The complicated quest to conceive.

“To be barren was like having leprosy …”

We used to joke about being barren. Before we started trying to have a baby, when we were just talking about it, my partner and I would see in everything signs that I was barren and laugh. To be barren was ludicrous, like having leprosy, so we laughed. An inexplicably empty wrapper in a box of wrapped straws at a take-out restaurant? Ha! I must be barren. A discarded old stroller on the curb? Barren, for sure. An empty fortune cookie? Yep, barren, and probably other ill-fated things.

There was in the medieval word something grotesquely amusing. I wasn’t just infertile. I was dried up and fruitless, like Hannah in the Book of Samuel. To be barren was biblical. It suggested a character flaw too; barren meant not just a woman unable to bear children but a woman unfit to be with child, unfit by God’s infallible decree. Then one morning I discovered this woman was me. We’d been trying to conceive for six months. We had my fallopian tubes x-rayed. We stopped the barren jokes.

It’s like the doctor said when I started crying: “It’s about children.”

He was right. It was about children. About having a family of my own with my partner, passing on my name, my genes. Having something little and helpless to love. Being enlarged.

“I understand,” he said. Except I don’t think he did, not altogether.

It’s about me too, this being-barren thing, about my body and how alienated I feel from it. How ashamed, too, when told it doesn’t work properly. It’s about being a woman and feeling that I’ve failed at that. About being thirty-six and worrying that I’ve squandered my chance to have children. About being gay as well, and fearing that might figure into this some strange how.

He looked like Sean Connery when he entered the crisp white exam room at New York’s Center for Human Reproduction to perform the hysterosalpingogram that morning, with his black eyebrows and frosty beard. And there was something about the way Dr. Arjunan (all names changed for privacy) put his two hands on mine that made me feel as if I were in a James Bond film, at once safe and uneasy.

He told me to lie face-up on an imaging table under an x-ray machine the size of an outdoor satellite receiver. Then, with a speculum and a long, thin tube he injected a contrast agent into my uterus. The x-ray took pictures of the dye’s journey through my fallopian tubes. It didn’t journey very far, and when I asked the doctor, “Is everything all right?” he didn’t give me an answer straight away, and then not what I’d call a straight one.

“It’s like a fish,” the doctor said of my right fallopian tube. “A fish with puffed up cheeks. Like this,” he said, inflating his cheeks. “And the left tube,” he said as he made a tight fist of his left hand and pointed at a squiggly line on the screen projecting the pictures, “is like a rose that never bloomed.” I looked at his closed fist. It didn’t look like a flower. And then he told me I had options: “IVF,” as if that were more than one option.

In the cab ride home my partner tried to console me. “What is infertility, anyway?” she asked.

No longer a laughing matter, barrenness was to be put into the proper perspective, put in its place. “Is someone who needs hormone medication infertile? Even if they have a baby? Are homosexuals infertile by default? I mean, is a nun infertile, Christine, for Christ’s sake?”

***

My plan to have a baby started out innocently enough. It began with a series of intra-uterine inseminations (IUIs) performed by a midwife in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, over the course of half a year. I didn’t know about my blocked fallopian tubes then. But the tubes matter. IUIs get the sperm in the uterus, but the fallopian tubes are still where the action happens, where the sperm must meet the ovulated egg. If the tubes aren’t welcoming, forget about it. (In in vitro fertilization, or IVF, on the other hand, the tubes are taken out of the equation and the sperm and egg meet in a lab dish.)

The midwife performed the IUIs with anonymous donor sperm my partner and I had chosen from a cryobank. My partner held my hand and looked lovingly into my eyes each time. The midwife, who had a yoga ball for a chair and shortened my name affectionately, came from the school that rejects medical arrogance and refuses to commit to assumptions or conclusions about anything reproductive.

“We just don’t know, Chris,” she’d say in answer to many of my burning questions, shrugging her shoulders and bouncing on her ball. I trusted her and wanted to bounce along with her; it was only after the fourth failed IUI that I told her I’d have my tubes examined and try a little acupuncture. “Love it,” she said.

