“A monarch butterfly is a small being, less than the size and weight of a Post-it note. The monarch butterfly phenomenon, however, is enormously heavy….”

This feature is also available, in slightly different format, on Medium.

From “Rivals & Players,” Broad Street‘s Winter 2019 issue.

*

A Curious Migration

By Mary Quade

1970s

I remember them on everything — towels, coasters, school folders, T-shirts, posters, earrings, stickers, greeting cards, coffee mugs — orange and black and white wings symbolic of something, though I didn’t know what. I was just a kid, and they were, I remember, everywhere.

Except … they weren’t.

Now, decades later, when I go searching for the monarchs of the 1970s, I find few. Butterflies, sure. Lots of butterflies, many with psychedelic wing patterns not found on this planet. But not nearly as many monarchs as I recall seeing. When I search through what’s now antiques or collectibles or retro kitsch, I wonder where those monarchs went. Maybe I just made every butterfly a monarch in my mind.

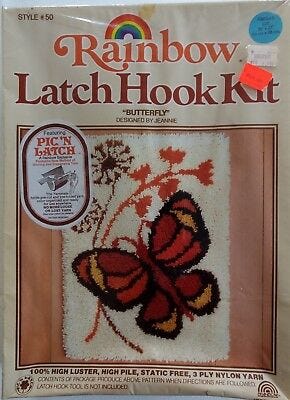

My sleuthing turns up a monarch on an old latch-hook wall hanging kit, that uniquely 1970s craft that had you using a metal hook to pull segments of yarn through a mesh backing to make a picture in a kind of shag rug. The latch-hook monarch design shows a fuzzy orange and black blob with some fuzzy tan and fuzzy yellow blobs. In the photo on the package, the finished piece hangs in what seems to be a kitchen. A ceramic crock sits nearby, filled with a few wooden spoons, a whisk, and a small strainer, but also with some dried stalks of weeds — a silly thing to store with one’s utensils.

The company that made it, Sunset Stitchery, also made embroidery kits. Several of them feature monarchs, including one showing the very same scene as the latch-hook hanging. The picture is much clearer when it’s not in shag; the yellow blobs are dandelions.

Incidental fact: Monarchs do visit dandelions, but the weed they gravitate towards most is milkweed. The milkweed’s leaves are the only food that monarch caterpillars will eat.

Weeds

When I think of weeds, milky or otherwise, a quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson sometimes springs to mind. It sticks with me not because I feel it expresses some meaningful truth, but because it was printed on the foil package of an herbal tea I drank every morning one summer in the early 1990s. The quote as I remember it is, “A weed is a plant whose use has not yet been discovered.” When I look it up to confirm my memory, it turns out that, as with the monarchs, I’ve remembered it inaccurately. Emerson wrote, “What is a weed? A plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered.” It’s a question and an answer, not a statement; a “virtue” and not a “use.”

Despite its poetry, the quote seems naïve. A weed is a plant that causes people a pain in the ass in some way or another. It pricks or stings or causes a rash , or it simply refuses to stop popping up where we don’t want it — in cracks in the driveway, in flower and vegetable gardens, in fields of crops, in lawns.

But almost all “weeds,” like all plants, have known virtues and even uses for humans. The leaves of pokeweed can be cooked and eaten, and pokeweed berries have been used as dyes and ink for centuries; it’s even listed on the American Cancer Society website as a natural supplement being studied for its possible anti-cancer effects. Lamb’s quarters make a nutritious spinach substitute, raw or cooked. Purslane is high in vitamin C and used for tart salads; you can buy the seed from tony gourmet seed catalogs if it hasn’t shown up on its own in your garden, as it has mine. Dandelions, of course, make good greens, and can also be fermented for wine. And so on.

Of all the weeds I can think of at the moment, milkweed seems the most virtuous, if virtue and use mean basically the same thing. The stem’s fibers can be used to make rope or fabric; the fluffy silk inside the pods, stuffing for pillows or mattresses — much like down, but hypoallergenic. The milky sap contains latex. A fact I come across again and again, one that seems truly virtuous, is that during World War II, milkweed silk was used as a replacement for the filling in life jackets, which was running low. Kids gathered the silk, and hundreds of tons of the stuff kept soldiers from sinking into the sea.

Here in Ohio, I’ve got a few acres of what I call “brushy field” on my property. Grass and crabapples and sumac and blackberry and goldenrod and Queen Anne’s lace. There are hundreds of trees we planted over a decade ago as tiny foot-long whips — pine, spruce, tulip tree, oak, maple, cedar — that now stand twenty to thirty feet tall. But some spaces we’ve left treeless, and there, I cultivate common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca. From the tall grass the stalks sprout in spring, with their broad, light green leaves, which in summer bear nodding clusters of rubbery orchid pink flowers, sweetly scented.

