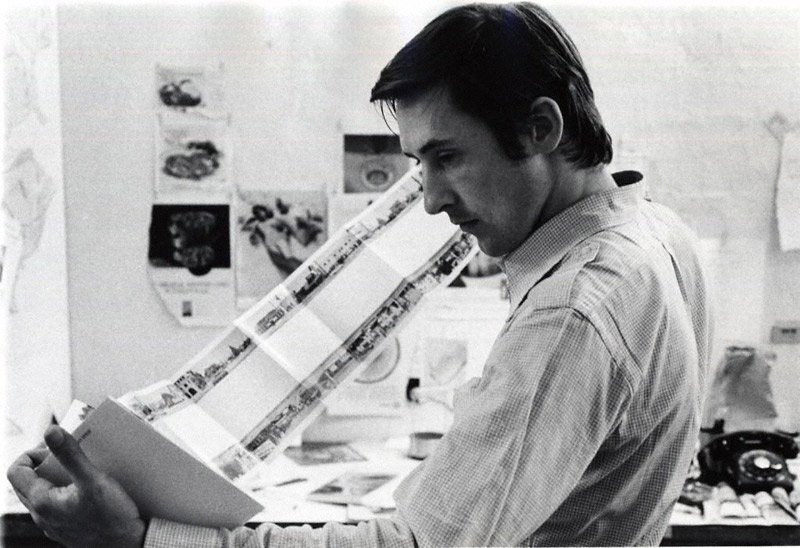

Ed Ruscha holding his book Every Building on the Sunset Strip, 1967. © Ed Ruscha. Image courtesy of Jerry McMillan and Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica. © Jerry McMillan

by Carla Dominguez

Edward Ruscha was the wrong kind of pop artist. While other pop artists were moving away from the movement’s Dadaist roots and pursuing an avant-garde image, Ruscha maintained the simplicity and quiet truth of the movement using direct, even dull, photographs and paintings.

The pop-art movement came loudly and boldly, using images and techniques of commercial art and illustration to discover artistic value and freshness in everyday aspects of American culture. Yet the Andy Warhols and Roy Lichtensteins of the movement, while taking interest in the mundane, always gravitated toward what might be called the interesting mundane: the glamour of Hollywood; the glitz of popular media; bright, saturated, flashing colors. As a result, pop art, perhaps unintentionally, celebrated and became part of the world it was portraying and sometimes parodying.

“Commercial art was attractive [to pop artists] because it was something everyone hated—but then…it wasn’t hated enough after all and quickly became accepted,” says ARTnews. The idea of simplicity and minimalism seems to have been lost.