I was right to be concerned. The numbers bear me out. One-third of couples in which the woman (or the woman trying to conceive) is over thirty-five have fertility problems, says the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. After she turns thirty-five, the number of eggs a woman has still stored in her ovaries drops precipitously. Her ovaries are less likely to release what few eggs are left, and the quality of the eggs is just not what it once was. A woman over thirty-five is more likely to have had an illness, infection, or other condition that can cause some form of infertility, including impassable fallopian tubes.

And yet more women are delaying childbearing until at least thirty-five. The proportion of women giving birth for the first time at the age of thirty-five or older jumped in the years 2000 to 2014 by almost 25 percent. The number of women needing technological intervention to get pregnant over that period doubled. The use of acupuncture to treat infertility in conjunction with IVF has also increased, with women buoyed by recent studies showing the two-thousand-year-old Chinese medical practice can improve IVF success rates.

Dr. Yen bills herself as an acupuncturist specializing in barrenness. A Shanghai University — trained practitioner of the Eastern medicine, she treats all sorts of causes of infertility — poor egg quality, hormone imbalance, thin uterine lining. Dr. Yen can even light a path through blocked fallopian tubes, she says on her website, but success depends on the cause and severity of the impediment, and can take months or even years of treatment.

I go to see her not to open my tubes but to boost my chances with IVF. Doctors of Western medicine won’t vouch for all the claims of acupuncture practitioners, but they do allow that the two treatments together might improve a woman’s chances of getting pregnant, if only by increasing blood flow to the uterus and relieving stress.

Dr. Yen’s office is opposite Carnegie Hall in midtown Manhattan, on the fifth floor of a building that also houses a second acupuncturist, a cosmetic surgeon and a voice coach. High-pitched peals from behind the door of the voice coach’s office fill the corridor. I swear I can also hear the groans of patients behind the doors of Dr. Yen’s treatment rooms, but white noise machines in her waiting room keep much of the torment from reaching my ears.

The door to the waiting room is always open, a nice touch, the pursuit of openness manifest at the threshold. A Chinese masseur sits stilly against the wall across from the door, his head bent in a book. His job is to give patients their pre-acupuncture rub-downs.

Greeting me is a receptionist, a sanguine Chinese woman in her twenties who sits at a desk to the right of the entrance. Sometimes she probes me with questions that seem indiscreet for a waiting-room crowd: “Have you got your period yet?” she calls out cheerfully from behind her desk.

“Yes,” I whisper. “YES,” I’m made to repeat. But I discovered early on it’s par for the course, this dropping of pretense, in the house of the broad-shouldered, no-nonsense Dr. Yen, where bluntness goes for kindness.

“No way a baby fit in there,” the acupuncturist told me on my first visit. She pressed down on my stomach as I lay on a massage table, horrified at how inexplicably right she sounded. “We loosen you up for baby,” she said, shaking her head as if the undertaking were beyond her. “You too tight, too tight.”

When exactly did things go awry? I wondered. When did I get too tight? When did my fallopian tubes get all twisted? I’d never thought twice about my tubes before, didn’t even know what they did. I believed they would go to work, doing whatever it is they do, when I summoned them. There was no tending to them the way my foremothers evidently tended to theirs. No keeping them plump and open and bursting with potential life like other, more womanly women apparently do. Was there a mysterious feminine hygiene routine my friends were taught in health class on the day I ditched to read The Outsiders? A quiet flushing out all real women ritually performed in the shower while I went about my days and years showering in culpable neglect?

And what about those years, huh? So many of them behind me now, aren’t there? Did my tubes simply run out of patience? Did they dry up and pack it in after waiting three and a half decades for me to contemplate the miracle of life? Or did things go wrong for me from the start?

Like the first “test-tube baby,” who was born two years after me, I was considered something of a miracle. I wasn’t conceived in a lab, but there had been intervention of a sort, the divine sort. My Catholic mom, sick with a rubella infection while carrying me, refused to terminate her pregnancy against medical advice. Doctors warned of severe birth defects. My mom went to church and prayed. That was all she could do, put her faith in God, she said. And it almost worked. On the day of my birth I might as well have been perfect. It was only a few years later that doctors discovered I was deaf in one ear, and maybe, just maybe, my fallopian failure is a congenital defect too.