The opening of the star-shaped blossoms, or umbels, makes me think of a firework exploding in extreme slow motion, starting with a tight ball of buds that then flare out on tiny stems that droop with their weight. When the milkweed is blooming, the yard feels soporifically heavy with fragrance. Monarch butterflies appear, gliding from one tiny blossom to another.

Then, as the flowers fade, a few prickled pods develop along the stems, growing several inches long and tapered at the ends. When green, they are covered in fleshy spikes; as the months pass into fall, the plants dry and the pods turn velvety. Finally, they crack open, revealing tight layers of seeds attached to silk, which catch the wind and escape to drift across the field.

Prairie

My memory, of course, is now established as suspect. But I remember the 1970s and early 80s as a celebration not only of butterflies but also of dried plant matter, including ubiquitous bouquets of weeds in crocks. In Brownies, we wove hemp-y macramé hangers with beads like gallstones and wrestled corn husks into dolls.

In the garden, Mom grew lunaria, which we called money plant, also known as honesty. Its flat seed pods transformed into clouds of circular wax-paper-like “coins,” perfect for arranging in a clay jar and collecting dust. I also recall, somewhere in our house, a bundle of dried wheat in a beer stein, the wheat gathered from family land in Kansas. And a crock full of dried stuff stood next to our piano, which was in a high traffic zone; the weeds were always dropping bits as we shoved by. There was even a bag of dried stuff on the wall behind the bench where my sister and I sat at the kitchen table my dad had made by hand.

Maybe the dried plants grew out of the 1970s fondness for the prairie. The TV show Little House on the Prairie ran from 1973 to 1983 and featured hunky Michael Landon as Pa Ingalls and Karen Grassle as his oft-sunbonneted wife, Caroline (plus, of course, various girls playing Laura, Mary, and Grace, who were the focus of the books on which the show was based). Though her look on the show was fairly plain, Grassle exuded a kind of homestead hottitude, perhaps simply because of her proximity to smoldering Landon.

The prairie was sexy.

And so, apparently, were tiered and ruffled calico prairie skirts and high-necked, poufy-shouldered prairie dresses, trimmed sometimes with lace. Beyond fashion, the prairie popped up in kitchen appliances, in the popular hue Harvest Gold, Pantone color number 16–0948, that earthy brownish-yellow; the name is probably supposed to evoke grains like wheat or oats, but it’s pretty much the shade of dried weeds.

The prairie represented in Little House on the Prairie was mostly gone by the 1970s, and had been so for a long time. The government’s Homestead Act of 1862 invited settlers to the prairie, giving away 160 acres per claimant for a promise to build a house and farm the land. Ma and Pa Ingalls — the real ones, not just the fictionalized TV version — converted their section prairie to crops, as did my own ancestors, who were homesteaders in Kansas. The Ingalls family, however, built their little house on a Native American throughway on land not set aside for whites, and they had to move on.

Of all the prairie ecosystems that once thrived in the United States — 240 million acres — sources say only 3 percent remain today, the rest replaced by agriculture. In some states, it’s drastic. A map illustrating the vanishing prairies in Minnesota shows a big yellow swath bisecting the state from the northwest corner to the southeast edge, representing the prairies that existed from 1847 to 1908; those still around in 2017, marked in red, are speckles, amounting to only around 235,000 acres of the once eighteen million acres of tall-grass prairie.

I’ll admit, I can’t begin to picture what all that prairie must’ve looked like. I have a hard enough time grasping the area of my own 4.3 acres of land.

Of course, the Little House series wasn’t filmed on the prairie, but instead at Paramount Studios and various locations in California and Arizona, including Big Sky Ranch, where, years later, some of the television series True Blood was filmed, featuring the now more in-vogue vampires instead of passé pioneers.

A big-screen version of Little House on the Prairie is apparently in development by Paramount Pictures, though my efforts to pin down details prove much like my search for the 1970s monarchs. The director originally mentioned with the project when it was at Sony Pictures, David Gordon Green, directed the film Pineapple Express, the plot of which revolves around another weed: marijuana.

Migration

Milkweed is named for its sticky white sap, which oozes from the plant when the stems or leaves are broken. The sap is poisonous to most creatures, so anyone who nibbles on milkweed ingests the toxins and becomes poisonous as well.

