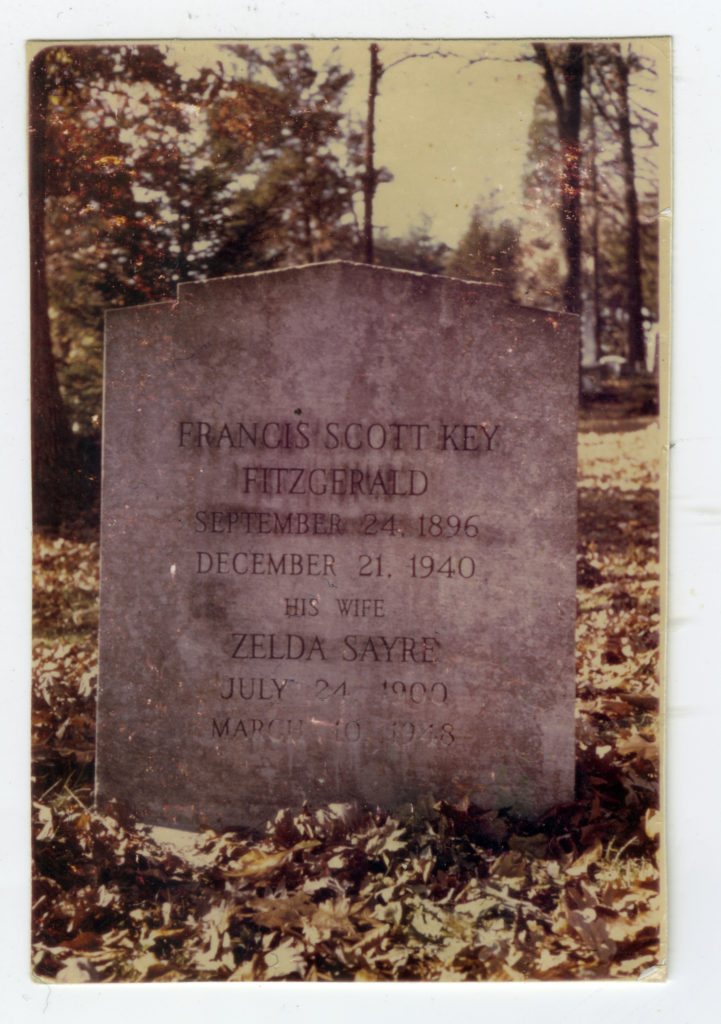

In 1970, three avid young Fitzgerald scholars took a joy ride in search of Scott and Zelda’s first resting-place. One result is the only known published photo of that original gravesite, which appeared first in Broad Street‘s “Maps & Legends” issue …

Finally Rick struck a match by a gravestone and yelled, “They’re here!” … Things went glimmering.

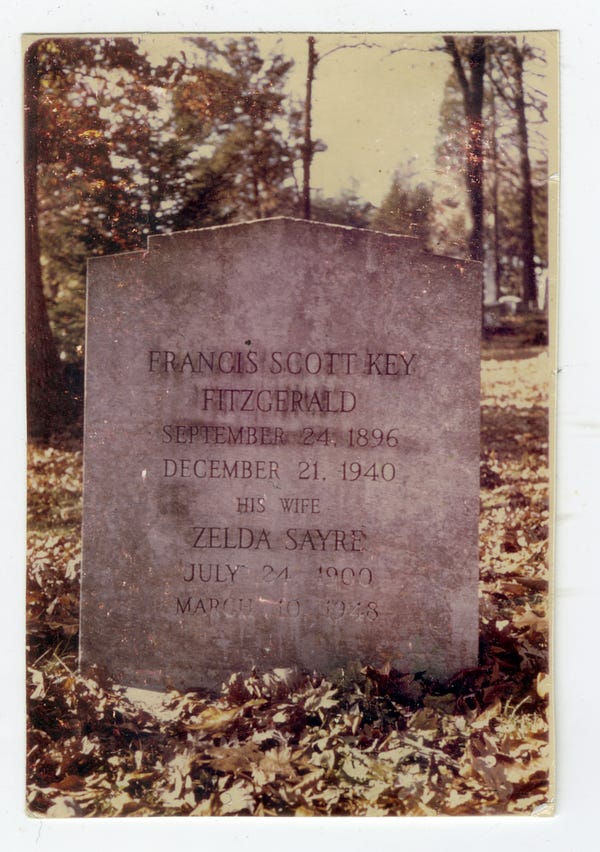

This photograph of the Fitzgeralds’ first resting-place was taken by Richard Anderson in 1970 when he, James West, and Bryant Mangum–author of this essay–went to find Scott and Zelda.

It is the only such photograph known to exist and to be available to the public.

Photos of the current gravesite and the full story of that trip are featured below.

You can click here to read the full article on Medium, or simply read onward with us here …

***********************************************************************************

“An Affair of Youth”

By Bryant Mangum

*********

Editors’ Note

One unseasonably warm autumn night in 1970, three young scholars took a martini-fueled joyride to tour the cemeteries of Rockville, Maryland. They’d decided they needed to visit the final resting place of their beloved author, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and his wife, Zelda–they had some questions that only a gravesite could answer.

James West, Richard Anderson, and Bryant Mangum had come to the South Atlantic Modern Language Association’s annual meeting (SAMLA) in Washington, D.C., in search of teaching jobs to take when their Ph.D.’s were at last conferred. Richard and Bryant were South Carolina natives and James was a Virginia gent, all three having found roundabout ways to get to graduate school in the late 1960s at the University of South Carolina in English — and also, as it turned out, into the first seminar on Fitzgerald taught by Matthew J. Bruccoli, who had just then begun research on what would become his acclaimed biography of Fitzgerald: Some Sort of Epic Grandeur.

