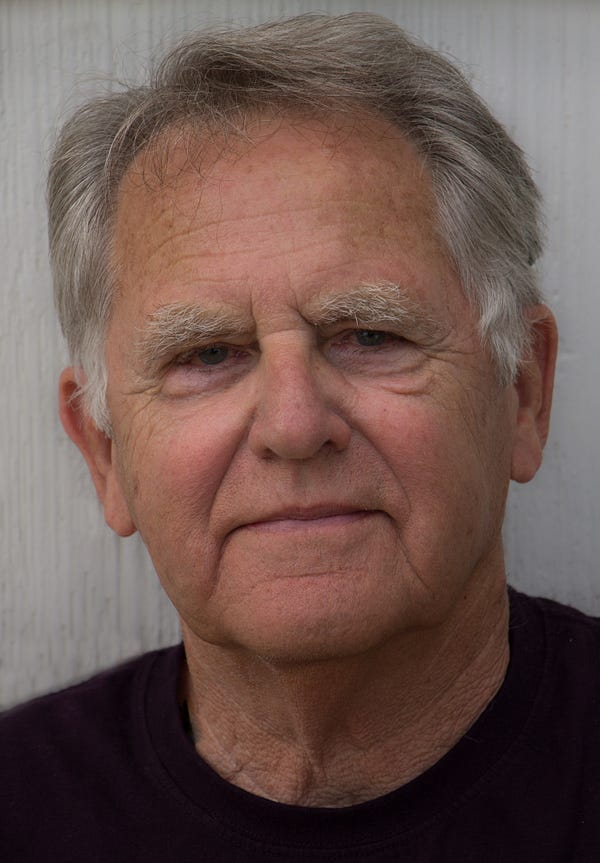

Spotlight Interview: Al Landwehr, author of “‘The Dancing Horologist’ and Ten Other Love Stories.”

by broadstreetmag on Jun 10, 2018 • 6:55 pm No Comments“Put simply, a good story helps prepare the reader for reality. If all that sounds saintly, that’s another kind of distortion.”

For over forty years, Al Landwehr has written fiction featured in publications that range from slick mass-market magazines to literary journals: Playboy, Redbook, New Letters, The Chariton Review, and Negative Capability, among others.

Now his work — stories and a novella — has been collected in “The Dancing Horologist” and Ten Other Love Stories. (Click to arrive at the book.) This book comes soon after a move from his longtime home in San Luis Obispo, California, to Astoria, Oregon.

We wanted to know about how Al sees truth playing out in his fiction, what role place has in establishing a kind of truth, and how he managed to choose among favorite children to make a “Best of Al Landwehr” compilation album.

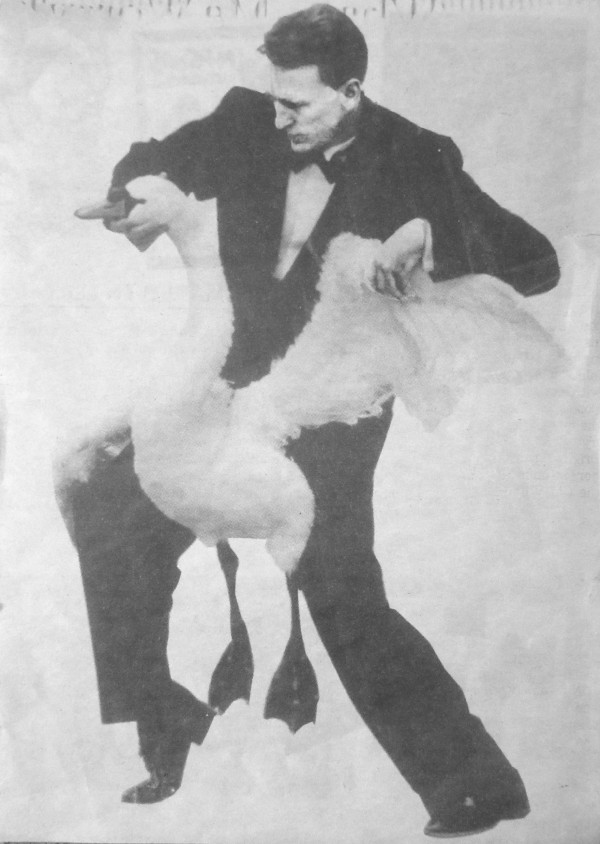

And what is a horologist, you ask? Well, that would be someone who is concerned with the measurement of time. As Al’s life has changed dramatically of late, and as his work takes off in a new direction, this is the ideal moment to take a tango with time. But the true dance partners won’t be revealed till the end of this interview … Read on!