This is handy for the monarchs. They depend on milkweed for existence. The butterfly lays eggs on the leaves, and when the eggs hatch after three or four days, the caterpillars nibble for ten days to two weeks, passing through five instar stages. The growing caterpillars — with their yellow, black, and white bands — remind me of little striped socks. After spending ten to fourteen days as chrysalises, summer monarchs — if they survive — emerge, mate, and lay eggs. They live two to five weeks.

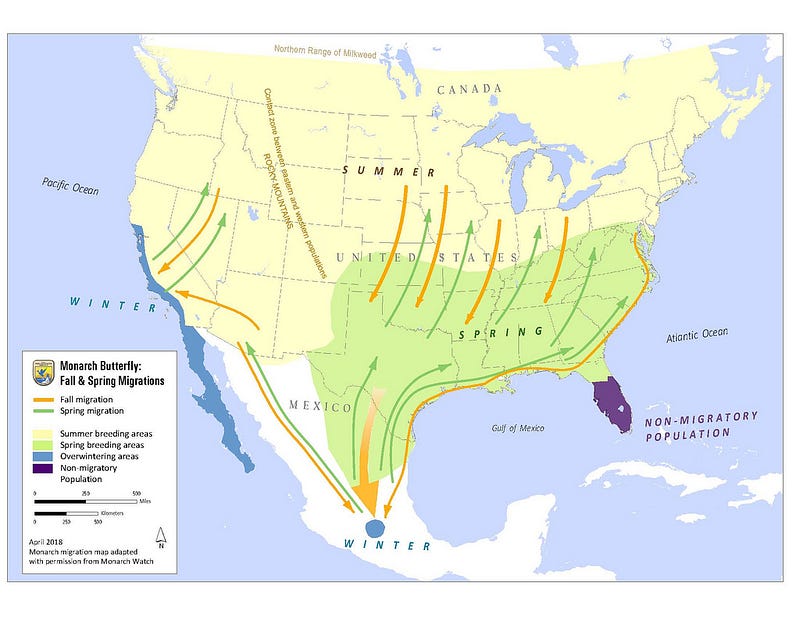

Unlike previous generations, the last butterflies to hatch east of the Rocky Mountains, known as the super generation, emerge in late summer and don’t mate, or not right away. Instead, they make the long migration over land to Mexico, where they winter in huge colonies in the mountains, clinging to trees en masse. Come March, they’ll begin flying north until they find milkweed upon which to lay eggs, which will become the first new generation of the summer, each making their way further to reach northern United States and Canada, milkweed by milkweed.

A monarch butterfly is a small being, less than the size and weight of a Post-it note. The monarch butterfly phenomenon, however, is enormously heavy.

Memory

Those monarch images I remember from the past must be hiding somewhere. I dig around the yard sale of the internet some more and discover a few. Stylized on a pale yellow coffee percolator. On a cotton dishtowel with other blue and yellow butterflies and some flowers I recognize as lupine, as well as some flowers I don’t recognize as anything. Across pale blue wrapping paper, encircled in the words Birthdays are sunlit times of joy and new beginnings. But where I encounter them the most is in clusters on glassware, orange wings bright, for sale on eBay and Etsy. In the end, though, I find many more owls and mushrooms (more seventies icons) than monarchs.

I also find floating around on the internet some articles about something called Project Monarch, which is decidedly not about monarch butterflies at all.

Instead, “Project Monarch” sometimes refers to an alleged government mind-control experiment run through the CIA’s Project MKUltra program. I skim some articles, eyes landing on phrases such as “trauma response” and “multiple personality disorder” and “slave” and “master” and “marionette programming” and “Illuminati” and “demon possession.” I linger over the number of Americans purportedly subjected to Monarch programming via drugs such as LSD — two million. According to one source, the subjects can be called up by handlers to perform tasks — like assassination — that they later won’t remember, and will commit perfunctory suicide if discovered.

One article suggests that the name “monarch” comes from the fact that monarch butterflies carry out a year’s migration cycle, through the multiple generations, as though programmed.

