A father’s harsh words about a gay son’s suicide echo down the decades. A Broad Street online exclusive.

“Anyone who lives this way deserves to die this way,” he said, looking directly at me …

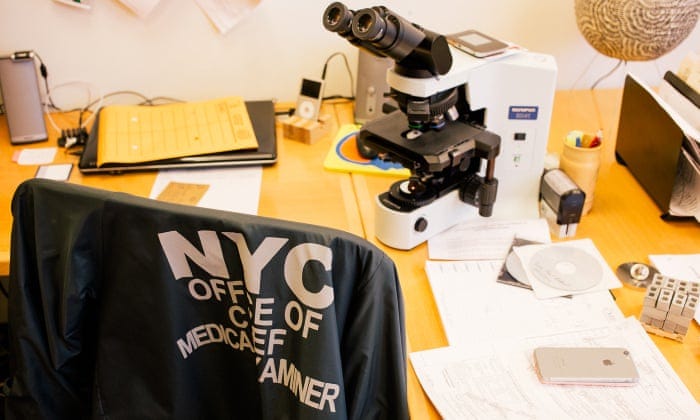

One day in October 1993, I met my parents at the Medical Examiner’s office on 30th Street and First Avenue in Manhattan. A receptionist escorted us into a small waiting room, where my father’s soft-soled shoes squeaked on the linoleum. He paced back and forth while my mother and I sat across from each other in blue plastic chairs. The room was cold.

My father was a big man. And with each lap across the room, it seemed that his body grew larger, expanding into the empty spaces between the three of us.

My mother is thin, as she always has been and probably always will be. She is strong and independent and has taught her children to be aggressive and demanding. In that room, however, she shrank into herself in direct proportion to my father’s expansion. Their grief pushed and pulled between them like a lunar tide.

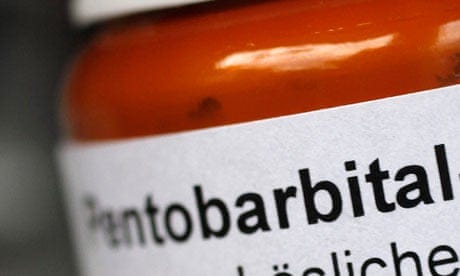

I sat there anticipating the moment when we’d be taken to see the corpse of my brother Mike, who had committed suicide by overdosing on pentobarbital. The only way I could imagine that moment came from T.V. crime dramas: the body covered in a white sheet, the grieving relatives standing next to it, the attendant pulling back the sheet, the moment of revelation, the gasps.

Their grief pushed and pulled between them like a lunar tide.

I was resentful that my parents were with me. I wanted to believe that Mike belonged only to me: two gay brothers comforting each other from having grown up in a conservative religious family. I wanted his death to belong to me, also.

My father’s pacing came from his body’s inability to process emotion, I imagined, as if emotions were a food he couldn’t digest. He’d always been this way. When we were kids, my brothers and I would be arguing around the dinner table about silly things — who broke the chain on one of our bicycles, who cheated at a game of Monopoly — and my father would sit there quietly listening to us until his patience grew thin. Then, his face would tighten and his body would tense up until he couldn’t hold it in any longer. He’d suddenly scream at us to be quiet or bang his fist on the table.

He did this all the time, but each time we were shocked by his anger.

At the morgue, my father’s pacing annoyed me. I wanted to tell him to stop and sit down, but I had never been bold enough to tell him to do anything.

At one point, my father did stop. He came over and stood in front of me. I looked up at him. I felt heat coming off of his body.

“Anyone who lives this way deserves to die this way,” he said, looking directly at me.

I turned away from my father. I would like to say that his condemnation surprised me; I would like to say it made me angry. But I wasn’t surprised, and I wasn’t angry. This was exactly the kind of thing my father would say. At least, the father I knew.

I also felt ashamed, as if I’d somehow been the cause of Mike’s death.

I’ve often wondered if he remembered the words he spoke in the morgue, or if his memory failed along with his body.

Over the years, my brothers and sister have argued with me that my father was too consumed with grief to know what he was saying at the morgue. They question whether he said it at all. They think I have an active imagination that exaggerates the truth. Besides, they assure me, my father loves me as if these secondhand declarations of love are enough to erase memory.