Acupuncture is not, as I once thought, some softly soothing thing. At Dr. Yen’s there is no peaceful bamboo flute music in the background, no silly, sage grin on my face. This ancient Chinese medical practice doesn’t still the modern fretful heart, it hurts. With four treatment rooms, Dr. Yen can hurt four patients at a time. Each room has a massage table and a plastic bin for discarded needles. On the walls are prints of watercolor paintings. The artist has a penchant for painting birds in trees. Only birds in trees. On the walls, in addition to birds in trees, are three medical posters showing all the paths of the qi — the life force — in a man from the front, back, and side. When it’s busy Dr. Yen floats from one room to another, stopping at the reception desk to coat her hands in antiseptic solution and ask questions of the receptionist. She’s tall and loud, so it’s not floating so much as locomoting, and it’s not asking but rather barking those questions.

She barked at me: “You not Jewish, are you?”

I was in one of the rooms, begging her to go gentle on me, and she was scoffing at my weakness.

“No, I’m Australian.”

“English?” she guessed.

“Yes, and Irish,” I told her. “And a little Italian on my mother’s side. Why?”

“Jewish people take pain,” she said. “Japanese too. Irish and English, no. Italian, definitely no.”

I told Dr. Yen what the deal was. “My tubes are blocked,” I said. “The left one more than the right, but both basically blocked. Like fish.” I wished to tell her, too, how the fertility clinic that performed the tube test felt like a eugenics lab, how I was made to walk past rows of pale lab-coated researchers to reach a sterile exam room, how the instruments were metallic, how I was x-rayed and it felt all cold and impersonal, nothing like the simple, unadorned environs of this, my alternative healer. But I didn’t say any of these things. I just looked at her, my eyebrows lifted imploringly, waiting in expectant wonder for some unfathomable Eastern wisdom to pour forth and offer me comfort.

“You get IVF now,” the blunt one said instead, echoing Dr. Arjunan, and got to jabbing.

***

It turns out the Catholic Church considers not just abortion (such as the one my mother didn’t have) but also IVF to be a sin. Since the first IVF birth in 1978, more than five million babies around the world have been born as a result of the technique, and its pioneer earned a Nobel Prize in 2010. But the infertility treatment can result in surplus embryos, which are either frozen, destroyed, or donated to science for research. Destruction of embryos, the Church proclaimed in its 1987 document Donum Vitae (“The Gift of Life,” or “Instruction on Respect for Human Life in Its Origin and on the Dignity of Procreation”), is as abominable as abortion. Experimentation on embryos is a “crime against their dignity as human beings.” Even freezing embryos for possible future use is offensive. That an IVF baby is not the “fruit of marriage” makes the treatment sinful besides. And if a couple requires donor sperm or eggs, the Church says, such “recourse to the gametes of a third person … constitutes a violation of the reciprocal commitment of the spouses.” In other words, you’re cheating on your partner.

Allowing infertile or post-menopausal women to conceive children increases the population growth rate, and some people consider that immoral, too, in a world of finite capacity. The overpopulation argument could well boil down to this: Infertile people do a great service to mankind by not contributing to its number. Nuns, priests, and monks, in choosing to remain celibate, are heroes of the human race. And homosexuals can thank God that they don’t have children. It’s our role as the solution to an overcrowded Earth that just might save us from the fiery furnaces of hell: We do our bit by not reproducing.

No matter that the urge to have children probably can’t be dulled or sharpened by sexual orientation. No matter that if being gay is evolutionarily advantageous and has its basis in genetics, there would, presumably, be no one to carry on the gay gene. Same goes for those selfish, career-minded women over thirty-five who waited too long to have a family: Your barrenness is your path to virtue. An obdurate God is telling you a hard truth. He is saving you from you. (Though perhaps not the Catholic God; God tells Adam and Eve in the Bible to be fruitful and multiply, aside from that Donum Vitae proviso against IVF.)

***

Dr. McDonald wore a lab coat with the Columbia University crown logo on the left and sat behind a desk in her small, cramped office near Columbus Circle. She told me and my partner all about IVF. She had kind eyes, and when she looked at the x-ray pictures of my tubes she called it a “real blockage.”

I was surprisingly fortified by the words, as if they said I was an authentic case, a perfect candidate for IVF, me with my bona fide fallopian snag.

She told me it didn’t matter what caused the blockage — my age, my carelessness — because the treatment is the same. She laughed knowingly when I asked her if IVF would bring on early menopause. “I get that question all the time, but no, it doesn’t,” she said.