Souls

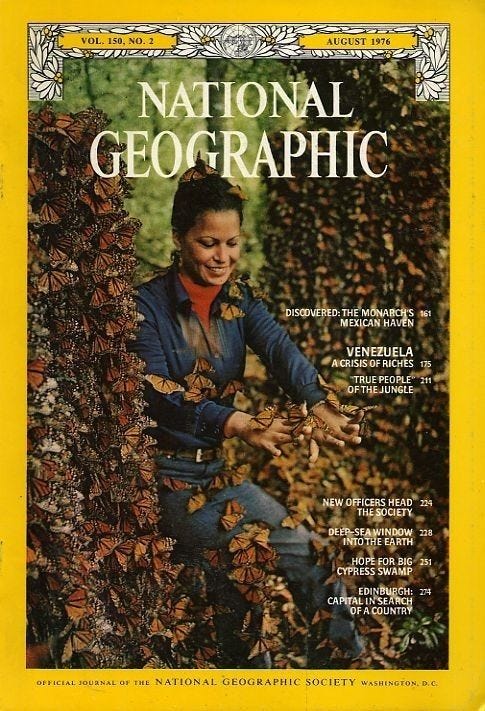

One image of monarch butterflies that I know passed before my eyes as a kid was the August 1976 copy of National Geographic. On the cover, a woman dressed in a blue denim shirt and jeans sits among thousands and thousands of monarch butterflies. Butterflies rest on her dark hair, pulled back in a bun. Butterflies cover her feet and lower legs. A few orange blurs of butterflies fuzz the foreground. The surface where she perches flutters with fragile wings. It seems that were she to move, she would crush hundreds, but she’s motionless, her arms stretched out before her, where butterflies land.

The woman is identified as Cathy Brugger. She was young and Mexican and married to an older American, Ken Brugger, with whom she conducted research. “Cathy” is what Brugger called her, but her given name was Catalina, and her name now is Catalina Trail. Until 1975, North American scientists had no idea what monarch butterflies did once they entered Mexico. All scientists knew was that the monarchs crossed the southern Texas border and then, poof, disappeared; where they went next was a mystery.

I’m fascinated by the existence of this hole in our understanding of something as ubiquitous as a monarch. Sure, there were some scientists trying to figure it out back then, including Canadian Dr. Fred Urquhart, who hired Trail and Brugger as research assistants. But what about the rest of us? Was anyone curious? Or were we just content to have the monarchs show up each summer, reassuringly reliable, like water from the tap?

In January 1975, Trail and Brugger found the monarch wintering grounds in the Sierra Madre Mountains. Millions of butterflies clung to the evergreens. The article by Urquhart accompanying the cover photo barely mentions Trail, except to say, “Ken Brugger doubled his field capacity by marrying a bright and delightful Mexican, Cathy.” Here, too, is a hole, something missing; she was more than just a pretty model for the cover.

I consider why the National Geographic article leaves out Trail’s role in locating the butterfly wintering grounds. According to an interview with Trail, she worked side-by-side with Brugger from the start, beginning in 1973, before they were married. But the article is written by Urquhart, a Canadian scientist who perhaps didn’t understand how involved she was in the search. Perhaps. Or perhaps he simply didn’t want to spread the credit around too much. Or perhaps because she was young and a woman and Mexican, she didn’t fit his idea of who belonged in the story — a story he might have felt he owned, since through his tagging, he had tracked the butterflies to Texas and projected the location of the wintering grounds in Mexico.

I want to admire Urquhart, but I’m put off by Trail’s absence in the article, and by one passage, in which he describes when he first saw the butterflies in Mexico, in 1976, a year later:

I had waited decades for this moment. We had come at last to the long-sought overwintering place of the eastern population of the monarch butterfly. Every wide-eyed child and meadow walker in the eastern United States and nearby Canada knows this colorful butterfly, by sight if not by name…But in winter the monarch vanishes from the regions. Where does it go? Until now, no one had known.

He makes it sound as if he were the first to realize the significance of the wintering grounds, not Trail or Brugger or the people native to the area, who had always noticed the clouds of monarchs each year as they arrived — an event that coincided with the Day of the Dead — and who believed the butterflies represented people’s souls.

Missing

In 2013, I was standing in my yard mid-July, staring out across the milkweed, when it occurred to me that I had yet to see a monarch that year. Usually they begin to show up early summer. Now their absence drifted across my brushy field, alighting on my consciousness. Where were they? Eerie, to have something usually so common now an omission in the landscape.

I knew about threats to their wintering grounds, such as logging and conversion of forest to agricultural land. A drought in the South of the U.S. wasn’t helping, either. But this seemed drastic, not a slow trickling away.

I found out that twenty years ago, the migrating monarch population in North America was one billion. Today it is less than a tenth that size.

In the Midwest, surrounded by animals, plants, and people who pull through tough winters and scorching summers, it’s easy to think of extinction as something that happens far away. We’re not fragile here. But of course, the passenger pigeon, once so plentiful the flocks would block out the sun, lost its battle with extinction here in the Midwest, the species dying out with the last bird in an Ohio zoo in 1914.