The events of that night would become legendary themselves.

******************************************************************************

“I wouldn’t mind a bit if in a few years Zelda + I could snuggle up together under a stone in some old graveyard here [Baltimore, Maryland]. That is really a happy thought + not melancholy at all.”

— F. Scott Fitzgerald (letter to Laura Guthrie, 23 September 1935)

The three of us sat with our not-so-encouraging job interviews behind us in a not-so-promising job market, with nowhere especially to go before the SAMLA meeting officially ended except into rooms of panel discussions on subjects that looked from the listings of titles in the conference program to be, frankly, boring. Certainly none of them were on Fitzgerald. Of course, we could just head back to Columbia to work on our dissertations …

Instead, in honor of the couple we had read and read about so diligently, not to mention worked so hard to understand, Rick ordered a round of martinis made to his exact prescription, which was his own jazzy riff on the gin rickey, a gin-and-lime-juice concoction that had reportedly been Fitzgerald’s favorite cocktail: four ounces of Bombay clear-bottle, 86-proof gin to one ounce of Martini & Rossi extra-dry vermouth, lightly shaken so as not to bruise the gin, slightly dirty, with two olives; and, with apologies to Fitzgerald, definitely no lime juice.

Our martinis in hand — and glad to be out of our seersucker suits and in our Lacoste Crocodile shirts, khakis, and Bass Weejuns without socks — we raised glasses in a toast to Scott and Zelda.

A few sips into our first round, someone — I can’t remember which one of us — suggested that we go and find the Fitzgeralds. We knew they were buried somewhere near Rockville, Maryland, and that could not be far, we reasoned, from Washington, D.C. Some more sips later, we decided together to go out in search of them. A pilgrimage to their grave would be a proper ending to the conference, we all agreed — more than proper, in fact, after a second round of martinis.

This unanimity was not predictable, since although Rick, Jim, and I had worked side-by-side for years now doing research on Fitzgerald, we had worked separately, each in his own area of research; and I’m not certain that any of us could have named the specific research interest of the others.

We had, after all, first been thrown together by the mere circumstance that each of us had developed as undergraduates some compelling, if hazily defined, fascination with a facet of the work or life of F. Scott Fitzgerald:

F. Scott Fitzgerald poses for a portrait in the 1920s.

a facet that each had chosen to nurture for the most part privately. It was that circumstance that had brought us together in Bruccoli’s first seminar along with thirteen other graduate students — all of whom had immediately dropped the course after the first class, in which Professor Bruccoli (wearing a three-piece gray herringbone suit from Brooks Brothers and sporting a buzz cut and fuzzy-worm mustache) announced that anyone who didn’t want to spend fifteen hours a day, seven days a week, doing research on F. Scott Fitzgerald for the next four months should “get the hell out of the room.”

Jim, Rick, and I had, in poker parlance, stood pat — pals at the moment, pals united in the prospect of tireless research work, pals joined forever as Bruccoli’s first three Ph.D.’s-to-be. Pals now in this D.C. endeavor, dedicated to finding Scott and Zelda’s grave without knowing what, if anything, we expected to discover there that we had not already uncovered in our research.

Perhaps, I’ve concluded in retrospect, we were going to the Fitzgeralds’ grave hoping to get a push that would move us closer to final answers. As researchers finishing our dissertations, all three of us had lingering questions — big questions and small ones — that I am certain we all wanted to ask Fitzgerald at his graveside. For me, among the biggest ones were these: How did you find the magic elixir that rendered The Great Gatsby, in T. S. Eliot’s words, “the first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James”? Why do we beat on, boats against the current, even as we are borne back ceaselessly into the past? Could Gatsby have “turned out all right in the end” if he had not been killed by Wilson? How did you manage to sprinkle the brutally callous Judy Jones of “Winter Dreams” with stardust? Why did you use an ampersand in the title “Dice, Brassknuckles & Guitar?”

We all had our own lists of questions, I am sure, and I suspect on some level we imagined that we might get answers to or nudges toward them when we at last reached the gravesite. The three of us, after all, had long ago concluded what Fitzgerald’s daughter, Scottie, would write in a 1974 Family Circle article about her father, several years after our pilgrimage: “In his way he was a prophet.” Would he not prophesy for us from the grave?

After consulting with the bartender as to the approximate distance to Rockville, Maryland, we predicted it would be a half-hour drive. We piled into my appropriately solemn long black four-door Impala and began the journey.

*********************************

“I suppose that poetry is a Northern man’s dream of the South.”

— “The Last of the Belles” (1929)

We were all Southerners, Jim, Rick, and I, with considerable pride of region as well as some personal knowledge of the Zelda-like belles of the New South; and each of us, no doubt, had remained curious about the process by which Fitzgerald, a Minnesotan, had come to understand the South so well. A question, perhaps, for Zelda?

Jim had come from Blacksburg, Virginia, through Randolph-Macon College, and had brought from his father’s side a genteel Tidewater Virginia accent that led him regularly to use prepositions like “aboot” (“about”) and nouns like “hoose” (“house”).

Rick was from the up-country, a village just outside Spartanburg, South Carolina, called Tucapau, and held an undergraduate degree from Washington and Lee and an M.A. from the University of Virginia. After UVA, he’d done time in the army, picking up while in Germany a liking for fine pipe tobacco with heavy hints of Latakia, which by outward signs he enjoyed beyond words as he sat puffing away behind his T.A. desk in the Humanities Office Building on the University of South Carolina campus.

