From Our Pages: “‘It Cannot Be Conceived’: American idealists in two Chinese revolutions, Cultural and capitalist.” By Julie Anderson.

by broadstreetmag on Oct 6, 2017 • 2:08 pm No CommentsAs the U.S.’s 45th president prepares to visit China, we at BROAD STREET present a feature from our “Maps & Legends” issue–all about American idealists in China and what they found there. Culture, Communism, capitalism, espionage … Julie Anderson, who lived in Beijing in the early 1990s, untangles Sino-American relations in Pushcart-nominated essay from our “Maps & Legends” issue.

Begin the article below, or move directly to the version specially formatted and with added illustrations for the web here: “It Cannot Be Conceived.” Both versions come with photographs by Mark Wyatt.

Photo by Mark Wyatt.

******

“It Cannot Be Conceived”

American idealists in two Chinese revolutions, Cultural and capitalist.

By Julie Anderson

In June of 1966, when high school and college students in Beijing began, in the Chinese phrase, “making revolution” — beating teachers and forcing them to crawl on burning cinders, drink insecticide, wear dunce caps, and beg for mercy–the government responded by sending the small foreign community in Beijing off to Beidaihe, China’s exclusive seaside resort 175 miles east of the capital.

The foreigners had no idea what was happening in Beijing’s schools, and the mood on the six-hour train ride to Beidaihe was festive. According to the American couple David and Nancy Milton, who wrote about the trip in a memoir called The Wind Will Not Subside: Years in Revolutionary China 1965–1969, “straw hats, fishing poles, and oiled paper umbrellas filled the overhead racks, and baskets of every description overflowed with swimming suits, knitting, and the paperback detective stories beloved by the Beijing foreign community.”

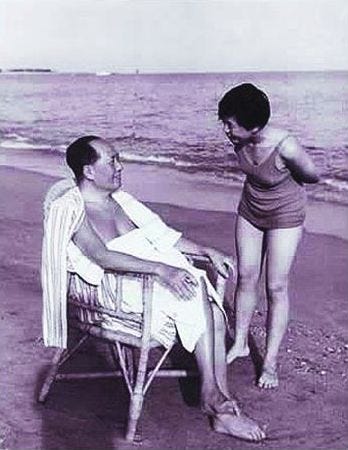

Mao and niece at Beidahe, 1960. Wikimedia.

During that summer, the events in Beijing seemed distant and dreamlike to the expatriates. Only one event made an impression on them as they relaxed on Beidaihe’s warm yellow sands: Mao Zedong’s historic swim, at the age of seventy-three, down the Yangtze River on July 16 of that year. For the Chinese, this symbolic event heralded the return of Mao Zedong to power, the beginning of his emergence as a god. For the foreigners in Beidaihe, it was — at least, initially — far simpler than that. Mao’s swim gave them permission to relax and enjoy time spent splashing around in the sea.

Growing up in the second half of the century, I had always assumed China was completely closed off to foreigners during the Cultural Revolution. Then one day in graduate school, Frederic Wakeman, the late and eminent professor of Chinese history, overturned that assumption with a simple anecdote. A British friend of his had recently traveled to China and shocked a cabdriver when he hopped into a taxi and explained where he wanted to go — in perfect Beijing street slang. The cabbie was so taken aback that at first he was unable to speak, let alone drive: How could this waiguoren, this outsider, be talking like someone who grew up in the alleyways of Beijing?

Listening to Dr. Wakeman, I wondered the same thing.

******* (Text is abridged here; see the full version online to get more about early expats.)

In 1991, two years out of college, I set off on my own journey to China, to teach English at a small university called Beifang Gongye Daxue (North China Institute of Technology), on the outskirts of Beijing. Unlike the idealistic foreigners of twenty-five years earlier, however, I didn’t want to be a Communist; I was too jaded and cynical a child of the 1980s for that (think Yuppies, Wall Street, Reaganomics, Madonna). It’s more like I was curious to see this dying world whose goals, as I understood them — free health care, education, food — I admired. I mean, who doesn’t want to eradicate poverty and make sure everyone has a shot at a decent life?