It’s easy to think of extinction as someone else’s fault, some tragedy brought on by things beyond our control, like the economic struggles of a poor nation far away. It’s easy, because then we’re off the hook and can watch, sad but guiltless, as, say, the Javan rhinoceros population (a.k.a. Sunda) dwindles to a few dozen, mostly killed for their horns. The last of the Vietnamese population of the species was shot in Cát Tien National Park in 2010 by poachers.

But look closer. The Sunda rhino owes much of its fate to the deforestation of Vietnam when U.S. troops used napalm and Agent Orange during the war. The chemicals already obliterated the rhino population to such an extent that in the 1970s, it was thought to be extinct.

Now, look closer at the missing monarchs, and you’ll find our love of cheap fuel. You’ll find hamburgers, chicken wings, hot dogs. You’ll find soda and candy and cookies. You’ll find T-shirts. Ethanol, animal feed, high-fructose corn syrup, oil, sucrose. Corn, soybeans, cotton, sugar beets. The United States grows around 84 million acres of corn alone. 73 million acres are planted to soybeans and 9.5 million to cotton. In 2014, the percentage of corn that was herbicide-tolerant was almost 90 percent, and the percentage of soybeans was 94 percent. Cotton was 91 percent. Herbicides kill weeds, and herbicide-tolerant crops can be sprayed with non-selective glyphosate and survive, allowing for widespread use on fields.

The weeds — including milkweed — become brown stalks suited to a 1970s vase.

When I think of these numbers, I try to envision the approximately 152 million acres of land in our country that are essentially weed-free. I can’t quite fathom it.

Of course, there are other herbicide-tolerant crops besides corn, soybeans, and cotton. One government statistic says that in 2013, 170 million acres of genetically modified crops were planted. That’s a significant chunk of the 240 million acres that were once prairie with weeds aplenty, including the monarch caterpillar’s only food, milkweed.

I look at the label of Enlist Duo, a glyphosate herbicide from Dow made for herbicide-tolerant Enlist corn. After involved general precautions (“Keep out of the reach of children,” “Avoid contact with skin”); and operator use precautions (“Keep and wash personal protective equipment separate from household laundry,” “After work, remove all clothing and shower using soap and water”); and physical or chemical hazard warnings (“This gas mixture could flash or explode”); and first aid (“Rinse skin for 15–20 minutes”); and toxilogical information (“No specific antidote”); and notes on environmental hazards (“Toxic to small mammals, birds, aquatic organisms and non-target terrestrial plants”); and statements about leaching (“The use of this chemical may result in contamination of groundwater particularly to areas where soils are permeable”) and disposal (“Do not reuse this container for any purpose”) — after all of these warnings and risks come two long lists of the seventy-five weeds Enlist Duo will eradicate, including lamb’s quarters, purslane, dandelion, and common milkweed.

None of this is a surprise to me — the toxic nature of herbicides, the vast species they can kill. Aren’t most of us aware of the dangers of chemicals? More aware even, perhaps, than we are of the virtues of weeds?

Virtue

What is virtue? The four Platonic virtues are temperance, wisdom, courage, and justice. In addition to these four “cardinal” virtues, the Catholic catechism espouses the “theological” virtues of faith, love, and hope. The seven heavenly virtues, in opposition to the seven deadly sins, include chastity, temperance, charity, diligence, patience, kindness, and humility.

Our general definition of virtue probably includes these principles, but everyone has their own variations on the theme of what is good. Benjamin Franklin was a fan of silence, cleanliness, and order, in addition to resolution, frugality, industry, sincerity, justice, moderation, tranquillity, chastity. and humility. The Romans, apparently, valued manliness and sternness, as well as humor. Hinduism appreciates freedom from anger and control of one’s senses, among other things. Buddhist virtues include equanimity, or balance in the face of life’s many contrasts, such as loss and gain.

When I consider these virtues, I think about the many I don’t possess. I also think that, except for silence and diligence, weeds have a hard time demonstrating any of these virtues.

Maybe, to address Ralph Waldo Emerson, “use” is, in fact, a better word. We’re the ones who may or may not be virtuous, and how we use something reflects our virtue or lack thereof. The seven deadly sins are lechery, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, and pride — several of which seem to drive how we use our land, or maybe how chemical corporations say we should use our land. Even while they tout the effectiveness of herbicide-tolerant crops, they admit that weeds are becoming resistant to glyphosate. Without new options, farmers use older, more harmful herbicides. Even if there were new options, one article by a DuPont agronomy research manager states, “Overreliance of any new weed management tool will eventually lead to its failure.” It seems a bit prideful to believe we can control nature without consequence.

