Online Exclusive: “School of Hope and Glory: Britain’s Imperial Mission and How One Public-School Lad Failed It.” By David H. Mould.

by broadstreetmag on Nov 18, 2017 • 6:24 pm 3 Comments“At Caterham, the main instrument of social control was fear…”

BROAD STREET takes a peek into 1960s public-school life, British style, courtesy of David H. Mould and an earworm of “Pomp and Circumstance.” So-called public schools were incubators for bullies, and they were supposed to teach boys how to become men. This Online Exclusive is lavishly illustrated with photos, postcards, and memories that will make you shudder in your dormitory cot. The bullies will always be with us; but this painful, witty memoir sees a paradoxical up side.

Click here to read the full story in large print, or enjoy the same material below.

“School of Hope and Glory: Britain’s Imperial Mission and How One Public-School Lad Failed It.”

By David H. Mould

Pompous Circumstances

It was late May at Ohio University, and the Office of Public Occasions was gearing up for its biggest event of the year — the annual commencement ceremonies. A steady flow of messages landed in my mailbox — the order of ceremony, biographies of commencement speakers, outstanding graduates to be recognized, invitations to graduation receptions. There were informal dress rehearsals on the college green, with students in cut-offs and halter tops gallivanting around in robes and throwing their mortar boards into the air as if they’d already graduated.

This is the order of things academic, the events and emotions similar every year. But I was now fifty-eight years old and contemplating another type of commencement — my retirement. On the brink of a new stage in life, I started thinking about an earlier one: my nine years in a British boarding school.

As usual, I was not in the commencement mood. I secretly hoped the pigeons would poop on the student parade on the green. But it was not just the caps and gowns and misguided hopes of the graduates that made me feel queasy. It was fear of sound. Specifically, that one piece of classical music almost everyone can hum, even if they don’t know what it’s called.

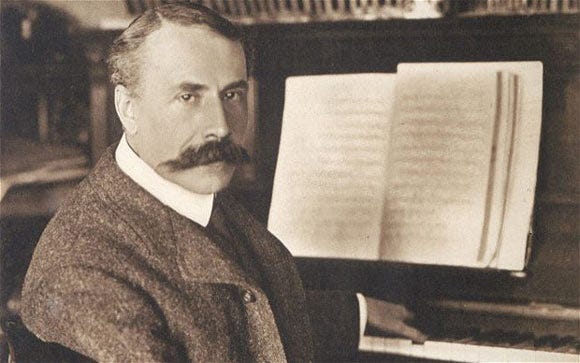

Sir Edward Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance March №1,” originally composed to mark the coronation of the British king Edward VII in 1902, is the traditional choice for commencement ceremonies, and it’s easy to understand why. It has a catchy melody, yet is serious and somber enough to mark an important day. It’s got lots of pomp, which may be appropriate. What bothers me is the circumstance.

Elgar’s original march had no words. They were added later by A. C. Benson (1862–1925), who had written a longer poem for the finale of the Coronation Ode. “Land of Hope and Glory” became a popular patriotic number, often sung as a hymn. It’s a classic tribute to the era when Britannia ruled the waves. The chorus asserts that the British Empire is not only divinely ordained, but destined to expand:

Land of hope and glory,

Mother of the free,

How shall we extol thee,

Who art born of thee?

Wider still and wider

Shall thy bounds be set.

God, who made thee mighty,

Make thee mightier yet.

God, who made thee mighty,

Make thee might-i-er yet.

These lyrics should be unsettling not only to history buffs (who may take a more nuanced view of British imperialism and nineteenth-century geopolitics), but also to anyone who remembers that the U.S. actually had a revolution and threw out the British. Perhaps it’s fortunate that few people know the words. In effect, “The Star Spangled Banner” would be followed by a rousing tribute to British colonialism.

I remember the words because “Land of Hope and Glory” was a regularly scheduled hymn at morning assembly at Caterham, the British boarding school I attended starting in the late 1950s. The entire school body sang it with gusto, but without thinking about what it meant in a world where the bounds of the British Empire (now called the Commonwealth) were fast shrinking as colonies from the Caribbean to the Pacific declared independence.