That day, my mother whispered sharply to my father, “Oh, hush, Frank.”

My father returned to his pacing.

I watched him walk to the other side of the room, hoping that he’d walk out the door and leave the identification process to my mother and me. He didn’t.

Soon a tall woman with dark skin came into the room. She wore a blue lab coat and carried a clipboard. My father stopped moving. My mother stood up and steeled herself for this moment. I, too, stood, and I moved toward the door, expecting to be taken to where Mike’s body was being kept.

The woman, however, invited us to sit down. Her voice was calm and soothing. She gave us her condolences, which my mother accepted with a hesitant nod. My father said nothing.

The woman took a Polaroid from her clipboard. The metal clip snapped back in place when she pulled it out. She handed the photo to my mother. I leaned in and looked over her shoulder.

The Polaroid was a close-up of Mike’s face, which was swollen and discolored from lividity. It looked like he’d had an allergic reaction to a bee sting or a spider bite. The swelling was a sickly yellow-green that covered the right side of his face, spreading up and over his nose and lips and eyes.

He was barely recognizable. My mother and I, however, saw the way his hairline arched at its widow’s peak and fell into the soft curve at the center point of his forehead, and we knew that it was Mike.

When my mother handed the Polaroid to my father, who had refused to sit down, he didn’t recognize his son.

“I can’t tell,” he said. “I can’t tell.”

My father held the picture tightly as if he could squeeze Mike’s image out of it.

I wanted to see his body, touch it, maybe. I thought it might make what felt unreal more believable.

“Aren’t we going to see his body?” I asked the medical examiner.

She said that identifying the photo was enough, but I was disappointed. I wanted to see his body, touch it, maybe. I thought it might make what felt unreal more believable.

My mother took the photo from my father and handed it back to the woman, who fastened it beneath the clip.

“It’s him,” my mother said.

*************************************************************************************

When Mike’s body was sent back to Indianapolis for burial, I went to the funeral home there to ask the director if I could see the corpse.

The home was familiar to me. I’d passed it every day when I was a kid on my way to school. Back then, it had looked ordinary: a red brick building with columns at the entrance and tall windows that looked no different from the office building next to it. When I pulled into the parking lot to see Mike, however, it took on a new significance. Somewhere inside the building, my brother’s body lay waiting for us to bury it.

When I walked in the front door, the funeral home was empty. No services were being held; the staff, I assumed, was somewhere behind closed doors getting bodies ready for burial. At the entrance, there was a low desk with a vase of flowers and a stack of business cards. The place smelled of soap, as if the carpets had recently been shampooed.

I waited by the desk for the funeral director. When he came out from the back, I asked to see Mike’s body. He shook his head. He said that the body was in bad condition, but didn’t elaborate.

I didn’t care what Mike’s body looked like. What I imagined was already horrible, decaying flesh and sunken eye sockets, and the sutures on his torso where he’d been opened and emptied and catalogued and put back together. But I didn’t know how to explain to the director that I felt a need to see Mike’s body no matter what. I did not yet have the words to say that if I didn’t see it, grief would find a comfortable place in my body and take up residence as if it were an uninvited guest. Seeing would have given some kind of closure.

Image by pexels.com.

*************************************************************************************

Twenty-three years after Mike’s death, I returned to the medical examiner’s office in Manhattan, where I now live. My shrink had suggested that reading Mike’s autopsy report might help me deal with my grief.

It was enough for my family to know that Mike died, to receive his body, and deposit it in the ground back home in Indiana. They had no need for the particulars of Mike’s death, the gruesome details of the way his body reacted to the poison he consumed. I, on the other hand, cannot let memory go, as if it were capable of resurrecting the dead.

Even while I wished to have had the chance to see Mike’s body in order to say good-bye, I never wanted to dismiss those parts of his life that were grimy and impure and muddled. In the process of remembering him, I want to remember all of him, even if the picture is difficult to look at, and the facts are uncomfortable to deal with.

It felt strange walking into that building again. The memory of the waiting room came back to me instantly, as did my father’s condemnation: “Anyone who lives this way deserves to die this way.”

Requesting the autopsy report was simple. I filled out some paperwork and waited for the report to arrive in the mail.