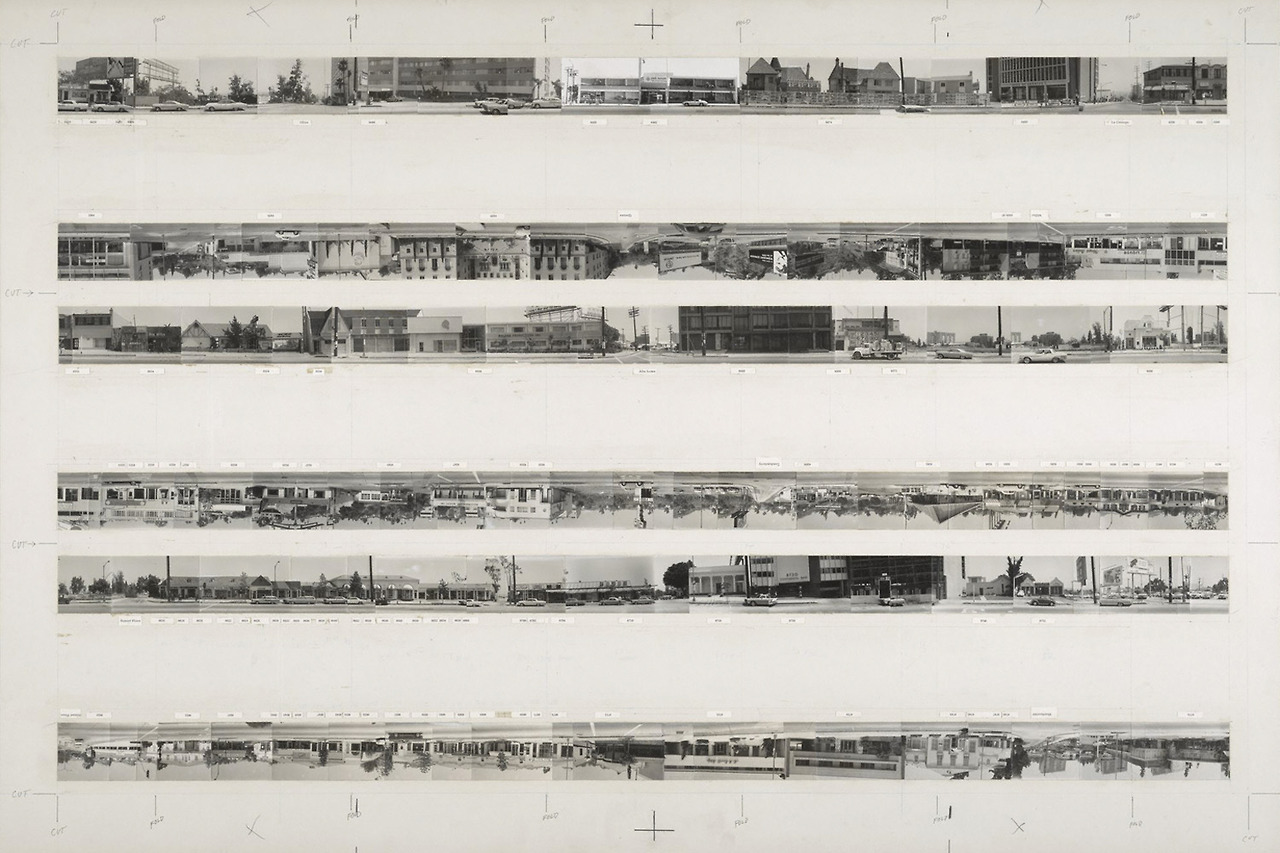

Ruscha went a different way. He made a name for himself by self-publishing books of photographs of what are probably the most unremarkable, simple, boring things known to American culture. His first book, Twentysix Gasoline Stations, is a small, chapbook style collection of twenty-six gray-scale photos of gas stations. The stations are along Route 66 between Los Angeles and Oklahoma City. “I just had a personal connection to that span of mileage between Oklahoma and California,” Ruscha explains. “It just, it kind of spoke to me.” His third book, Some Los Angeles Apartments, features thirty-four images of apartment buildings in Los Angeles.

Ed Ruscha (American, born 1937). Standard, Figueroa Street, Los Angeles, 1962. Gelatin silver print. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Among Ruscha’s other books are Various Small Fires and Milk, which presented his photos of people smoking, lighters, a trash fire, and one picture of a glass of milk; Every Building on the Sunset Strip; Real Estate Opportunities (photos of vacant lots); and Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass.

Even for the pop world, this mundane could seem too mundane. Even Ruscha’s production process was low-rent. He didn’t spend what the art world would have deemed the appropriate amount of money on creating his books. At the time, the idea of an artist making a publication was supposed to be an intimate, expensive, and limited-edition process, curator Virginia Heckert explains. Ruscha, however, mass-printed the books and sold them for $3 each. The pulp-magazine-level paper and unremarkable subjects did not present the type of “simple and mundane” imagery the pop art world was going for at the time—no Elvises or Jackie Onassises, simply vacant lots or storefronts. “People who were in the art world, like, ‘What is this you’re doing? Are you putting us on?’ ” Ruscha once recalled.

Although Ruscha’s photographs lack the drama and romanticism of other pop artists, they can tell us more about ourselves than the more chest-pounding work of Andy Warhol or James Rosenquist. We understand, and now question, that attachment to things like buildings or familiar stretches of roads.