“How about quadruplets? Can it bring on those?”

With a colored picture book as her prop, Dr. McDonald explained the IVF process to us. We would begin, she said, by taking hormones to stimulate these little pink circles (my eggs) in these big white circles (my ovaries). When the eggs (usually numbering about ten or twelve) have fully matured (usually on day twelve to fourteen), we would go in with this hollow needle here and suck them out. Then we’d thaw the semen sample and inject this single little tailed circle (sperm) directly into each egg. After twenty-four hours, we would check for these little circles splitting into more circles (cell cleavage), and after about four to five days we’d look for all these little circles (lots of cells). Then we’d implant two of these big circles with all these little circles (embryos) into this uterus and then …

“Then?” I asked. “Well then,” she said, the medical intervention having run its course — Dr. McDonald’s eyes drifting upward, searching for the thing that must happen then, while I waited in anxious suspense for a beautifully luminous, unshakably Western answer. “Then the mother sends a signal to the baby,” she said mystically, and returned my questioning gaze with perfect uncertainty.

***

Scripture contains many accounts of unhappy infertile women, notes the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops on its website. But these stories, it says, ought to give comfort to modern Catholics for whom IVF is out of the question, ending as they almost always do with God answering the prayers of these devotional mothers-in-waiting. There may be “limits to acceptable methods for conceiving a child,” decree these men of the cloth, but, by god, praying isn’t one of them!

The story of Hannah, a barren woman of the Old Testament, goes like this: Hannah is one of two wives of the Levite Elkanah. Elkanah’s other wife, Peninnah, bears their husband children, and she mocks Hannah mercilessly for her infertility. To have children is a blessing by God. To be childless is shameful, a curse. Sorrowful and humiliated, Hannah visits the house of the Lord in the village of Shiloh and prays for a child. She makes a pledge that if he should hear her prayer and give her a son, she would dedicate the boy to him.

The priest, Eli, is impressed with Hannah’s devotion and tells her to go in peace, that her prayer shall be heard. The Lord does remember her, and Hannah bears a boy. She names him Samuel, which means “God has heard” in Hebrew. She fulfills her pledge to give Samuel up to God by handing him over to Eli to be trained in the priesthood.

I can relate to Hannah’s story, her desperation, her plea for the Almighty’s mercy. She isn’t the first biblical woman to be barren, but she is the first to pray to God for help. And if it works for Hannah, and (apparently) my mom, maybe it can work for me. Maybe God doesn’t mean for me to be infertile. Maybe he isn’t trying to tell me something. Maybe I just need to tell him a few things.

***

Photos of babies, lots of babies, can be found in the waiting room of Dr. Yen’s office, on the wall behind the waiting room chairs, on a big cork board. Every inch of the board is covered with baby faces. I see them when I walk in. I catch their shiny foreheads and big eyes. They follow me around the room. Photos of babies and their grateful parents also accompany the many testimonials on Dr. Yen’s website. The site says half of all Dr. Yen’s patients are seeking treatment for infertility.

Acupuncture has its origins in the Taoist concept of dualism, the feminine yin and the masculine yang. This dualism is complementary; yin and yang are co-dependent, part of a universal oneness. Illness or defect in the human body signals an imbalance in the two forces, which blocks the flow of the qi. Acupuncture is said to right the balance and restore the flow by stimulating electrical charges along meridians mapped out by the earliest practitioners. Meridians are the pathways through which my qi flows.

“It not me, it you,” Dr. Yen said, imparting what is surely a Taoist profundity in broken English, as she drove needles in with relish and I cried out in pain. I had a dozen needles in my back, butt, and ankles, but the one over my left kidney, that was the killer. Was that normal, that pitch of pain? Going in, it seared, and I cried out, “Arghhh!” and “No more!” But Dr. Yen just laughed: “Hahaha, don’t worry.”

She was still talking somewhere behind or above me. She hadn’t finished with me yet. Nope, she was going back over her work now, tapping the ends of the embedded needles, giving each of them one last depraved pinnngggg, as if she were conducting an orchestra. “It mean you very blocked. Pain good for you. Don’t worry.” She kept talking like that: “Don’t worry, it you, pain good …” but her strange words started to run into each other like the ocean until the only sound I heard through my agony was white and keening, the wail of a distressed seal.