I had come to the Gamecock-red Carolina university in the summer of 1968 by way of the Tar Heel-blue one in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. I had defected from a childhood and adolescence in the South Carolina low country between Charleston and Savannah — a few miles south of Pocotaligo and Coosawhatchie — and then high school years in Darlington, where I had learned from peers painful lessons about, among other things, my way of speaking. I learned, for instance, that I should never order a “bayuh” (“beer”) or talk of people who go “dayuh huntin’” (“deer hunting”) if I hoped to be understood and appreciated by Darlingtonians, all of whom spoke “proper” English, unlike the friends, teachers, and Little League coaches of my youth — and myself. That accent, incidentally, has never entirely left me. By 1972, when I began my teaching career at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond — a city that my Darlington friends thought to be “in the North” — I assumed that I had lost all traces of any regional accent. Then one day in Hibbs Hall during my first year at VCU, the dean stopped me to say he had spoken with an exchange student from India — schooled recently in London — who told him that she was very much enjoying my American literature class, but that she was curious as to what language I was speaking.

But vernacular aside for the moment, and returning to the circumstances that were uniting the three of us in our desire to search for Scott and Zelda’s grave: Our unanimity in this venture was not predictable. Back on campus, none of us had discussed our research in much detail, as is typical of graduate students. I vaguely remember that when we were dividing up topics for further exploration, Jim had expressed special interest in This Side of Paradise(1920), which at the time would not have been my first choice for focused research; Rick, I recall, had said something early on about a particular fascination he had with Zelda’s paintings and also about Maxwell Perkins as Fitzgerald’s editor at Scribner’s. For my part, in Chapel Hill I had fallen in love with girls of the short stories: Judy Jones from “Winter Dreams” (December 1922) and then Sally Carrol Happer in “The Ice Palace” (May 1920) — but I had kept my feelings mostly to myself since Judy seemed almost universally disliked for breaking Dexter Green’s heart, and many considered Sally Carrol suspect because of what they believed to be her bogus, New South championing of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. So rather than mention Judy or Sally Carrol right off, I simply expressed a general liking for Fitzgerald’s short stories, sharing with strangers only in a vague way my feelings about reasons for my particular interest.

Jim, Rick, and I had more often than not snapped at each other over who would next use the Hinman collator to compare various printings of a Fitzgerald first edition, or who would handle on that particular day the Fitzgeralds’ scrapbooks, with which we had been entrusted by their daughter, Scottie, or who would have the box of letters between Fitzgerald and his literary agent, Harold Ober, to carry out our assigned transcriptions, or who would trek over to place an order for reference materials with Miss Mary E. Goolsby, the interlibrary-loan librarian. In retrospect it seems a bit puzzling that we had not typically been engaged during our graduate years in debating the fine points of Fitzgerald’s fiction or the joys and heartbreaks of Scott and Zelda’s life together. But we had not. We had been occupied with our work.

My own work ended up centering on Fitzgerald’s search for heroes and heroines who manage to reconcile the new existential quest of the modern age with the genteel chivalric tradition. The flapper creed was most closely allied in Fitzgerald’s mind with the existential quest, while the code of the traditional Southern belle, on the other hand, was grounded in the chivalric ideal.

A flapper from the Gazette du Bon Ton, c. 1921.

Fitzgerald most clearly confronted these conflicting codes in his Southern narratives — that is, as a Northern man with his dream of the South — in what has come to be known as his “Tarleton Trilogy”: “The Ice Palace,” “The Jelly-Bean” (October 1920), and “The Last of the Belles” (March 1929). These three Southern-set stories dealing with the flapper and the Southern belle were all popular-magazine pieces that earned high prices for their writer; all three grew out of Fitzgerald’s relationship with Zelda and her South; and all three, it was clear to me from the beginning, are among Fitzgerald’s finest. Artistically they work largely because of the carefully balanced tension that Fitzgerald identifies in the opposition the stories present between a value system founded on romantic ideals — as is the Southern belle’s in its attachment to the chivalric notion of noblesse oblige — and the flapper’s pragmatic philosophy of gratifying the senses since all gods are dead and all faiths in man are shaken, the human condition after World War I as seen by Amory Blaine near the end of This Side of Paradise.

Over the years that have followed our graveyard trip, I have found that the Tarleton stories provide a useful lens through which one can view the progression of Fitzgerald’s ideas about the plight of the hero — and his heroine — in modern times.

**************************************

“ ’At’s all life is. Just going round kissing people.”

— “Head and Shoulders” (1920)

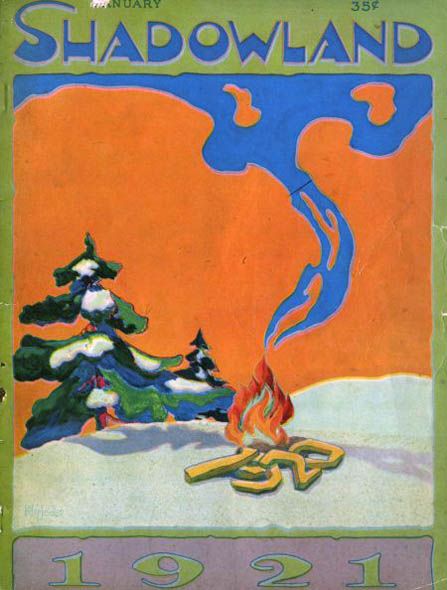

In January 1921, barely a year into the Jazz Age and at the beginning of only his second year as a professional writer, Fitzgerald made this comment about his fictional heroines in a Shadowland interview prophetically titled “Fitzgerald, Flappers and Fame”: “[W]e find the young woman of 1920 flirting, kissing, viewing life lightly, saying damn without a blush, playing along the danger line in an immature way…. Personally I prefer this sort of girl. Indeed, I married the heroine of my stories. I would not be interested in any other sort of woman.”