Frank Gehry, for one, was drawn to Ruscha’s simplicity. “I thought it was so real,” Gehry says, “So laid back, so not in your face, so just: I’m just exploring things and this is how I explore things. I’m fascinated with the streetscape, so I take pictures of every building on the street and look at it.”

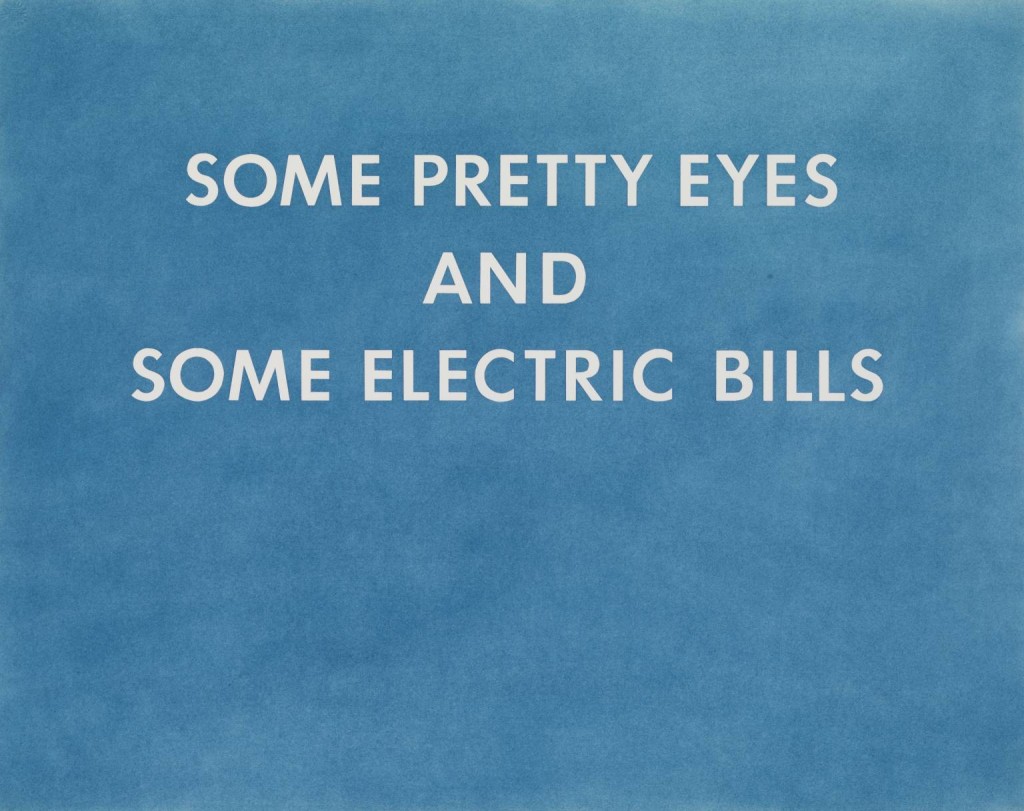

Ruscha eventually moved into painting and still managed to keep the same ideals and focused on the same type of mundane. Ed Ruscha painted words, forcing viewers to see them as isolated art forms. His famous painting Oof features “just those three block letters, each one bigger than your head, in cadmium yellow on a background of cobalt blue.” Ruscha says he didn’t paint words because of their meaning, but because he liked the way they looked. But by meticulously drawing a single word he brings attention to the way we use language and the history behind it, much like the way he brought attention to boring buildings on Sunset Boulevard.

“This idea of American culture, it’s an old one,” he said in an interview with the Guardian. “And the words and all that are just the tail end of an ancient tradition that began with man scribbling on a cave wall. I’m observing that these words, which sometimes represent objects and meanings, are made up of these squiggly little forms we call an alphabet.”

For us, both now and then, it might seem that Ruscha’s photographic work is dry and lacking in passion. But that is the point; he was fulfilling the original mission statement of the pop art movement. If you can’t get to the MoMa, Ed Ruscha has graciously provided some his artwork for your viewing pleasure on his website.