I expected gruesome details about the way he died, the poison eating away at the lining of his stomach and burning holes in his esophagus.

During the few weeks I had to wait, I imagined what the report would contain. I thought that maybe there’d be a copy of the Polaroid used to identify him. I wondered if there’d be photos of the autopsy itself: Mike’s sternum cracked open and his ribcage pulled apart and his body splayed as if it were part of an anatomy class. I expected gruesome details about the way he died, the poison eating away at the lining of his stomach and burning holes in his esophagus.

When the report arrived, I opened it and sat down in a chair in my bedroom, resting my elbow on a side table in order to lean over and read it under the light from a small lamp.

The autopsy on Mike began at 9:30 a.m. on October 29, 1993, at the hands of Dr. Mark Flomenbaum — a different medical examiner than the one who’d showed us the Polaroid.

Dr. Flomenbaum began by examining the external components of Mike’s body, noting that it was well developed, well nourished and of average frame: 5’10” and 140 lbs.

Mike hadn’t weighed that little since before high school. Perhaps, I thought, he’d lost weight in the months before he died. Or maybe when we die our bodies give up their excesses and leave behind just the bare minimum.

There were a few other inaccuracies in Dr. Flomenbaum’s report. He wrote that the color of Mike’s hair was brown, which might have been the case in the sterile environment of the morgue, where the only light available was from the fluorescent tubes overhead. In natural light, it was easy for me to see that Mike’s hair had the red hues that came from our mother’s Irish ancestry. The doctor noted that Mike had no mustache or beard. He misidentified my brother’s eyes as being gray, rather than the green that became translucent at times and opaque at others. He noted that Mike had natural teeth in good repair. Mike’s torso was hirsute and his genitalia those of a normal circumcised adult male.

To a stranger looking at a body, these observations are nothing more than objective facts. For me, however, the description of Mike’s body reminds me of mine, of the way our bodies became the locus of so much misunderstanding in a family that condemned homosexuality. It was easy to absorb that hate and to internalize that homophobia. To look in the mirror and see that hirsute torso and those perfectly normal genitalia — and feel disgusted. Even today, I avoid looking at my body in the bedroom mirror, afraid that despite the years between his death and now, I can’t escape the past.

In hindsight, it seems to have been so silly to worry about what the body wants when in the end it’s just flesh.

I imagined my brother’s body turning to stone, as if he’d seen Medusa — as if he dared to look into the forbidden, dared to live the kind of life we were taught was anathema to all that was good and right and worthy.

Dr. Flomenbaum noted that rigor mortis was mild in Mike’s body but that “fixed livor was present” at the back, upper arms, face, and neck. It was this lividity that had swollen the face we saw in the Polaroid. The autopsy also noted that “early marbling of the skin is on the shoulders and upper extremities.”

With “marbling,” I imagined my brother’s body turning to stone, as if he’d seen Medusa — as if he dared to look into the forbidden, dared to live the kind of life we were taught was anathema to all that was good and right and worthy. I imagine taking him as a statue and setting him in the garden in my house upstate, where I’d see him whenever I went out to harvest the beans or the peas or the small golden tomatoes that come in quickly and drop to the ground before I have a chance to collect them all.

And then I read, “The extremities are free of needle and track marks.”

This note took me aback. I was offended, the way my mother might have been offended if she’d read the report. (As far as I know, no one in my family has read it, or if they have, they have never spoken of it.) It was as if the M.E. were making a moral judgment about Mike, seeing him as a likely junkie for whom needle and track marks were to be expected. I realized, however, that when the ME received Mike’s body, he must’ve known that Mike died of an overdose. It’d be a necessary part of the autopsy to determine whether the overdose occurred intravenously or orally.

When Dr. Flomenbaum finished his external examination, he began to examine the inside of Mike’s body. He started with the head, which, he declared, had no contusions or fractures or epidural, subdural, or subarachnoid hemorrhages. He measured my brother’s brain at 1580 grams (a little over three pounds), and noted that it was symmetrical, with a normal distribution of cranial nerves. He wrote, also, that “the gray and white matter is normally distributed; the ventricular architecture is unremarkable.”