Reserve

Catalina Trail and Ken Brugger encountered their first monarch wintering ground high on the steep peak of Cerro Pelon, located along the border of the states of Mexico and Michoacan. The area where the butterflies winter is now the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, a group of sanctuaries established by the government in 1986 in order to protect their habitat and currently encompassing over 139,000 acres and eight winter colonies.

By “created,” I mean the government imposed restrictions for land use on the people to whom the land belonged, the ejidos — collective land groups formed by the government in the years after the Mexican Revolution, consisting of the people who had once been peons working the land, earning little, and accumulating debt to the rich hacienda owners. The haciendas were clearly exploitive, demonstrative of several deadly sins.

While the ejidos certainly have their virtues, I find them confusing, parts of a messier system resulting from efforts to right some horrible wrongs, to enact some justice. For instance, not all members of an ejido have the right to own land or vote. The few that do, the ejidatarios con derechos, generally pass their rights on to the youngest son at death, leaving the younger members of a community without much say in the decisions of the ejido. I imagine that the ejidatarios with rights who live in the Biosphere Reserve must remember life before the reserve, and the younger community members without rights, don’t. If anyone is bitter about the impositions of the reserve, it’s most likely be those who can make decisions.

The ejidos that make up the butterfly reserve have limitations on their activities in the reserve, such as logging, which had helped sustain generations before the creation of the reserve. Some people still engage in illegal logging, cutting trees in what is known as the nuclear zone, where the butterflies winter, and elsewhere when they aren’t supposed to. The ejidosare quite poor, and while I’m frustrated at the loss of monarch habitat, I don’t think I can call such logging greed.

Encounter

It’s March 20, 2015, and I’m bumping along on a brown-and-white speckled horse, up and up and up a rocky trail, climbing the side of Cerro Pelon. I’m with my husband, Cris, and our guide, Vicente, a man in his thirties. We’re here very late in the season. The butterflies had left by March 21 last year. I’m not sure I’ll get to see what I’ve come here for, but these bright wings encourage me.

Vicente is from the town of Macheros, which lies at the foot of the trail and edge of the butterfly reserve.The horses belong to a man in town. Everyone in the community who wants to rent out their horses to visitors of the reserve is on a list; when their name is up, their horses go.

In Macheros, we’re staying with Vicente’s brother, Joel, who, along with his American partner, Ellen, runs a small inn. There are ten children in their family, and three of the five brothers have spent time in the United States, doing landscaping, factory work, and other jobs. I imagine their own dangerous migrations north, their returning home. Joel worked in a nail salon in New York, earning good money and generous tips, with which he built his house in Mexico. He returned to Mexico after eight years but then considered going back to the United States. When I ask him why he would take the risk of crossing again, he says that after all that time away, he didn’t feel like he belonged in Macheros. But then he met Ellen, who had come to see the butterflies, and they started their business of butterfly-related tourism. They hope if the village can see that butterflies bring as much income as logging, they’ll be more invested in protecting the Reserve. It has not, however, been the easiest sell. Investment in tomorrow is tough when you’re hungry today.

The horses snort and balk; the path is cluttered with tree roots and fist-sized rocks, and the horses’ hoofs slip occasionally, despite their careful footing. The trail zigzags along the mountainside, where tall evergreens stretch high around us.

Having worked in the United States, Vicente speaks better English than my Spanish, and we all chat back and forth in a mix of both. He’s a fun guy. He tells us a story about how when he was a boy his father took a family of tourists up the mountain, and on the way back down, one of the tourists, an older man, had a heart attack and died. The dead man was riding Vicente’s mare, and the news made him cry, because he worried something might be strange about his horse, now that a guy had died on her.

“My horse!” he says, laughing.

The dead man had been hospitalized before the trip but chose to come up the mountain anyway.

“At least he saw the butterflies,” Vicente says, and I’m not sure whether or not he’s being ironic.

About an hour and a half up the trail, he gets excited. “Do you see? Do you see?” I don’t. Then I do. An orange flutter on the edge of my eyesight. Then another, resting on the branch of a bush. Then more, flickering in the air along the trail.

A Gesture

It’s mid-July 2015 and 89 degrees. A few weeks earlier, the first monarch I’d spotted this summer had floated around the yard, visiting my milkweed, including a few stray plants coming up in a flower bed by the back porch. I’ve seen only one or two since then.

I’m pulling weeds — the kind in which I see no virtue — when I glance at one of the milkweed leaves. On it, about an inch long, a tiny striped caterpillar is chewing the most tender top shoot. A monarch-in-the-making.