In his first story to appear in the Saturday Evening Post,“Head and Shoulders” (21 February 1920), he introduced a heroine, Marcia Meadow, who was “this sort of girl” and was based loosely on Zelda — likely the first fictional flapper to appear in a mass-circulation American magazine. Marcia reveals the essence of the flapper code with this one line spoken to her soon-to-be husband, Horace Tarbox, a Yale graduate student in philosophy: “’At’s all life is. Just going round kissing people.”

The story of Marcia and Horace was just the beginning of the complex and many-faceted story of Fitzgerald, who was soon to become the poet laureate of the Jazz Age. He went on to write more than 170 short stories, many of them bringing into American popular culture a hybrid fictional creation of the flapper and the Southern belle, countless essays and book reviews, and five novels.

The “Tarleton Trilogy” stories, as I’ve noted, are among his finest works, in large part because of the balance between the Southern belle’s romantic ideals and the flapper’s pragmatic hedonism.

********************

“But, by God + Lorimer [Saturday Evening Post editor], I’m going to make a fortune yet.”

— Letter to Harold Ober, 5 February 1922

Through time, Fitzgerald himself developed three identities. The first, the one who would have been known to popular readers in his day, was the historian-in-fiction of Jazz Age youth culture who wrote short stories for the widest-reaching magazines and who was known to millions of middle-brow readers as an expert on flappers and young love — a writer who wrote mainly for money and made a lot of it, which he promptly squandered.

A second Scott Fitzgerald was often featured in gossip columns of the early 20s as one half of the couple of Scott and Zelda — shebeing one of the first flappers and the one who openly inspired Fitzgerald’s merger of the flapper and the Southern belle — and theytogether standing as emblems of the Jazz Age until the time of the stock market crash of 1929, after which Scott wrote of their lives with what he called “the authority of failure” — a failure that resulted from his descent into alcoholism and Zelda’s into mental illness.

The Fitzgerald that is largely a construction of popular culture — the Fitzgerald that some know now only through the Baz Luhrmann version of The Great Gatsby — has tended to blur the truth that he was above all a serious literary artist. This third Fitzgerald, probably known better to us now than he was to readers of his time, was the creator of a handful of the finest American stories, short and long, such as “Babylon Revisited,” “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” and The Great Gatsby. This is the Fitzgerald who wrote primarily from love for his art and who, from the very beginning of his career and even in his most commercial magazine fiction, was in search of heroes and heroines who would manage to reconcile the new existential quest of the modern age with the genteel chivalric tradition.

As a professional author and literary artist, that first Fitzgerald I described learned quickly that to earn a living from his writing he had to produce popular stories for slick magazines like The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Metropolitan, Redbook, and Hearst’s International — magazines with circulations in the millions. They paid prices ranging from a few hundred dollars to $4,000 or more per story (about $50,000 in 2015 values). As his correspondence with his literary agent, Harold Ober, indicates, early in his career Fitzgerald received numerous rejections from magazines that paid well; and after giving away his finest efforts to high-brow publications like The Smart Setfor $35 or $40 each, he began to realize he had to tailor his work to the tastes of middle-brow or mainstream readers — a realization that likely prompted him to write that first story about Marcia and Horace, which was his first commercial success and for which he was paid $400 (the equivalent of $5,000 in 2015).

And so it was that Marcia Meadow became his first fictional flapper and “’At’s all life is, just goin’ around kissing people” came into American popular culture as a part of the flapper credo.

Fueled by that success, Fitzgerald began writing more flapper stories, and they were bought quickly by the Post, which published six of them in 1920. By the end of 1924, Metropolitan, Hearst’s International, Liberty, McCall’s, and Collier’s had each published at least one Fitzgerald story — Metropolitan had published four — and in several cases these magazines had paid higher prices per story than the Post. The 1920 Post stories earned increasingly high prices, up to $900 each by the end of 1920, and $1500 each by 1921 — stories such as “Myra Meets His Family” (20 March 1920), “The Camel’s Back” (24 April 1920), “Bernice Bobs Her Hair” (1 May 1920), and “The Offshore Pirate” (29 May 1920).

Like many of these flapper stories, his first novel, This Side of Paradise, appeared in 1920. In the 1921 Shadowland interview, Paradise was already characterized as “his now famous flapper tale,” though none of the females in the novel, with the possible exception of Eleanor Savage, approach the independence of the flappers of his early short stories. Clearly Fitzgerald understood the kind of “pattern” stories about young love with their familiar flapper heroines that the highest paying magazines came to want and expect from him; and he was able, at least through the mid-1920s, to deliver the stories that had become synonymous with his “brand” — more than a dozen of them “flapper” stories. That well eventually ran dry; by the mid-1930s he had to admit to Ober that when he tried to write pattern stories with flapper-like main female characters “the pen just goes dead on me.”

********************

“I had no idea of originating an American flapper when I first began to write. I simply took girls whom I knew very well and, because they interested me as unique beings, I used them for my heroines.”

— Interview with B. F. Wilson, 1923

With that beginning in 1920, Fitzgerald’s flappers gained status as cultural icons who were strong, free-spirited females of the post-World War I period, described in Frederick Lewis Allen’s Only Yesterday (1931), an informal history of the 1920s,in this way: “The flappers wore thin dresses, short-sleeved and occasionally (in the evening) sleeveless; some of the wilder young things rolled their stockings below their knees, revealing to the shocked eyes of virtue a fleeting glance of shin-bones and knee-cap; and many of them were visibly using cosmetics.” These “young things” were often associated in magazine illustrations of the time with flapping galoshes and bobbed hair.