It sounded good to me in principle, even if I already knew that Communism hadn’t turned out terribly well in practice worldwide. The democracy protests in Tiananmen Square, the fall of the Berlin Wall, Glasnost — all of this had happened just a couple years earlier. Still, like those earlier foreigners, I yearned for a better place, a better life, a better version of myself, and though I didn’t want to admit it, some small part of me hoped that maybe, just maybe, I’d find this in China — even though I knew the dream was flawed.

I yearned for a better place, a better life, a better version of myself … just maybe, I’d find this in China.

Accordingly, that August, I left New York City and found myself in a nearly deserted airport somewhere outside of Beijing. The airport was tiny — about half the size of one of the terminals at JFK — and reeked of ammonia and old cigarettes. I kept looking around for more of it, as if, somewhere, another ten terminals existed that I had somehow managed to miss. How could this be the airport of a major world capital? Instead of people, the noise of cicadas filled the place; their insectile hum would rise to a deafening pitch then recede, only to start over again a few minutes later.

Suddenly, out of nowhere, a gaunt man of thirty dashed toward me and grabbed my hand in an enthusiastic handshake that lasted several seconds. He wore a cheap black polyester suit with a white button-down shirt, and he had thinning hair and a smile that managed to be both goofy and arrogant. He introduced himself as Mr. Wu and explained to me that he was the waiban of Beifang Gongda, which basically meant that his job was ensuring that the six foreigners on campus — four Japanese and two Americans — were happy.

Outside the airport, in Beijing’s damp, fierce August heat, a black sedan waited for us. The sedan, with its white-walled tires, chrome trim, and tail fins, looked straight out of the 1950s. Lace curtains covered the windows but I peeked out occasionally as Mr. Wu rattled on, eager to practice his English.

This turned out to consist of an astonishing string of proverbs and clichés.

“Your plane was a little late,” he said, “but better late than never. At any rate, you will have plenty of time to adjust to life in China. After all, Rome wasn’t built in a day!”

Mr. Wu beamed at me to assess the effect his words were having.

I smiled back politely, wondering how long it had taken him to memorize these silly phrases. I didn’t yet understand that one of the marks of an educated person in China is a mastery of chengyu — idioms and allusions — liberally sprinkled into speech. (In fact, they’re so important a part of Chinese education that there are, to this day, chengyu competitions and even TV game shows.)

In Chinese, there’s an expression: Bu ke si yi — “It cannot be conceived.” In other words, it was beautiful beyond imagining.

Satisfied with my reaction, Mr. Wu continued. “It has been raining cats and dogs here. As you know, when it rains, it pours! But now the rain has stopped and I am on cloud nine.”

I nodded and continued my furtive peeks out the window. Where were the tall buildings and lively streets of a world capital? The billboards? The souvenir shops and boutiques and nightclubs? Where on earth were the crowds of people?

All I saw when I looked out were dusty lanes and high-grown green fields. On the road, we passed industrial-sized trucks with mammoth wheels, donkey carts piled with hay or watermelons, whole families — two parents, a grandparent, one child — perched atop a single bicycle, but pretty much no cars. Shit, I thought, does Communism seriously mean we’re back in the Dark Ages?