This interview is also available, in slightly different format, on Medium.

***********************************************************************************

Broad Street: You were a beloved professor at California Polytechnic State University, where the institutional focus was on engineering and agriculture more than on humanities. The sciences and the humanities are generally believed to have very different notions of what makes Truth. Could you tell us where you find “truth” in your fiction?

Al Landwehr: I imagine at least 90% of each of my short stories, but I try to tell the truth of the human condition. I try to portray our society as it really is, and I hope that the reader will think about that world and the complex aspects of that world, deal with it as best he or she can, and enjoy it as fully as possible.

Al Landwehr: I imagine at least 90% of each of my short stories, but I try to tell the truth of the human condition. I try to portray our society as it really is, and I hope that the reader will think about that world and the complex aspects of that world, deal with it as best he or she can, and enjoy it as fully as possible.This sounds desperately serious, and at times it is, but the society in which we live is often also hilarious, and sometimes both serious and hilarious. Furthermore, the truth about human society is often distorted, and fiction should avoid and counteract distortion as well as portray that society as honestly as possible with empathy, compassion, and a sense of humor.

Put simply, a good story helps prepare the reader for reality. If all that sounds saintly, that’s another kind of distortion.

“Almost always, my stories occur to me with a word, a line, or maybe a scene. They interest me, and I let them have their head.”

I know writers love this question: Where do you get your inspiration and subject matter?

My basic process is intuitive rather than logical. I don’t sit down and think, “I’ll write a story about a man who….” I once knew an entire story before I began writing, and I wrote it, and it was terrible. I love writing stories, and just like my reader, I as the writer want to know what will happen next.

In my collection is a story titled “Tattoos,” which I wrote long ago, before tattoos were in vogue. I have a sculptor friend who, when a teenager, had inscribed a tattoo on the fleshy part of his hand between his thumb and forefinger. His tattoo made me curious. I read some books about tattoos, their history and implications. I continued to think about the subject, imagining two people with tattoos living together, thinking about the nature of their tattoos, and one day the line, “Henderson’s parents were covered in tattoos,” came to my mind. I continued to think about these two tattooed people and their son Henderson. I wrote the first draft in two days. I then revised the story about twenty times.

Not too surprisingly perhaps, the story is about Henderson, their son. I became fascinated by what kind of an adult one would become if one grew up with parents covered with tattoos.

I should add that I have a stack of stories that I haven’t finished yet, but I love this process. I do feel a little bad for the ones I’ll never finish.

“I once knew an entire story before I began writing, and I wrote it, and it was terrible.”

Now here’s the record-album question: How does it feel to put the best of your life’s work so far into one volume? Is creating this package a beginning as well as an ending?

These eleven stories are only part of what I would consider my best work. For this collection, I started by selecting published stories that I thought were good, and then I noticed that they were love stories, and I started checking to see if I had other published stories that were also love stories. Others were love stories, and then I remembered recent works I hadn’t yet tried to publish that were also love stories. Soon I had ten short stories — and a novella I’d been working on for years.

I noticed there was a progression in tone over the years, and so the stories are close to being in chronological order. That gave me some insights into my writing which have sent me into a new direction, which I don’t want to articulate because it’s not entirely clear to me yet and I don’t want to box myself in.

Although you lived long in San Luis Obispo, California, the stories tend to be set elsewhere. Is there some reason you can pinpoint for your choices in setting and your decision to steer clear of SLO here? If it’s a matter of needing some distance on the setting for your work, have you found yourself starting to think more of stories set in SLO now that you’ve moved to Oregon?