Zelda was often featured in magazines as a perfect example of a flapper.

The origins of this girl’s name go back to 1918 England, where the word “flapper” referred to a young girl who had not yet been introduced into society. The description was slightly modified by John O’Hara in “Mrs. Stratton of Oak Knoll” as British slang referring to “a society girl who had made her debut and hadn’t found a husband.” She would go on to become a fixture in film, with Colleen Moore and Clara Bow as early movie flappers in such movies as Moore’s The Perfect Flapper (1924) and Bow’s It (1927), the silent movie that established her as the “the It Girl” — “it” referring to sex appeal.

But the American flapper as a fictional type fit for print was truly Fitzgerald’s invention. After the Jazz Age was over, Fitzgerald wrote in an essay that he was shocked, after the publication of “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” to find his mailbox filled with literally hundreds of letters from females all over America asking how they could become flappers and where they should go to get their hair bobbed. “I had no idea of originating an American flapper when I first began to write,” he said in a 1923 interview. “I simply took girls whom I knew very well and, because they interested me as unique beings, I used them for my heroines.”

********************

“Darling Heart, our fairy tale is almost ended, and we’re going to marry and live happily ever afterward.”

— Zelda Sayre (letter, 1919)

The “girl” that Fitzgerald knew best was Zelda, the “heroine” he married in 1920 — the one who was thought of and is remembered as one half of the couple of Scott and Zelda and without question the most important model for Fitzgerald’s early fictional women. Zelda Sayre of Montgomery, Alabama, was described in a popular magazine of the 1920s as “that living prototype of that species of femininity known as the American flapper,” and she deserves credit not only for her role in furthering the flapper movement in America but also for providing Fitzgerald with a model for creating in fiction his hybrid type of the flapper and the Southern belle.

Scott and Zelda met at a country club dance in 1918, when he was in the army and stationed outside Montgomery. He was on the rebound after his rejection by his first love, Ginevra King, a debutante from Lake Forest, Illinois (a posh exurb on the shore of Lake Michigan, about thirty miles north of Chicago). He and Ginevra had met in January 1915 while he was a student at Princeton; he wrote in a 1937 letter to Scottie that she had thrown him over with “the most supreme boredom and indifference.” However, from the moment Scott met Zelda, shebecame the love of his life, and she both furnished him with a model for most of his fictional heroines and gave him incentive to become financially successful as a writer. As he put it in his 1937 essay “Early Success,” he had fallen “in love with a whirlwind and I must spin a net big enough to catch it out of my head.”

For starters, he gained from Zelda the material that during their courtship he spun into the net of the first story in his Southern narrative series, “The Ice Palace.” But it was only after he was able to report to her that This Side of Paradise had been accepted by Scribner’s and that the Post had accepted “Head and Shoulders” that she agreed to come to New York and marry him. When he gave her news of his acceptances, she wrote to him, “Darling Heart, our fairy tale is almost ended, and we’re going to marry and live happily ever afterward.” She came immediately to New York, and by the time of their marriage in April 1920, in the rectory of St. Patrick’s cathedral, the legend of Scott and Zelda had begun.

Due in no small part to his association with Zelda, the quintessential flapper and the one who had given him much of the material he had thus far written about, Fitzgerald was elevated to the role of official flapper’s historian.

The public media depicted the Fitzgeralds as the glittering, perfect couple of the Jazz Age; their every move was reported in gossip columns and embellished by rumor, including such activities as riding on top of taxicabs through New York City and dancing fully clothed in the Pulitzer fountain in front of the Plaza Hotel.

Meanwhile, both Fitzgeralds themselves were publishing article after article on flappers in popular magazines, many of them clipped from magazines and newspapers and pasted in their scrapbooks. In one of the last of these, “Eulogy on the Flapper” (1922), Zelda ominously pronounced the flapper “deceased”: her days were always numbered, Zelda believed, though her youth had given her for a time “the right to experiment with herself as a transient poignant figure who will be dead tomorrow” — dead because she will be, in the words of Eleanor in This Side of Paradise (very likely, in reality, the voice of Zelda) “tied to the sinking ship of future matrimony.” Zelda knew that her own future had already been tied to this sinking ship, but that the young, unattached single woman — the flapper archetype — would exercise her right to live free of social inhibitions and with “unadulterated gaiety” well into the 1920s and beyond.

********************

“Novelist Says Southern Type of Flapper Best”

— Newspaper article subheading, c. 1922

Through Zelda, Fitzgerald became familiar with a flapper who also fit an older and sometimes opposite model of femininity, the Southern belle. One of Fitzgerald’s dilemmas in — and solutions to — resolving the conflicts within his character types is presented graphically in an unattributed newspaper article pasted in the couple’s scrapbooks: the author is shown standing in front of a map of the United States, declaring that flappers can be found everywhere in America but that he “Likes Southern Type of Flapper Best.”

Zelda was a belle of the New South, a kind of girl described most memorably in “The Last of the Belles”: “There [Ailie Calhoun] was — the Southern type in all its purity…. She had the adroitness sugar-coated with sweet, voluble simplicity, the suggested background of devoted fathers, brothers and admirers stretching back into the South’s heroic age, the unfailing coolness acquired in the endless struggle with the heat.”