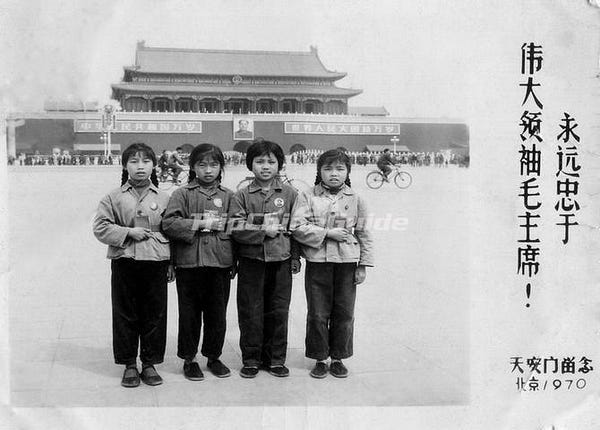

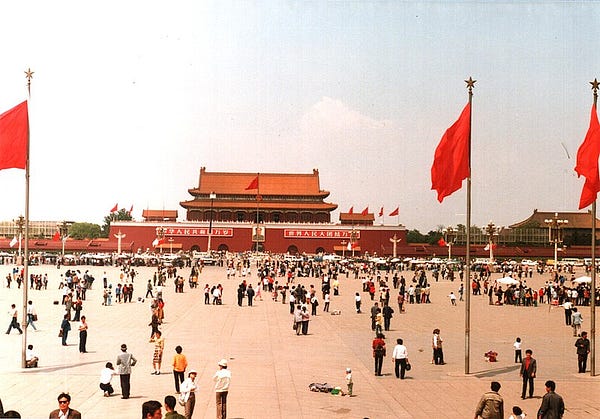

Farther along, gray brick walls and small roadside restaurants appeared, the number of bicycles increased, and the streets widened. A handful of tall buildings appeared on the horizon. Then, all at once, the road cracked open into an enormous square plaza, concrete acreage spreading on and on for what seemed like miles. On one side of us stood a line of flagpoles with giant speakers. On the other loomed ancient buildings — blood red with upturned eaves — and from the middle of the grandest building hung that famous portrait of Mao Zedong with his secretive Mona Lisa smile and those eyes that followed you everywhere.

“Tiananmen Square!” Mr. Wu cried. “We are now in the very center of the city!”

With a jolt, I realized we were passing the very place where the massacre of hundreds, maybe thousands, of students had taken place just two years earlier, in the spring of 1989. The students had been peacefully protesting the Chinese government, demanding greater freedom of speech and more government accountability. In response, the Communist Party had sent soldiers into the square (whose name translates, ironically, to the “Gate of Heavenly Peace”) to gun them down.

Now, though, any trace of the massacre had disappeared. Instead, the square was filled with what looked like Chinese tourists milling around, smiling and taking photos. I couldn’t reconcile the scene in front of my eyes with what had happened not long before. One image from televised news especially kept running through my head: that of an unknown man holding shopping bags in either hand, a man who’d singlehandedly stopped a line of tanks on the very street where we were now driving, right next to the square.

“Yes,” Mr. Wu continued, mistaking my horror for awe. “It is a sight for sore eyes.”

A few minutes later, we were past the square, surrounded again by fields and hills rising gently to the west, just beginning to be touched by the fall colors for which Beijing is so famous: fiery reds, brilliant oranges, imperial yellows. It was beautiful. Totally, unequivocally beautiful. In Chinese, there’s an expression for this: Bu ke si yi — “It cannot be conceived.” In other words, it was beautiful beyond imagining.

Like what you’ve seen so far? Read the full article here. Don’t forget to clap to show your approval.

And follow up with Julie’s Truth Teller Spotlight interview here. You’ll find out what she thinks of truth, honesty, and the writing life.

***********

Julie Anderson’s essays and stories have appeared in Writers on the Job, The Gettysburg Review, Other Voices, To-Do List Magazine, and Writing From the Inside Out, as well as various anthologies. Her Ph.D. research addressed the element of orality in classical Chinese, Greek, and Roman poetry. She lived in China in the early 1990s.

Julie Anderson’s essays and stories have appeared in Writers on the Job, The Gettysburg Review, Other Voices, To-Do List Magazine, and Writing From the Inside Out, as well as various anthologies. Her Ph.D. research addressed the element of orality in classical Chinese, Greek, and Roman poetry. She lived in China in the early 1990s.Mark Wyatt, who contributed three photographs to this piece, has been roaming the world and taking street photos for over thirty years. You can see more of his work on various blogs and crowdsourcing venues.

Author photo credit: Polly Lockman.

*************

Like what you’ve seen so far? Read the full article here.

And follow up with Julie’s Truth Teller Spotlight interview to get her take on truth, honesty, and the writing life.

True stories. Honestly.