by Carla Dominguez

Sanora Babb was a writer, poet, and journalist who spent most of her adult life living in the shadow of John Steinbeck. By a strange twist of fate, the meticulous notes she took during her time visiting migrant workers in the Dust Bowl underpinned two novels: her own, Whose Names Are Unknown, and Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. One found a publisher at the time, and became a modern classic; Babb’s did not, and her story and her literary career were overshadowed and largely forgotten.

Babb and her family lived in poverty and dysfunction. She moved around often, dealt with a gambling father, and witnessed the stillbirth of her brother. Her grandfather, who taught her to read using a volume of the adventures of Kit Carson and newspaper articles about murders. Though she was unable to attend school until she was eleven, she graduated as valedictorian of her high school. She went on to become a journalist for Associated Press and moved to California to work for the Los Angeles Times. The stock market crash of 1929 caused the paper to rescind the offer, leaving her unable to find steady work and lived homeless for the next decade.

When she visited her mother in 1934, Babb was struck by how different her hometown looked. The idea of social statuses, something that she had been so aware of as a child, seemed to level out now that so many lived in poverty. The Depression had effected everybody. “I saw them standing in line for the meat and potatoes of relief,” she wrote. “I saw the people I used to know who had lived smugly in their imaginary stratas–the best people who had bathtubs and cars, the middle ones who had bathtubs and white collar jobs, the unacceptable ones who had no bathtubs [and] manual jobs or doubtful means of support—standing in line together . . . Their stricken faces, one after another in the line, looked very much alike.” It seemed no one was spared.

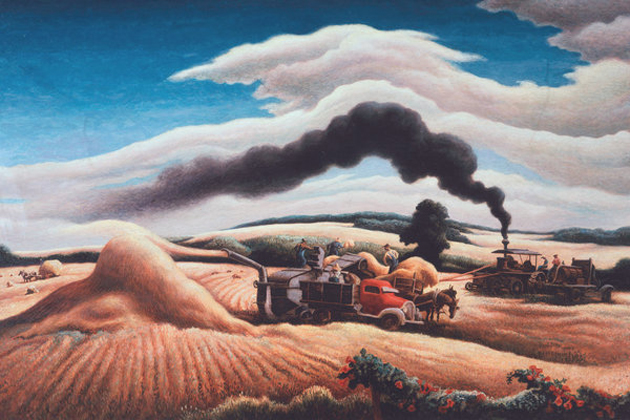

Babb returned to California and found a job in early 1938 with the Farm Security Administration. She traveled through the Central Valley with her boss, Tom Collins, providing migrants with information about programs that were in place to help them. Every night, she made extensive notes in a journal—notes she intended as resources for her planned novel about the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression, and its affects on people. These were first-hand accounts: people she had met, talked to, and helped. “How brave they all are,” she wrote. “They aren’t broken and docile but they don’t complain . . . They all want work and hate to have help.”

What she didn’t know was that her detailed notes were being secretly taken by her boss, Collins, to show to his friend John Steinbeck, who happened to be working on a novel with the same theme.

Steinbeck also had been inspired by the Dust Bowl migrants, and wanted to tell their story. He pulled a lot from what he personally saw during that time, and traveled for a short while with Tom Collins to visit migrants. As he reworked his manuscript he relied heavily on Collins’ notes, which were enthusiastically given to him. But he also relied on Sanora Babb’s notes, which Collins had passed on to Steinbeck without her permission. Babb’s retellings, interactions, and reflections were secretly read over and appropriated by Steinbeck. Babb met Steinbeck briefly and by chance at a lunch counter, but she never thought that he had been reading her notes because he did not mention it.

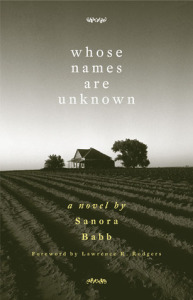

The titles of Sanora Babb’s book was derived from the eviction notice letters that would be placed on the homes of migrants.

As she had always planned, Babb used her notes as the basis of her first novel, Whose Names Are Unknown. She sent the first section to Random House, and the publishing house’s co-founder Bennet Cerf was so impressed he paid for her to come to New York City in 1939 and stay at a hotel to finish the novel. Cerf was delighted with the way the novel progressed and wrote her letters of his excitement to publish it — until Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath came out.

The Grapes of Wrath immediately took over bestseller lists. Though Babb’s work had a different feel, Random House shelved its publication plans, and gave her an advance for another novel. “Obviously,” Cerf wrote in a letter to Babb, “another book at this time about exactly the same subject would be a sad anticlimax!”

Babb was devastated and bitter. She gave up novel-writing for the next decade, focusing on short stories and literary journals. She edited The Clipper and its successor, The California Quarterly, helping to introduce the work of Ray Bradbury and B. Traven. For some of the 1940s, Babb ran a Chinese restaurant owned by her longtime boyfriend and eventual husband, James Wong Howe, an Oscar-winning cinematographer for films including “Hud” and “Funny Lady.” Although they had married in Paris in 1947, the marriage was not recognized in California because Howe was Chinese-American. When that state’s anti-miscegenation law was overturned in 1949, it took the couple three days to find a judge that was willing to marry them.

When eventually Babb returned to novel writing in 1950 she worked on a manuscript about her complicated relationship with her father. It became her first published book, The Lost Traveler, issued in 1958. Her other works include An Owl on Every Post, a memoir about her childhood; Cry of the Tinamou, a book of short stories; and Told in the Seed, a collection of poetry.

Finally, in 2004, Babb was convinced to release the original manuscript of her first book, Whose Names Are Unknown, through the University of Oklahoma Press. The book told the story of a family’s struggle to survive in Depression-ridden Oklahoma. Critics generally praised the book, noting that compared to The Grapes of Wrath, Babb’s account felt much more personal and insightful. She had approached the world of migrant workers through personal testimonials she had gathered, distinct from The Grapes of Wrath’s symbolic, dramatic approach. Douglas Wixson, her biographer, noted, “It fills a lacuna in American literature.”

Babb told the Chicago Tribune in 2004 that she thought she was a better writer than Steinbeck. “His book,” she said, “is not as realistic as mine.” Babb died on December 31, 2005, at age ninety-eight.

Steinbeck, who continued his celebrated career until his death in 1968, freely acknowledged the value to The Grapes of Wrath of contemporaneous newspaper reports and his time spent with Tom Collins. He explained that he needed these reports and firsthand accounts to create an accurate portrayal of migrant workers in the Dust Bowl. Collins was cited in Steinbeck’s dedication for The Grapes of Wrath, and Steinbeck often wrote about the work he did with him, asserting that the documents Collins provided to him were imperative to the construction of his famous novel.

Sanora Babb, and Steinbeck’s extensive use of her documents, were never mentioned.