I scan my brushy field, where the hundreds of milkweed plants are blooming and turn up a second caterpillar, the same size.

I look and look, but that’s all I find. Maybe these are the first.

The next morning my searching locates a third and a fourth, chewing their way through leaves in my garden and field. A single monarch flits over the field, landing on the floppy blossoms.

Part of me wants to coddle the caterpillars, pluck them with their leaves from the plants and keep them safe; the rest of me knows this would be only a gesture, and a small one at that. But I try to track the ones I see.

Two of the smaller ones disappear, long before they are large enough to transform into chrysalises. A third, larger caterpillar vanishes, and it may or may not have gone off to find a place to metamorphose. I want to think it has.

So I make a small gesture, and I put the last caterpillar inside in a large vase with fresh milkweed, set it on my porch, and watch it eat for a few days. A few nights later, it climbs to the screen I’ve stretched over the top, spins a little silk, drops down into a J-shape, and hangs there. The next morning, when I’m not looking, it transforms into a bright green chrysalis, with a row of tiny gold dots — a jade pendant. Inside, the caterpillar has turned mostly to stew. Were I to cut it open, I’d find black ooze. In under fourteen days, the chrysalis should start to darken, and the shapes of wings appear; at that point, it will be ready to open.

It turns out this one begins to darken just as we’re about to leave town. I take it outside and attach it to a small branch. When we return from our trip, a clear chrysalis hangs, broken open, butterfly-less.

Wonder

On Cerro Pelon, we dismount the horses and stare. There’s a cleared area where the trail widens, flanked by oyamel trees. In the trees, clusters and clusters of monarchs. The air is cool, and the monarchs are fairly still. They cling to the branches, their closed wings dangling, pale on the outside, so they appear covered in frost. When their wings open — a flash of the familiar orange.

A ranger approaches us on foot. It turns out he’s Vicente’s cousin, and he leads us over to a roped-off trail, a little farther down the mountain.

I hesitate, thinking about the purpose of the rope, rationalizing that this man is a ranger and wouldn’t do anything to harm the butterflies. But I worry he might just want to make a few tourists happy.

In the end, I duck under the rope, take just a few steps, and am surrounded by butterflies — in the trees, on the ground, flicking in the air. In places it is, in fact, very much like the picture in National Geographic, at least within the frame of my perspective.

I know the bounty is an illusion. The butterflies’ total Mexican wintering grounds has gone from 44.95 acres in 1996–97 to 2.79 acres in 2014–15. In 2013–14, it was only 1.66 acres, the size of a large suburban lot. So there’s been a slight rebound, of over an acre, but I can actually picture an acre, and it’s not very big. On land that totals fewer acres than my property, all of the migratory monarchs wait through the winter.

I’m not thinking about acres, though, in the moment. I’m thinking about the sound, which is the soft flutter of uncountable wings flapping. As the sun warms the trees, clouds of butterflies erupt into the sky, brushing my face and hair and arms. I’m horrified that I might crush them as I move. They’re both fragile and incredibly tough. Some of their wings are tattered. Some lie dead on the ground — many, Vicente tells me, males who have already mated and thus fulfilled their purpose, but also bodiless wings, victims of mice.

We linger in the oyamel for about two hours, alone with Vicente, his cousin, the sheaths of wings in the trees or transparent and illuminated in the air. Then another group of tourists approaches, and we head back down the mountain.

On the trail, we pass stumps of logged trees I’d noticed earlier. I ask Vicente about them, and he tells me that they were probably already dead when the trunks fell. I wonder.

Seeds

September. Monarchs begin migrating over Ohio, pausing in places along the edge of Lake Erie before continuing on. For a few days, I see them pass through my territory, flickers of orange along the road, heading south. Then, out in my brushy field, another caterpillar. I bring it in, put it in the vase, watch. It hangs in a J after just a day, and the next evening begins to transform from striped worm to green case.

Even as I watch this creature slip from one state to the other, its caterpillar skin splitting and writhing off, the change seems impossible. But I wait. And wait. Two weeks pass. The green chrysalis does nothing. I worry something has gone wrong. But since I don’t even understand what happens when things go right, I’m not sure what might cause things to go wrong.

A few more days pass, and then the chrysalis darkens. The next night, Cris and I watch as the butterfly emerges, a fat abdomen and wrinkled wings. She pumps her body, sending fluid into her wings, which unfold and hang, drying. Then she slowly opens them.

Male butterflies have black spots on their hind wings, so it’s easy to tell this one’s a female. In the brisk morning, with the temperature in the low fifties, I place her on the purple blossom of my butterfly bush before I head to work. She’s a late fall butterfly, bound all the way to Mexico, where she’ll winter, perhaps at Cerro Pelon.