The idea that Mike’s brain was normal or unremarkable in any way would have offended him. If his sexuality caused him pain, the way my brother’s brain functioned saved him — at least for a little while. He was the smartest one in our family, who attended the best universities and took a job in a Wall Street law firm. As a kid, he’d take I.Q. tests he’d found in magazines just to prove to the rest of us that he was smart. When he came to visit, he’d cite stories in the New York Times when he wanted to prove a point. He’d have known what ventricular architecture was.

As with his brain, Dr. Flomenbaum found Mike’s tongue to be nothing out of the ordinary. But I knew that Mike had a sharp tongue that he used as a weapon. When, for example, we were teenagers living at home and sat down to dinner — our father at the head of the table and Mike just to his left — and when our father would say something egregious that the rest of us knew to ignore — the moral justification for nuclear war, for example — Mike would dive in and befuddle him by citing philosophy and ethics and liberal politics until he was stunned into silence.

From the tongue, and down into the larynx, trachea, and esophagus, there was nothing that concerned Dr. Flomenbaum. When he got into the body cavity, though, the damage that caused Mike’s death began to emerge. The sac around Mike’s heart was filled with 75 ml of a straw-colored fluid. The doctor removed Mike’s lungs and weighed them — the right lung came in at 800 grams, the left at 750 — and noted that “both lungs are markedly congested and contain abundant frothy fluid.”

I’ve found the idea that Mike had to suffer in order to die gives me some perverse pleasure. I want suicide to be painful.

The rest of my family takes comfort in the idea that, while Mike’s suicide was disturbing, he at least died quickly. My mother believes that Mike died from a blow to the head that killed him instantly, as if Mike were the victim of a violent crime. I don’t know where she got this idea, perhaps from someone who was trying to bring her comfort. But I think Mike died violently. I think that after he swallowed the pentobarbital and fell to the floor, landing on his back, he drowned in his own vomit, that alliterative “frothy fluid” that Dr. Flomenbaum described.

I admit, however, that I’ve found the idea that Mike had to suffer in order to die gives me some perverse pleasure. I want suicide to be painful, if not for vengeance’s sake then at least as a deterrent. In those dark moments in my life when I think that death would be easier than living, I want the idea of suicide as pain to stop these thoughts.

Along with the fluid in his lungs, Dr. Flomenbaum noted that there were 60 ml of poisonous bile in Mike’s stomach, although he saw no discernible fragments of pills or tablets, which means that Mike ingested a liquid form of the pentobarbital.

Finally, Dr. Flomenbaum came to his conclusion, writing simply, “Manner of Death: Suicide (Acute Ingestion).”

When I finished reading the report, I replaced it in its envelope and put it in my desk drawer. I turned off the bedroom light and went into the kitchen to prepare dinner. The dogs walked up and pressed their bodies against my legs the way they do when they sense that I need comforting. My husband got up from his desk, came over, and put his hand on my shoulder. He let it rest there as I removed two viscous chicken breasts from their packaging. Then he went back to his desk, and the dogs returned to their spots in the living room.

*************************************************************************************

For a while immediately after Mike died, I visited my hometown a few times a year, stopping by the cemetery to stand above his grave and hope that seeing his name etched in granite would assuage the loss that had anchored itself in my body.

There was, however, a disconnect between Mike’s name on that stone and the body buried beneath. How could there not have been, I thought, when I’d spent most of my life trying to forge a bond between Mike and me that he constantly resisted?

Eventually I stopped going to the cemetery, and likewise stopped visiting my hometown.

My body has transformed into that of my father.

Lately, however, I’ve been going home again, not because I hope to find comfort there — on the contrary, returning to Indianapolis always produces angst — but rather because my father is dying. He has emphysema, and I feel an obligation to see him before he dies. As with standing over Mike’s grave, however, seeing my father’s failing body doesn’t evoke the sympathy I imagine it should. Instead, I feel detached as if, on that day in the mortuary, some vital connection between father and son had been severed and could never be reattached. And I remember —

“Anyone who lives this way deserves to die this way.”

When I was in my twenties, I had the same kind of body as Mike: well developed and well fed and of average height, although I was a few inches taller than he was. My hair was brown but without our mother’s red hues. My eyes were green, as were Mike’s. My teeth were good, although one of my front teeth had been capped after a sporting accident. My body was hirsute and my genitalia were circumcised and normal. My body also experienced sexual desires that the rest of my family found abhorrent.