(At the time I was seeing Dr. Yen I thought her brutality was the only kind of acupuncture there was. I later went to a second, relatively painless acupuncturist, who said Dr. Yen was probably old-school, believing the more a spot hurt, then 1) the more it need acupuncturing, 2) the more the acupuncturing was working, and 3) that 1) and 2) did not contradict each other.)

I started praying the Our Father and the Hail Mary, over and over. I was praying for an end to the torture. But I was also trying Hannah’s trick, praying for a baby.

“Blessed art thou among women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb …”

I pictured my womb. I pictured the empty thing expanding, opening up with the flow of qi from the needles. I didn’t wonder at the ramifications of blending Catholicism with an Eastern religion. I was willing to give myself over to any, every, higher power. I had no choice.

***

Every Thursday morning at Columbia, Nurse Susan teaches IVF class to patients, mostly couples. She wags her forefinger from side to side when explaining something we shouldn’t do or something that mightn’t happen as we would expect.

When my partner and I attended her class, she walked the couples (there were about thirty of us this day) through the different stages of treatment, from mixing and injecting our IVF drugs (it’s do-it-yourself) to undergoing the egg retrieval procedure and embryo implantation. Nurse Susan told us that the meds stimulate the ovaries to produce multiple mature eggs, preferably ten or more, and these are housed in follicles.

“We assume there is one egg per follicle but it doesn’t always work that way,” she said, wagging her finger, as if the capriciousness of our lot were our fault. Egg retrieval, she said, takes place in an operating room and under sedation. The eggs go to the embryology lab to be fertilized by sperm. The fusion of egg and sperm forms a zygote, which splits into two cells twenty-four hours later. The organism is now an embryo. The transfer of embryos three days later also takes place in the operating room, but anesthesia is not necessary. The operating room shares a wall with the embryology lab, and the embryos are passed into the room through a window. The embryologists might decide to use a laser to thin the outer shell of the embryos, to better ready them for implanting in the uterus. Assisted hatching, it’s called, and it’s used for women aged thirty-five and over, whose shells might be thick and hardened with the years.

I beheld with unbidden sincerity the stained glass windows at Saint Francis Xavier Church in Brooklyn, the windows depicting Jesus and the Apostles. I stood in a pew off to the side, where no one could see me. I didn’t pray for a baby, I just recited the Our Father when the priest did and hoped that God read between the lines. I didn’t take communion because I didn’t go to confession beforehand and I remembered from when I was young that this was the proper order of things.

I didn’t go to confession because I wouldn’t have known where to begin confessing and where to end. I hadn’t gone to confession in years; I hadn’t been to church in years. But I wanted to be there, there, in the house of Hannah’s God. The God from my childhood. The God who would surely hear my prayer, no matter that I’d fallen from his grace.

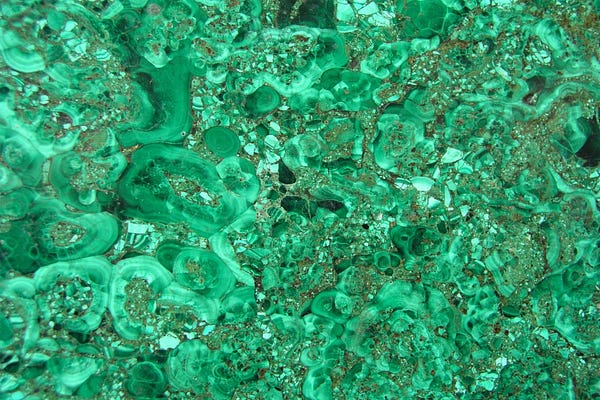

I brought rocks and crystals with me. Yes. I’d been filling my pockets with amulets and taking them everywhere since I found out I was barren, figuring if I once saw the signs of my own infertility in a fortune cookie then I could find the antidote in things equally mystic.

Some of the rocks I’d bought from Angel and Turtle, two dudes who peddled charms at a table at Union Square. There was malachite, a green rock to help ward off negative energy. I was drawn to it immediately, and that was important, everyone at the table agreed. I was taken with hematite too, a black-gray metallic stone known for its balancing, calming properties.

