The future will be seen through plates of glass.

Did Arthur C. Clarke foresee a day when technology would become a replacement for touch and breath and intimacy across Planet Earth?

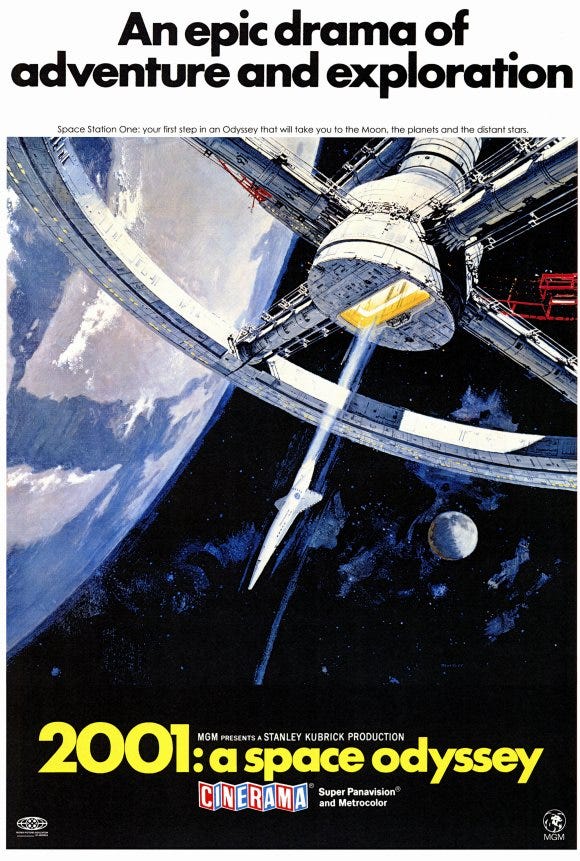

I never wanted to meet HAL or his ghost. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, which came out in 1968, Dr. David Bowman murders the mainframe computer, HAL, when he turns bad actor. But in a kinder technological moment in the film, a space inspector talks with his family through a vivid screen over a great distance.

Arthur C. Clarke, author of the novel, saw today’s FaceTime coming. He knew the good and evil of technology. But did he foresee a day when it would become a replacement for touch and breath and intimacy across Planet Earth?

I didn’t plan on sheltering alone while the Earth rotates. A month ago, in a virtual newspaper, I studied aerial photographs taken by drones and saw that few people roamed our vast metropolises due to Covid-19. If I could have zoomed in close enough, I would have found a whole lot of them hunkered down in their houses, apartments and tents looking at screens. Birthday and wedding celebrations; grandparents meeting little ones for the first time; movies watched synchronously; iPads held up to patients for last rites and last moments with families — all going in and out of connectivity.

There’s a pall over this distance. But I wouldn’t want to be technology-less, with no capacity to see my daughter or search for viral symptoms or order groceries. We’re all aware of the number of people who have lost their jobs and have to find access to a car and enough gas to get to a food pantry line that stretches for miles. On the news, we watch their joy as they load up, before driving back into peril.

When astronauts return to Earth after a prolonged season in space, their bodies feel heavy and dense. I read about this on my phone and think of the first phone I ever used. The receiver like five pounds in my small hands when I talked with my mother. Thanks to my miserable father, I could only see her on weekends. During the week, her voice was far away, nothing like the warmth of being pulled into her skirts. Now I wonder if seeing her on a screen would have done some good or if I would have missed her all the more.

Kubrick explained the end of 2001 in a phone interview. Dave Bowman is taken by God-like entities that place him in something we might call a human zoo in order to study him. He doesn’t leave his little room with its bad décor until he’s on his deathbed. When he’s sent back to Earth, he’s a newborn. More than a few people are out and about now, contracting and spreading the pandemic, curious to see what will happen. Cautious single-dwellers like me might have to wait for the vaccine for a first embrace.

Last year the dirge persisted — the articles on the destructive aspects of young people spending too much time on their computers, online, at a distance. I no longer see those cropping up. Now we turn to almost anyone under twenty-five for their expertise. We want to know how to be virtual and interact through sheets of glass and what it was like to grow up that way. We might even be reborn through them if they give us enough of their secrets.

************************************************************************

Lise Haines’s latest novel, When We Disappear, came out in June 2018. Her previous novels are Girl in the Arena, Small Acts of Sex and Electricity, and In My Sister’s Country, and her short fiction and nonfiction has appeared in journals such as AGNI, Ploughshares, and Cross Currents. Her essay on the adult dating years, “Seek and Hide Again,” was one of our 2019 Pushcart nominees.