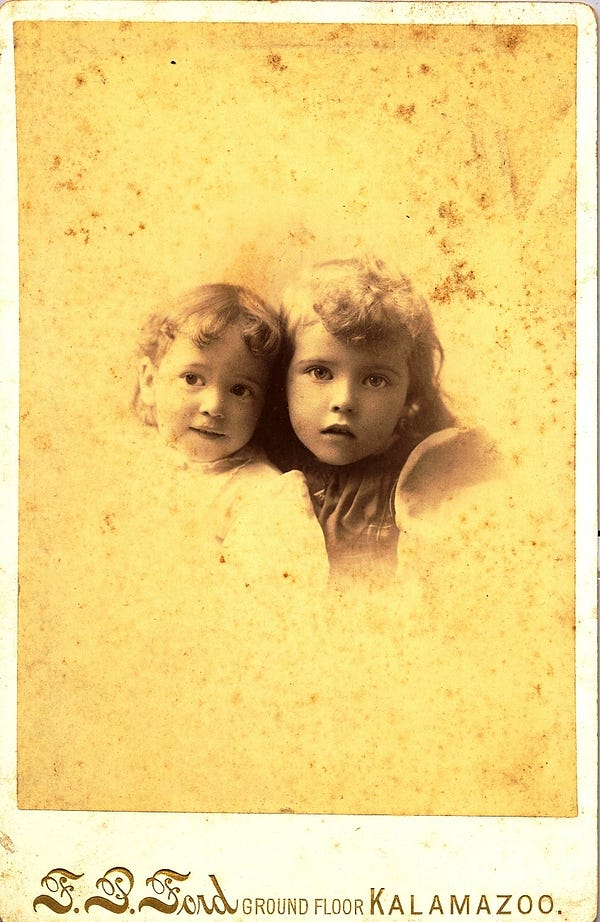

Above: Jennie’s two children with John Culver were Lela and Rhea.

When Jennie was three (assuming a birth year of 1861), her mother died. When she was twelve, her father passed. That would have left her older sister, Mary, and her brother, Richard, to take care of her. Richard was the oldest and the only male, so he would have been in charge of the family. Richard was my great-great-grandfather (the husband of Alice Paak from “An Account of a Poor Oil Stove Bought Off Dutch Pete”).

Jennie married John Culver when she was twenty-one. What was her life like before that? Mary and Richard had already been married a year when their father died: Richard married on 10 May 1872, Mary on 4 October 1872. Where did Jennie live then? I haven’t been able to find out yet.

I know more about Jennie’s life after she married John and had two daughters, Lela and Rhea, with him. Her marriage was unhappy, and she ended up divorcing John.

When I learned of that divorce, I was shocked. My Dutch Reformed ancestors did not get divorces. They tended to remarry after the death of a spouse, but they stuck with the marriage to that death.

I found articles in the Kalamazoo Gazette about their acrimonious split and John’s apparent unwillingness to support Jennie and the girls.

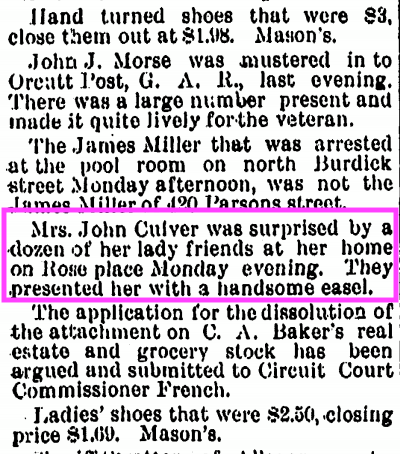

I discovered that Jennie wasn’t an old-fashioned housewife. She was also an artist.

I know about Jennie’s art because I found a newspaper column — “Jottings” from the Gazette, 6 February 1895 — announcing, among many other tidbits of news and advertising, that her friends had “presented her with a handsome easel.”

When I found that brief mention of Jennie’s easel, I could feel her heart beating in my own. How did she negotiate raising a family, dealing with a husband and then ex-husband, and make a living when her talent lay with the brush and canvas?

Unfortunately, none of her paintings seem to have survived.

The gift of an easel, in The Kalamazoo Gazette, 6 February 1895.

“Jennie was an artist and a divorcee at a time when it was difficult to be either .”