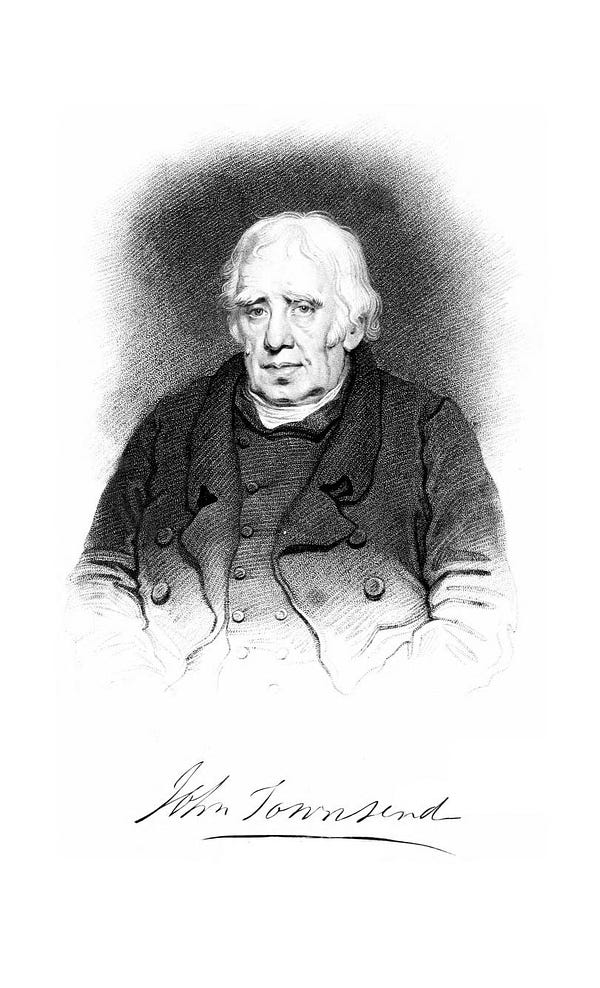

“Land of Hope and Glory” did not seem out of place in an all-male school that dated back to 1811, when it was founded by the Reverend John Townsend; a school where teachers wore robes to class, cricket and rugby were the sports of choice, discipline was enforced with the cane, and being bullied both physically and mentally was part of learning to be a man.

This is why I’ve always felt uneasy about an American commencement’s physical trappings — its pomp and circumstance. The black gowns with their colored trim, the hoods, mortarboards, and tassels, evoke painful memories. On stage, with the ceremonial mace and the throne, the university bigwigs with purple and green velvet hats and gold chains look as if they have stepped out of an amateur production of The Merchant of Venice. But this is not Shakespearean comic relief.

To me, the regalia symbolizes a culture I thought I had left behind when I arrived in the U.S. as a graduate student in 1978. It was a culture where — from the House of Lords down to the morning assembly at my school — robes and hoods denoted a system of class and privilege. This is why I have steadfastly refused to buy my own cap and gown. I’ve rented regalia each time I’ve needed it — I just don’t want those items hanging in my closet.

Each time I sat and listened to the opening bars of Elgar’s hit, I felt (delightedly) indebted to generations of soccer fans for subversive lyrics to the tune. All over England, fans customize the lyrics to scorn their opponents and celebrate the home team with versions such as this:

We hate Tott-en-ham Hotspur,

We hate Sunderland too.

We hate Man United,

But [your home team’s name here] we love you.

Each year that I sat through commencement, my mind drifted back to those nine impressionable years at a British boarding school, the years that defined my complicated relationship with pomp and circumstance.

How shall we extol thee, who are born of thee?

I can proudly say that I’ve never spent a day or night of my sixty-plus years in prison. Looking back, this seems like a fair balance, because I spent what might have been my best juvenile years in prison.

”British public school” is a phrase that alters greatly in translation to the U.S. These are fee-paying schools (although some receive government subsidies) attended by both local children who go home at the end of the school day and boarders who are stuck there until the end of the school term.

The British Empire, as Rudyard Kipling and other Victorian authors would have us believe, was forged on the playing fields of the nation’s leading public schools. It was there that the nation’s future military and political elite learned discipline, loyalty, and honor, honing their leadership skills in classroom debates and on the rugby and cricket fields.

Being bullied both physically and mentally was part of learning to be a man.