As both flapper and belle, Zelda forced Scott to work through the binary oppositions in his personal relationship with her and in his early fictional heroines, especially to the degree that he was drawing on and from Zelda as his model and as a major source of his material for his fiction. There can be little question that he did draw both on and from Zelda, as she indicated in her New York Tribune review of his second novel, The Beautiful and Damned (1922): “Mr. Fitzgerald seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home,” she wrote with reference to lines from her diary that appeared in his novel.

“The Circus,” a painting by Zelda.

****************************

“When I write about the south, I write about it as I saw it in Alabama. I chose the name of Tarleton, Ga., because I know Georgia and Alabama towns are pretty much the same.”

— Interview, 1923

The two stories that best demonstrate Fitzgerald’s treatment of the flapper who is also a Southern belle are “The Ice Palace” and “The Jelly-Bean,” both of them set in Tarleton, Georgia, and both owing much to Fitzgerald’s relationship to Zelda.

In “The Ice Palace” Sally Carrol Happer is the Southern belle/flapper who takes her Northern fiancé to a Southern graveyard and waxes eloquent about her belief in the chivalric code: “people have these dreams they fasten onto things, and I’ve always grown up with [my] dream…. I’ve tried in a way to live up to those past standards [of the dead Old South] of noblesse oblige — there’s just the last remnants of it, you know….” But Sally Carrol also admits to one of the local boys, Clark Darrow, that “There’s two sides to me, you see. There’s the sleepy old side you love; and there’s a sort of energy — the feelin’ that makes me do wild things. That’s the part of me that may be useful somewhere, that’ll last when I’m not beautiful any more.” And though Sally Carrol tries to explore the “flapper” side of herself that wants to “go places,” wants “to live where things happen on a big scale,” she finally rejects that outside world and embraces her dual identity of flapper and belle in the place that she considers home: the South.

So the flapper creed is allied with the existential quest; and, as is best illustrated in “The Jelly-Bean,” when that creed is not tempered with the backward glance or with the hope for a future in which ideals and the imagination survive, its days, to Fitzgerald, are numbered. Its practitioners will wind up, heaven help them, married and living out their days in Savannah, a Southern city that Fitzgerald inexplicably characterizes in at least two of the stories as a kind of purgatory that has no regional identity.

In “The Jelly-Bean,” flapper Nancy Lamar is only coincidentally a Southern belle. Here is what she tells Jim Powell, the eponymous jelly-bean, who is defined in the story as a corner loafer “who spends his life conjugating the verb to idle in the first person singular”: “I’m a wild part of the world, Jelly-Bean…. I’m not like any girl you ever saw.” Nancy winds up later in the evening getting married, while drunk, to the son of a razor manufacturer from Savannah — obviously, with no apparent allegiance to the Old South — more flapper than belle.

Based on these two stories, it is an arguable point whether the Southern belle is destined more than the flapper to be a casualty of a society that situates woman on a pedestal, a society that is at heart patriarchal. Fitzgerald seems to argue in his final flapper/belle story, “The Last of the Belles,” that the belle is more vulnerable. When Andy, Fitzgerald’s narrator/persona, returns to the South, he discovers that the image of the girl he thought had been of the love of his life, Ailie Calhoun, was founded on illusion — that Ailie’s Southern belle was in fact what C. Hugh Holman, eminent Southern literature scholar, has called “wistful nostalgia made flesh” — in effect, a construction of the male imagination. As Ailie prepares to leave Tarleton to marry the man from Savannah, Andy writes, “the South [will] be empty for me forever.”

In fact, the South never became empty for Scott or for Zelda. Scott continued long after the Jazz Age had ended to explore in his fiction (in the 1933 story, “More than Just a House,” for example) those qualities in the belle of the New South that would make possible her marriage as a type with the free “flapper” spirit of the new woman of the modern age.

Zelda, for her part, continued until the end of her life to move in and out of the dual roles of Alabama belle and free-spirited artist and writer who wanted, like Sally Carrol Happer, to be of value “when I’m not beautiful anymore.” The strain of resolving these “two sides” kept Zelda moving voluntarily in the last years of her life back and forth between her home in Montgomery and the apparent safety of Highland Hospital, the sanitarium in Asheville, North Carolina, where she died in a fire. Scott died in Hollywood in 1940, out of work as a screenwriter and struggling to complete The Last Tycoon, which remained unfinished at his death.

The afterlife of Scott and Zelda resides in their lifelong attempts — Scott’s in fiction; Zelda’s in life — to marry flapper and belle. The reunion of their mortal remains is an enduring reminder of the beauty and heartbreak of their struggle — a struggle at last ending in reconciliation.

********************

“He fancied that in a hundred years he would like having young people speculate as to whether his eyes were brown or blue, and he hoped quite passionately that his grave would have about it an air of many, many years ago.”

–This Side of Paradise (1920)

And here back in the Impala, drawing near to Rockville, Rick, Jim, and I were hoping in life to discover something we had not yet found in books. We had only been moderately vocal as we talked over our martinis earlier that night, but now, perhaps because of the solemnity of the occasion or the dimness of our job prospects or the afterglow of the martini(s) or the shaky condition of our closed-tight car — or perhaps because of all of the above — the three of us spoke more openly on the way to Rockville than we ever had in the halls of the English Department.

Zelda’s “Marriage at Cana,” from https://www.brainpickings.org/2014/04/15/zelda-fitzgerald-art/.