I had other amulets. One was a seashell with a baby seashell lodged inside, a great sign if ever there were one. Another was a turtle with a snake on its back, a fertility-specific charm my partner had found for me.

During mass I held my lucky charms in my hands and imagined the transference of energy back and forth between God and Angel’s stones. I imagined it to be mighty and succoring.

At some point Dr. Yen started to resemble God to me. It happened sometimes when things weren’t going my way, this God-ening of people, of older women, usually. It was bound to happen. I entered the waiting room for a session one week and saw the towering figure sitting there straight-backed, her big right foot over her left knee, a Chinese newspaper in her long outstretched arms. She wasn’t shifting from one room to another, not barking orders like she normally did. She was sitting there like a lowly patient, with a serious reading-face on, as natural as could be. It was like seeing the Buddha sitting at a bus stop.

The informality of the scene I could dig, but the incongruity took me aback, and that’s when it happened: I elevated Dr. Yen so she wasn’t just a doctor trained in the old ways of the East, not merely a gifted woman blessed with healing powers bestowed on her by the gods, she was the First Cause himself, and she would give me a baby like one of those babies on her cork board.

“How are you?” Dr. Yen said, folding her newspaper on her lap as I crossed the threshold, and I couldn’t believe God was addressing little old infertile me.

***

On day two of my menstrual cycle, my partner and I went to Columbia for blood tests, an ultrasound, and a consultation. If all looked good, the consulting nurse said, I could start my first IVF cycle that night, inserting a subcutaneous needle into my stomach and injecting three vials of gonadotropins. The gonadotropins would stimulate my ovaries. After five nights I would add a GnRh-agonist to the drug regimen — a second nightly needle — to prevent premature ovulation. On about day ten I would inject a vial of human chorionic gonadotropin to trigger the release of the eggs from the follicles in my ovaries.

Side effects of the drugs included fatigue, weight gain, mood swings, and something called ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, which in rare circumstances could be fatal. (That usually doesn’t happen to women my age; our sluggish ovaries aren’t likely to be overstimulated.) At each stage of the process, the IVF cycle might be cancelled. If I was not producing follicles, or if the eggs were extracted before they were mature and failed to fertilize, we would stop. Oh, and by the way, I could begin the cycle only if my levels of something called follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) were just so. The blood tests would determine that. I couldn’t fix the levels with drugs. They just changed month to month. It was out of my hands, out of everyone’s hands.

“Are you all right?” Dr. Yen askd, re-entering the room where I’d been lying face down, praying, squeezing my malachite.

“I’m okay,” I said, groaning.

“Hahaha. Don’t worry,” she said. “You leave here feeling taller. Trust me.”

I groaned again. She turned on the light and took the needles out of my back, butt, and ankles. She left to let me dress. I unclenched my jaw and lifted myself up slowly from the table. The relief was immense. There was a feeling, too, of self-satisfaction.

I took a peek inside the plastic bin at the foot of the massage table and saw the long, glistening needles. They were impressively long, weren’t they? And they were poking out of me, weren’t they? I could still feel where they once burrowed deep in my lower back, and it took some time to dress. I hobbled out of the room, hunched over, then out into the street. When the daylight hit my pupils, dilated from the relative brightness of the outdoors, I felt … not like I was floating exactly, but something better, as if I were a ship, a marvelous ocean craft cutting a fearsome passage through the thick, watery crowd on Fifty-Seventh Street. And I did kind of feel taller.

***

The lab would need until five p.m. to process my blood work, the IVF consulting nurse told us. If the blood work was fine, the phone wouldn’t ring. If we did get a call, the doctor would tell me over the phone that I’d have to wait until next month to begin treatment, assuming my FSH had righted itself by then.

We got a call.

It wasn’t Dr. McDonald but another doctor, the one on the roster that day. She told me that this could happen, that it was common for hormone levels to fluctuate, especially as I got older. She offered to answer my questions but I wasn’t able to think of any.

I got off the phone and broke the news to my partner, who asked me what infertility was anyway. Turns out it’s when you can’t start fertility treatment, I joked back.

Well, at least you have your health, or what’s left of it, she quipped. Or how about this one, have you heard this one before …

***********************************************************

Christine Caulfieldis a journalist who frequently covers the law. She founded the journal Lawyerly and has published in Law360. Previous creative nonfiction work has appeared in Passages North.