She’s gone when I return, and the next day brings high winds from the north. I wish her luck.

***

After I release my butterfly, the United States Natural Resource Conservation Service releases some news. In November 2015, the government announces it will spend four million dollars to increase butterfly habitat in ten states along the corridor the butterflies travel: Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Ohio.

The basic idea is to encourage farmers (called “producers” in the release) to plant butterfly-friendly plants. It’s voluntary. Producers can learn more by reading a dense, chart-filled U.S. Department of Agriculture brochure titled, “Biology Technology Note № 78, 2nd Edition: Using 2014 Farm Bill Programs for Pollinator Conservation,” which features on its cover photos of two monarchs feeding on a pink-blossomed plant that is not milkweed.

Alternatively, farmers can read a more general brochure from the USDA titled “Monarch Butterfly Habitat Development Project,” which also has a monarch on its cover, feeding on a yellow flower that is also not milkweed. The goal of these programs is to increase the North American monarch population to 225 million by 2020, with an overwintering population covering 15 acres in Mexico.

If you read the more general brochure, you’ll find out that common, swamp, and butterfly milkweed are the most important milkweed plants for building monarch habitat. However, you also find out that it cannot be planted with crops or in pasture, because its milk mucks up machinery and makes livestock sick. So if producers are going to plant it, it will be on land that is part of “cropland retirement programs,” or land not in use for producing. The benefit to the producer will have to outweigh having the land in production; the land will have to be more useful to the producer as weeds. Considering this, I wonder if “sacrifice” is a virtue and if it is one producers embrace, whose name suggests they are defined by their products.

Though the monarch population hasn’t grown exponentially just yet, news of monarchs has. In an unscientific search of a library news database, I find 33 articles about monarchs in 2011, compared to 430 in 2015. The monarch is a popular cause, the butterfly a perfect spokesperson for conservation and caretaking — sweet and unthreatening, unlike the stinging pollinator bees, who are, in the end, much more useful. Many of the articles feature schools planting milkweed or folks raising caterpillars in their homes, I notice, not producers volunteering to bring back hectares and hectares and hectares of missing weeds.

The Fish and Wildlife Service could make all of this less virtue-reliant by listing the monarch under the Endangered Species Act, which is currently under review after a petition to categorize the butterfly as “threatened” was submitted in 2014.

But part of me wishes virtue could simply win out, that the prairie might be restored because of its own allure. Can’t we return to the sexy days of 1970s weed-worship, the lusty stalks whipping along the calico hems of ruffled dresses, hinting at strong thighs?

The decision about whether to declare the monarchs endangered, and thus to protect them, is due to come down in 2019.

Collection

It’s winter, and I’m driving through my little Ohio town, passing an intersection that holds an out-of-business carpet store, a gas station, a Baptist church, a candy shop.

Waiting for the light to change, I notice a black SUV pull to the corner of the candy shop parking lot, where a patch of weeds grows next to a split rail fence along the road. A woman climbs out. I assume she’s going to stick a sign advertising a yard sale into the ground, since yard-sale signs flutter on almost every corner around here.

Instead, she steps toward the patch of weeds — milkweed, I see now, the pods dry and gray. She snaps off a handful of stems and stuffs them into her backseat, then hops back in and slips away. The rest of the story I can only imagine.

Postscript

Since my visit to the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in 2015, Ellen and Joel have established a non-profit organization, Butterflies and Their People, which hires local people as full-time arborists to monitor the forest of Cerro Pelon and keep an eye on illegal logging. States such as Illinois and Ohio have implemented reduced mowing practices along their highways to encourage the growth of milkweed.

In summer 2018, possibly over 140,000 monarchs were tagged by citizen scientists to help track monarch population behavior and population health. In January 2019, the area of the overwintering sites in Mexico for 2018–19 was measured at 14.95 acres, the largest since 2006–2007. However, in 2018–19, the western population of monarchs that overwinters in California hit a record low of around 20,500 monarchs, down 86 percent from the previous year.

*******************************************************************************

Mary Quade is the author of two poetry collections: Guide to Native Beasts (Cleveland State University Poetry Center) and Local Extinctions (Gold Wake Press). Her awards and honors include an Oregon Literary Fellowship and three Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Awards.

Mary Quade is the author of two poetry collections: Guide to Native Beasts (Cleveland State University Poetry Center) and Local Extinctions (Gold Wake Press). Her awards and honors include an Oregon Literary Fellowship and three Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Awards.