Eventually, Jennie moved to Seattle with her adult daughters. I started obsessing about that move. What would prompt three single women to travel to the wilds of Washington more than one hundred years ago? Were they running from Kalamazoo, from scandal, from John Culver — or toward a new world?

Because everything I had discovered from my own research led to a dead end in Seattle, I worried about them and constructed fantasy stories. Did Jennie run a boarding house? Were any unidentified men in their lives? Were one or more of the women lesbians?

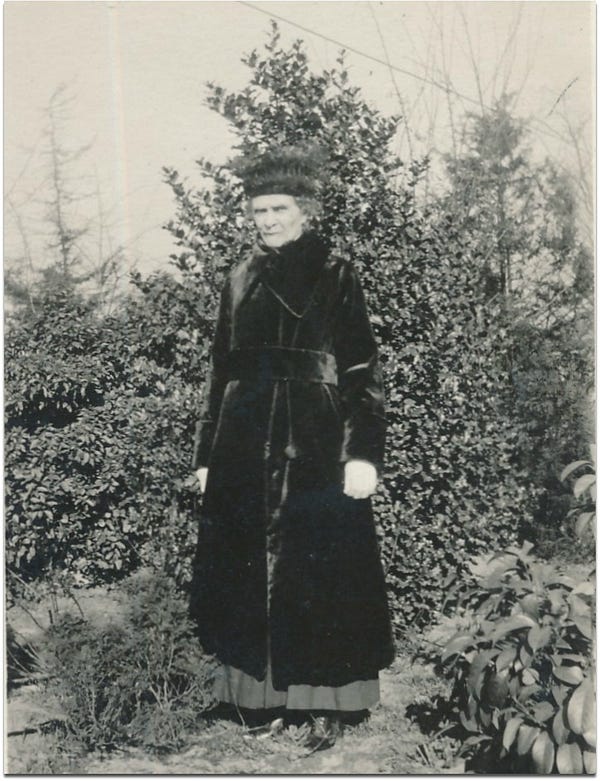

I haven’t found out what Jennie did in Seattle, but I do know that she died there in 1947. Based on the photographs I have, I think she lived well (wearing a beautiful fur coat in a few photos), as did her daughters. One daughter was a teacher and the other a bookkeeper.

A middle-aged Jennie in a fur coat.

My grandfather is the one who gave me the photograph of young Jennie and the one of her two daughters, Lela and Rhea, as children. He knew nothing of what happened to his great-aunt after her move.

However, I now have many more family photographs because a stranger read my blog, The Family Kalamazoo, and realized that my request for information about a Jennie Culver who moved with her two daughters from Kalamazoo to Seattle was something she could partially answer. This reader’s father had been a janitor for a retirement home in the Seattle area and had found a photo album out at the curb with the trash twenty-five or thirty-five years ago, and he’d saved it. Eventually it made its way to the daughter who happened to find me asking about Jennie online.

She mailed me the scrapbook, and suddenly I had many snapshots of Jennie’s daughters and some of Jennie herself. Some of the photos are from Kalamazoo and some from Seattle. There are also travel postcards. These are the photos that, when I was thinking about writing something on Jennie, gave me insight into the lives of the three women after they moved away.

Interesting note: when Jennie’s daughter Lela was a young lady she was in the paper as part of a Methodist Episcopal class, so perhaps Jennie herself had left the Reformed church.

Sometimes more questions arise the more answers I find.

What I do see clearly is that Jennie was an artist and a divorcee at a time when it was difficult to be either.

When I say the three surprising aspects of Jennie’s life — divorce, move, and art — may be interrelated, I mean that it is possible that being an artist led to her divorce, which then led to her eventual move to Seattle, far from family and friends other than her daughters.

From all these thoughts and questions, I began writing “What Came Between a Woman and Her Duties.” The newspaper article format came about as a way to prevent my own emotions from making Jennie a figure of pity or a victim, and to allow the reader to form her own opinions of Jennie’s situation.

*********************************************************************************

Luanne Castle’s Kin Types (Finishing Line Press), a chapbook of poetry and flash nonfiction, was a finalist for the 2018 Eric Hoffer Award.

Luanne’s first collection of poetry, Doll God, won the 2015 New Mexico — Arizona Book Award. Her poetry and prose have appeared in Copper Nickel, Verse Daily, Lunch Ticket, Grist, River Teeth, The Review Review, Phoebe, and other journals.