Now, however, my body has transformed into that of my father. Every time I look in the mirror, I see him reflected back at me: his beer belly and heavy chest, his bald head and thick jowls.

Last winter, I had a series of telephone conversations with my mother. Her voice was heavy and lethargic, when — as with the rest of my family — her normal voice is energetic and a little too loud. My father, she said, was having a bad winter; the cold was getting into his lungs and his body seemed to be unable to generate enough warmth to keep him going. She told me that I should plan a trip home to say good-bye.

When my father was first diagnosed, he and my mother refused the diagnosis, as if the doctors were offering them a choice. They convinced themselves that my father’s phlegmatic coughing was due to allergies or, at worse, a slight touch of asthma. My mother especially rejected the idea that my father was sick; she is strong and healthy, and she believes that illness is the result of a weak mind. However, when he could no longer lie die in bed at night because the compression on his lungs prevented him from breathing, and when throughout the day he had difficulties completing the simplest of tasks — walking from the bedroom to the kitchen, for example — without having to sit down to catch his breath, she reluctantly accepted the doctors’ diagnosis.

Coming home is sign of failure that necessitates a feast.

I arrived in Indianapolis for that farewell visit in early June. As I always did when returning home, I planned to stay for two nights before heading back to New York. By then, my father had survived the winter and was doing much better. When she picked me up at the airport, my mother said that he’d found a physical therapist who was teaching my father how to increase his lung capacity through a series of breathing exercises.

My father looked no different than the last time I’d seen him — his clumsy body no different from mine. He greeted me at the door with enthusiasm, hugging me in the tentative way we’d settled on over the years. We’d been afraid, I think, that in touching each other’s bodies we might bring back memories of Mike and the curse my father laid on Mike and me.

I’d never liked talking to my father, but ever since he became ill, I’ve convinced myself that I should make an effort.

After putting my bag in the bedroom where I used to sleep as a boy, I walked into the dining room, where my father was sitting at his usual place, the head of the table.

Looking at him there, I also had an image of Mike sitting to his left.

My mother was in the kitchen fixing dinner. She’d invited my siblings and their families over to welcome “the prodigal son.”

They use this phrase every time I visit. I cringe when I hear it, as if coming home is sign of failure that necessitates a feast.

“How’s work?” my father asked, as he always asks. He was doing the crossword in the local paper — the Indianapolis Star — and didn’t look up when he spoke, his head down over the paper, his pencil scratching out answers.

“Fine,” I answered, sitting down opposite him, in the seat my mother normally occupied. “How are you feeling?”

“Fine,” he echoed.

He was wearing a yellow polo shirt, beneath which I saw his once-muscular chest drooping like an old woman’s. His arms bore large purple blotches from the bruises he got when any part of his exposed flesh brushed up against any surface. The rest of his skin was thin and translucent, like vellum.

I stared at his hands, which were so familiar to me. He still has the thick hands of a football player; in old photos, he looks tough and intimidating in his uniform. When I was boy, I’d watched him at his workbench in the garage, planing the bottom of a door that stuck or replacing the worn-out handles on a kitchen cabinet.

I looked at my own hands, and as with the rest of my body, they resembled his, although I was never a football player; nor, I hope, did I ever look tough and intimidating. I tried to remember what Mike’s hands looked like, but I’ve lost the details of his body over the decades. I’ve retained only vague memories of what he looked like: a broad nose and thin lips and a medium build. I thought that if it were possible to line us up, we’d represent the different stages of the same man aging over time: Mike the fittest one at the time he died, myself the middle-aged man who hasn’t yet figured out how to accept his body, and my father in the last stages of decline.

Watching my father do the crossword, I noticed how thin his wrists were. I’d never noticed that before. It looked as if beneath the heavy body that I’d always known him to have was a thinner man that I’d never known. My own wrists seemed normal in comparison, except for a very faint scar from a moment in my life when, like Mike, I thought I couldn’t go on.

“Your mother tells me that you’re looking for a new job,” my father said, breaking a long silence.