Rick detailed his idea that the rumors of Zelda’s family having burned her paintings were not accurate; if he could soon finish his dissertation on the Scott and Max Perkins relationship, he hoped to locate some of the paintings that no one knew existed. Jim then opened up about an extraordinary textual detail he had found in the final typescript of This Side of Paradise: Fitzgerald had intended for Amory’s final thought and the novel’s last sentence — “I know myself but that is all” — to end with a dash, not with a period, as Scribner’s first edition had ended. The dash, Jim believed, opened the ending to the promise of further development by Amory; the period closed it down, in effect yelling “The End” — a point with which Rick and I completely agreed. Jim said he was reinstating the dash in his dissertation, which was becoming an authoritative scholarly edition of This Side of Paradise.

Navigating the Impala toward Rockville as steadily and responsibly as possible under the circumstances, I followed Rick’s and Jim’s revelations with my own idea that Judy Jones had not only been the prototype for Daisy Fay Buchanan, a detail at which Fitzgerald hinted in calling “Winter Dreams” a “sort of 1st draft of the Gatsby idea.” I thought that since Daisy was from Louisville, Kentucky, and arguably a Southern belle, she was connected to Zelda as closely as she was to Ginevra King, Fitzgerald’s first serious love, who was by no means a Southern belle but who often gets the credit as his inspiration. Sally Carrol, I argued, was a version of Zelda that quickly acquired a counter-version in Nancy Lamar, also inspired by Zelda, the girl who marries the son of the razor manufacturer from Savannah in “The Jelly-Bean.” This I had already covered in my dissertation-in-progress, which I had modestly limited in scope to a discussion of each of Fitzgerald’s 170 short stories.

With our car chatter — some would say echolalia — we were in the heart of Rockville seemingly in no time, if perhaps miraculously. We stopped at a firehouse to get rough directions to all the area cemeteries in and around Rockville. We knew only not to try St. Mary’s Catholic cemetery since, as was widely known, Fitzgerald had been denied a Catholic burial. We made another stop at a 7-Eleven shortly before closing time, and we bought a case of matches (they were out of flashlights — “Sorry, you guys!”). Then one by one we went to each cemetery.

At the first there was a false sighting: Jim located a gravestone that seemed right at first by matchlight, but we soon realized that he had been fooled because he had mentally switched the photographic image of the Fitzgeralds’ headstone (a picture he was the only one of us three to have seen) with the headstone of Jay Gatsby in the 1949 film version of the movie featuring Alan Ladd, Betty Field, Macdonald Carey, and Ruth Hussey. In that movie version, Nick and Jordan talk nostalgically about Gatsby over his headstone in an outrageously extra-textual scene. All three of us had seen it and were furious that the director, Elliott Nugent, had missed Gatsby’s death on his headstone by years. So Jim had spotted the wrong grave.

We left that cemetery sad and disappointed, and then tried three more without luck.

********************

“ . . . in a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.”

— “Pasting It Together” (1936)

We arrived at the Rockville Union Cemetery on Baltimore Road, just outside Rockville itself, around two a.m. A caretaker’s cottage stood on the right, inside the gate, and a sleepy black-and-tan dog growled under his breath as Jim stepped up on the porch and knocked on the door. The caretaker, in his pajamas, pointed us reluctantly in a general direction off to the left of my car. Though we didn’t say it out loud, each of us, I am certain, wondered at the caretaker’s seeming indifference, even given the lateness of the hour, to the fact that Scott and Zelda were here in his cemetery.

I parked and aimed the car’s headlights over in the direction he had pointed, and we fanned out on foot with our matches, each one of us examining every grave we came to in our third of the fan.

Finally Rick struck a match by a gravestone and yelled, “They’re here!”

Jim and I converged on the modest, waist-high headstone, streaked dark with tree sap or mold, that Rick was kneeling beside. In his matchlight the inscription was clear: “Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald . . . His Wife . . . Zelda Sayre.”

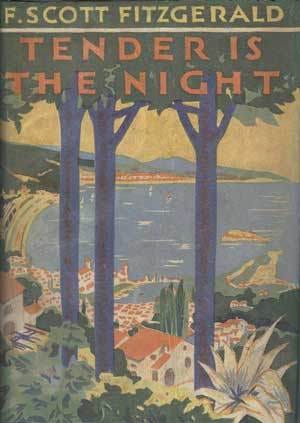

Now none of the three of us had words. It seemed pointless to ask the man lying at the foot of that stone the questions that had recently preoccupied us as graduate students: about the ampersand in “Dice, Brassknuckles & Guitar” or the hyphen in “The Jelly-Bean” title or the uppercase “I” in Tender Is the Nightor even broader interpretive issues related to the placement of the green light in Gatsbyin chapters one, five, and nine.

We were all glad when Rick went back to the Impala and brought out a bottle of George Dickel sour mash whiskey. I found Dixie Cups — Darlington-made — in the car trunk, and we toasted the Fitzgeralds with this line from Scott’s “Pasting It Together,” from his “Crack-Up” essays: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.”

After helpings of George Dickel, things went glimmering, and each of us, I am certain, experienced differently the moments that followed. I watched Rick lie flat on Zelda’s grave while Jim knelt on one knee at the headstone, like a Virginia gentleman in an old photograph.

Myself, I saw flappers come out of the earth off the dust cover of Tales of the Jazz Age and speak to each other in soft Montgomery, Alabama, voices while Rastus Muldoon’s Savannah Band began the first bars of Vladimir Tostoff’s “Jazz History of the World.” One of the flappers crooked her finger toward me in what seemed a “come hither” gesture. I did — and never looked back.

Rick and Jim argue to this day that my vision was hallucinatory, but I remain unconvinced. It seems as real today as it did that night at the grave.

********************

Monday morning after SAMLA weekend I found — source unknown — on my desk a photograph of the grave we had left behind in Maryland: a fresh photograph that had about it an air of many, many years ago. It sits on my bookcase now, its colors still vivid after many days in the sun.