This question tantalizes me and rattles my cage. Of the ten short stories and the novella in my collection, only “Too Old to Dance” is set in San Luis Obispo. “The Dancing Horologist” is set in Los Angeles, although it has the feel of north Saint Louis, Missouri, where I was born and lived until I was about nineteen.

I was born into a working-class family and none of my relatives had more than an eighth-grade education. I essentially fled that world, going on to earn a Ph.D. and becoming an English professor for almost forty years. And yet part of me never really left Saint Louis and the working class.

The world of my youth has stayed with me, and I think that’s true of many writers; the setting of your youth leaves it impression on you. For me it’s primarily that working-class background; it has a stronger influence on my stories than does the city of Saint Louis itself.

San Luis Obispo, where we lived for many years, is not a working-class town. It’s essentially an affluent college town, which would lend itself to irony and satire, and that’s not my cup of tea. My wife, Lynne, and I now live in Astoria, Oregon, another working-class community, and I’m already writing stories set here.

I have over the years written some stories set in San Luis Obispo but not a great number. I’m curious whether, now that we live in Oregon, I will use California as a setting more often. I have done one to date, and it’s about old age and the shadow of death.

“I don’t want to articulate the new direction my writing has taken — because it’s not entirely clear to me yet and I don’t want to box myself in.”

This book includes a remarkable novella, “Merely Players,” which you describe as having some noir elements. So here come two inevitable questions: First, how do you define a novella and distinguish it from a short story or the recently fashionable and unclearly defined “novelette?” Second inevitable question: How do you define noir?

A novella is something around 25,000 words or more, but more importantly, it has a greater complexity than a short story: numerous characters, numerous conflicts, numerous plot elements, and numerous themes, although not necessarily all of these. I don’t know what a novelette is except that it sounds less elegant.

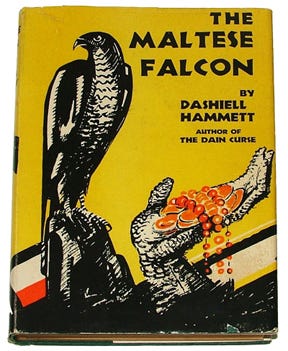

When I referred to “Merely Players” as noir fiction, I was borrowing from the genre of noir films, which, I feel, truly began with two masterful detective novels: Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep and Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, both of which were made into movies.

A noir movie or noir novel usually has a private detective who doesn’t suffer much guilt, a beautiful woman, sex, corruption, violence, and a dramatic ending. I grew up watching these noir films and loved them, and I later turned to the novelists, including Chandler and Hammett, whose works I’ve read numerous times. These two were masters of the form.

In the noir novel, aspects of the story are often streamlined rather than portraying the complexity of reality. For instance, in noir, violence often brings an end to evil and to the complexity of the situation, which is almost certainly an oversimplification of the real world. In the truth of reality, normally if a person commits an act of violence, that act results in a sense of guilt. A noir novel or a noir film conveys a darkness, but it often doesn’t deal with the psychological aftermath. That notion was a major consideration as I approached my journey into a “noir” novella — when, after years of enjoying these works, I asked myself if I should try to write a noir story myself …infused, of course, with my own perspectives and concerns.

“The world of my youth has stayed with me, and I think that’s true of many writers; the setting of your youth leaves its impression on you.”

My penchant for realism also touched a number of other aspects of the story. The result was “Merely Players,” which I think demonstrates some of my own preoccupations with truth and realism. I’m not sure it fits the category of “noir,” but that’s how I began.

Stories take on a life of their own.

Thanks for the interview, Al, and congratulations again!

Special thanks, perhaps most oddly, for this picture of a man dancing with a swan, which you seem to have found important to share with our readers … They’ll have to read the book to find out why.

(Is it possible ever to be too old to dance with a swan?)

Chair clock image: “Universal Clock” at the Clock Museum in Zacatlán, Puebla, Mexico. Wikimedia.