“Maybe,” I said. I pulled out my phone to check emails, then opened up the Times crossword app to look at the clues I hadn’t figured out for the day’s puzzle.

Yes, we were both doing crossword puzzles — but different ones. It was my way of avoiding talking to him the way he avoided talking to me, even if, perhaps ironically, we used the same means of avoidance.

“Don’t you like where you are?” he asked.

“It’s not that,” I said. “I just want to see what else is out there.”

I looked up from the screen and back at him, this time his scalp. The top of his head was scabby as if he were getting over an infection or had bumped his head on a low-hanging eave or doorway, which he used to do when we were kids.

We’d represent the different stages of the same man aging over time.

In addition to inheriting my father’s body, I’ve developed an anxiety disorder that, looking back, resembles the nervous pacing my father displayed at the morgue in Manhattan. During times of stress, my hands shake and my heart races and the muscles in my leg twitch as if they can’t bear the idea of sitting still.

Stuck in the dining room alone with my father, my body began to quiver. I wanted to think of myself as more mature and less affected by this presence — less haunted by those words he hissed in the morgue back in New York — so I tried to ignore these signs. My body, however, didn’t care that I’d been trying to change, and amplified my anxiety until I felt like jumping up from the table and running around the house like a madman.

I couldn’t tell if my father knew that I was anxious, or if he took pleasure in knowing this, as if my agitated state were a sign that I wasn’t as happy as I pretended to be. Or if he shared my unease and somewhere in his body nervous tics were playing themselves out, despite his best efforts.

I’ve often wondered if he remembered the words he spoke in the morgue, or if his memory failed along with his body.

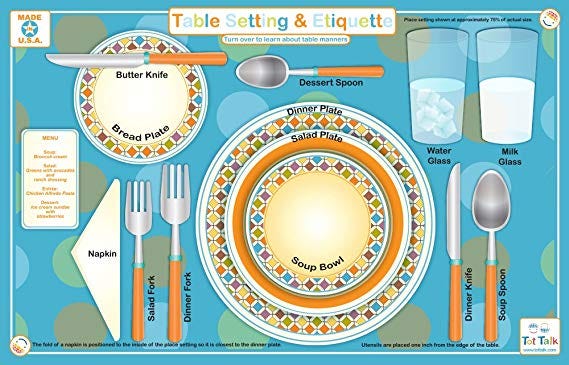

Eventually, my mother came in to set the table for dinner. She put her hand on my shoulder as she collected the everyday placemats in order to set out nicer cloth ones. She understood the tension between my father and me, in the same way she understood the tension that existed between my father and Mike. Over the years, she’s tried to broker a truce between us, but her efforts haven’t been successful.

“Let me help you,” I said, getting up from the table and taking the placemats from her hands.

“I’m fine,” my mother said, trying to take the placemats back from me.

“Let him help,” my father said.

My mother gave up and walked into the kitchen.

I followed her.

*************************************************************************************

My siblings and their families filtered into the house a few hours later. We all chitchatted about unimportant things — the weather, local sports teams, work. They asked me how I was doing and I said that I was fine, that life was moving along, as it tends to do. They agreed. My nieces and nephews hugged me and welcomed me home. I teased them about how old they were getting. They teased me back.

We ate rapidly, as we always did, and then retired into the living room, where they watched football while I flipped through an old copy of Newsweek. When the game was over, my siblings trickled out of the house and left my parents and me alone.

“I’m off to bed,” my father said eventually. He struggled to get up out of his chair, then shuffled across the living room. “I’ll see you in the morning, young man.”

“He means well,” my mother said when he he’d gone down the hall to their bedroom. She sipped tea from an old mug.

“I know,” I said.

I wanted to believe that my father held no animus toward me, and perhaps he didn’t.Perhaps the words he said in the morgue were simply words of grief and not condemnation. Perhaps, I told myself, it was time to forgive him.

I got up from the sofa, wished my mother good night, and went upstairs to my old room. I had a tough time sleeping, though. There were too many memories in that bedroom to leave me in peace: the nights I prayed endlessly to be a normal boy, the night I swallowed a half-dozen sleeping pills when I knew that my sexual difference was something I couldn’t set aside, the nights I wished my father dead so that I could live unencumbered by his moral dictates.