I look at this picture from time to time and remind myself that Scott and Zelda are not where Jim, Rick, and I left them in the Rockville Union Cemetery. They were moved many years ago at the request of Scottie, who petitioned the Catholic Church to “re-Catholicize” Fitzgerald — to make him Catholic again — so that he and Zelda could be buried among his father’s relatives at St. Mary’s, a mile and a half from their original resting place. According to newspaper accounts, the number of visitors who typically come by the “new” St. Mary’s gravesite in any given month to pay tribute to the Fitzgeralds tripled during the month that Baz Luhrmann’s Great Gatsbypremiered in 2013.

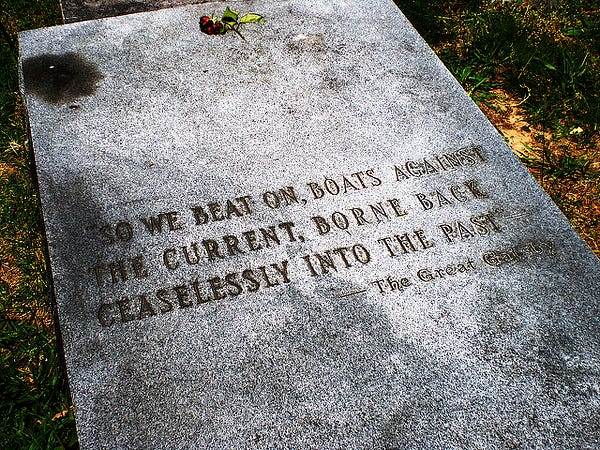

On a recent visit of my own, I was struck by one added feature of the new grave: Now in addition to the original simple headstone that was apparently moved from the Rockville site, there is a second, gigantic flat memorial stone covering the grave of Scott and Zelda — a slab almost twice again the size of the actual headstone — inscribed with the last sentence from The Great Gatsby: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

The grave at St. Mary’s, from http://www.messynessychic.com/2013/05/13/why-is-f-scott-fitzgerald-is-buried-in-a-weirdly-unremarkable-place/.

For those who visit the new gravesite, this slab no doubt offers some comfort in that it emphatically marks the reunion of the golden couple of the Jazz Age, Scott (1896–1940) and Zelda (1900–1948).

Although they had lived virtually separate lives since 1937 — hers primarily divided between Montgomery and Highland Hospital and his in Hollywood, often with his close companion, Sheilah Graham — they are finally together again in the St. Mary’s cemetery, “snuggled up together under a stone,” as Fitzgerald had hoped they would be as recently as five years before his death. It is unlikely that their physical remains will be separated or moved again from beneath what is likely a ton of granite.

The spirits of Scott and Zelda are another matter.

Novelist and legendary New Yorker editor William Maxwell, who admitted publicly that one of his great wishes was that he had written The Great Gatsby, said near the end of his life something that seems appropriate to the lives of the Fitzgeralds. He said that he believed one’s immortality is the part that lives on in the spirit of others after one’s physical death.

By Maxwell’s standard, by mine, by Jim’s, by Rick’s, and by the measure of the place Scott and Zelda and their creations have come to occupy in the spirit of American culture, there is little question that, alive and well, with their flappers and belles, the Fitzgeralds have been borne forward ceaselessly into our present.

Photo by Heather Dyan, http://www.messynessychic.com/2013/05/13/why-is-f-scott-fitzgerald-is-buried-in-a-weirdly-unremarkable-place/.

*******************************************************************************

After the Gravesite: Notes on the Personae following their own Affair of Youth

Richard Anderson is former chair and Professor of English at Huntingdon College in Montgomery, Alabama. Among his published articles are “Gatsby’s Long Shadow: Influence and Endurance” in New Essays onThe Great Gatsby, edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli; “After Tender Is the Night: A Literary Strategy for the 1930’s” in the Fitzgerald/Hemingway Annual; and “Rivalry and Partnership: The Short Fiction of Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald,” also in the Fitzgerald/Hemingway Annual. He has located and purchased a number of previously unknown paintings by Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, three of which reside in his home; and he owns a paper doll made by Zelda — a gift from Scottie Fitzgerald Smith, daughter of Scott and Zelda — that rests near an empty George Dickel bottle, also in his home in Montgomery.

Bryant Mangum is Professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University. He is the editor of F. Scott Fitzgerald in Context and the Modern Library’s Best Early Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald, which includes “Winter Dreams” and “The Ice Palace.” He is also the author of A Fortune Yet: Money in the Art of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Short Stories. His essays have appeared in Resources for American Literary Study, The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review, the Fitzgerald/Hemingway Annual, The Cambridge Companion to F. Scott Fitzgerald, New Essays on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Neglected Stories, and other books and journals.

James L. W. West III is Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English at Pennsylvania State University. He has held fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Humanities Center, and the National Endowment for the Humanities; he has also had Fulbright appointments at Cambridge University and at the Université de Liège, and he has been a visiting fellow at the American Academy in Rome. He is the general editor of the Cambridge Fitzgerald Edition, which now includes This Side of Paradise and eleven other authoritative volumes, including over 100,000 words of glosses. He edited Trimalchio: An Early Version of The Great Gatsby and is the author of The Perfect Hour: The Romance of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ginevra King.

Click here to read the full article on Medium, specially formatted for an online audience. Don’t forget to clap if you like what you read!

And be sure to sample the contents of our “Maps & Legends” issue from 2016–perhaps even order a print copy of your very own!

True stories, honestly.