In the morning, when I walked out the bedroom door, I heard my father’s voice calling me from the room next to mine. I went into the room, which my father had converted into an office — my father is an accountant who’s had his own practice for decades and, refusing to retire, still has a few clients. In the middle of the room stood a large desk with a credenza, and in front of the desk stood two chairs for clients to sit in. I sat in one of the client chairs while he sat behind his desk.

I wanted to believe that my father held no animus toward me, and perhaps he didn’t…. Perhaps, I told myself, it was time to forgive him.

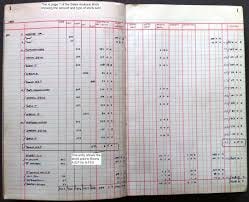

In front of him a ledger book lay open. To the right were a calculator and a blue mechanical pencil; he liked that kind because the lead had a sharp edge and produced the kind of crisp numbers he liked. There were other ledger books stacked on the credenza next to his computer.

“Do you know what this is?” he asked, pointing to the open ledger book. I shook my head. “Records of a client who owns a number of Subway franchises. You can’t imagine how much money he makes.”

For a half an hour, I sat in my father’s office while he chatted about his clients and their financial successes. I was tired and cranky from not having slept, and couldn’t figure out what he was talking about or why. He couldn’t have believed that I cared at all for his clients or his accounting practice. He couldn’t have been that obtuse. But then I realized that he was talking to keep me there as long as he could. He knew that I was quick to make excuses to get away from him, and his small talk was a way to keep me a little while longer. I also realized that, to my father, this banal conversation constituted affection. This was the most I’d ever get from him.

I thought that if I were a good son, I’d take whatever affection my father was willing to give and excuse the rest. But I also saw myself as a brother with a duty to protect the memory of a sibling who was lowered into the ground with the curse of his father on his head. I couldn’t reconcile these two demands the way an accountant might have done. I still can’t.

I felt cruel; I thought maybe my presence was torture to him, and at that moment I didn’t mind torturing him.

At one point in his chatter, my father paused. He’d run out of breath and needed to do one of the exercises his physical therapist had taught him. He closed his eyes and took in a steady breath, held it for a moment, and then let it out.

In that pause, I could’ve made my escape, or I could’ve broached the subject of Mike’s death, but I didn’t do either of these things. Instead, I leaned back in my chair and waited until he’d caught his breath. I felt cruel doing nothing; I thought maybe my presence was torture to him, and at that moment I didn’t mind torturing him. At that moment, I should’ve been kind, but I chose not to be. I should have forgiven him but I chose not to forgive. I could have loved him but I chose not to.

When my father finished his breathing exercises, he opened his eyes and stared at me.

He said, “You’re getting fat. You’d better watch yourself.”

I patted my belly and laughed despite myself, saying, “Look who’s talking.”

“I’m just telling you the truth,” he said, as if we’d always spoken the truth to each other.

*************************************************************************************

Andrew (A. W.) Barnes’s book of essays, The Dark Eclipse: Reflections on Suicide and Absence,debuts with Bucknell University Press on December 14, 2018.

The publisher describes the book as“personal essays in which A. W. Barnes seeks to come to terms with the suicide of his older brother Mike. Using source documentation — police report, autopsy, suicide note, and death certificate — the essays explore Barnes’s relationship with Mike and their status as gay brothers raised in a large conservative family in the Midwest. In addition, the narrative traces the brothers’ difficult relationship with their father, a man who once studied to be a Trappist monk before marrying and fathering eight children. Because of their shared sexual orientation, Andrew hoped he and Mike would be close, but their relationship was as fraught as the author’s relationship with his other brothers and father. While the rest of the family seems to have forgotten about Mike, who died in 1993, Barnes has not been able to let him go. This book is his attempt to do so.”

Andrew holds degrees in accounting, creative writing, and English literature. Noting that his original area of study was “Early Modern English Literature with a speciality in seventeenth-century poetry and gender theory,” he has recently devoted himself to creative nonfiction, publishing work in Sheepshead Review andIf and Only If. He is dean of the School of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Pratt Institute.

Be sure to read our interview with Andrew, in which he discusses truth, memory, the writing process, and his current relationships with siblings and parents.

This feature is also available, in slightly different format, on Medium.