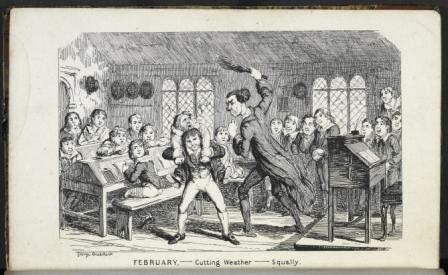

Discipline was strictly and physically enforced — officially with the cane, unofficially with institutionalized violence. There were no pesky social workers or school psychiatrists fretting about the effect of bullying on children. It was the norm. You accepted it until such time as you were in a position to administer it yourself.

Public school was not only (or even mostly) about education. It was about building character and resilience. The upper classes sent their children to public schools. According to the inexorable law of social mobility, middle-class families aspired to rise in status. And so they aped the upper classes by packing off their kids too.

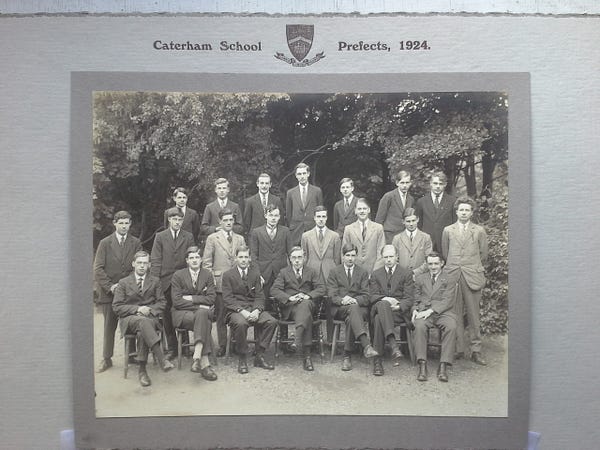

My father, Ernest Harley Mould, was the kind of boy whom Kipling meant when he praised public school. Dad went to Caterham, in a leafy, semi-rural setting south of London, in the early years of World War I. Outgoing and athletic, he was given positions of leadership, played on the field hockey and rugby teams, and for his final two years served as a school prefect. He also did well academically, and in 1924 he “went up” to King’s College, Cambridge, and then on to a long and successful career with the City of London Corporation, the authority that since Anglo-Saxon times has administered the original heart of the city — today, the so-called “square mile” or financial district. He credited his Caterham School education for his career skills, cultivated accent, and social graces.

I, on the other hand, was quiet, shy, overweight, unathletic, and bookish, lacking confidence and social skills. In my parents’ view, this was exactly why I needed to go to public school. Away from home, discipline and competition would force me to stick up for myself in the classroom and on the playground. It would draw out my best qualities. No one knew exactly what these were, but it was assumed I had some. In short, it would make a man out of me.

And so, in August 1958, at the age of eight and three-quarters, I was packed off to Caterham. I would not see my parents or sister, Liz, again until the Christmas holidays. And I would not escape permanently for another nine years.

Looking back, I think there wasn’t much difference between a British boarding school and the sort of minimum-security facility where the U.S. government sends white-collar criminals such as Martha Stewart. Except that I was with a much more dangerous crowd — pre-teen and teenaged British boys with an attitude.

Wider still and wider shall thy bounds be set …

From the outside, the Victorian-era buildings of Caterham look rather like Harry Potter’s Hogwarts. In my memory, they appear stately and imposing, with towers and porticos, long, dark corridors, high ceilings, deep windows, broad wooden staircases, and stone steps. Through the photographer’s lens, they resemble mansions where the aristocracy might live, ringing bells to have butlers, footmen, valets and ladies’ maids come running to serve tea or to dress them for dinner. And maybe that’s how they were a couple of hundred years ago.

But my Caterham was not Hogwarts, where a bright, enterprising boy can excel and stretch his imagination. It was more like a dark, twisted version of an aristocratic stately home where rank and privilege dictated behavior and where none of the servants — I’m sorry, I meant to say students — dared speak up against the system. Imagine a slightly seedy, down-market version of TV’s Downton Abbey. Then throw out the well-meaning Lord Grantham and his kin, and turn over the management to a bunch of thuggish snobs. That was the Caterham I experienced.

Caterham would draw out my best qualities. No one knew exactly what these were, but it was assumed I had some.

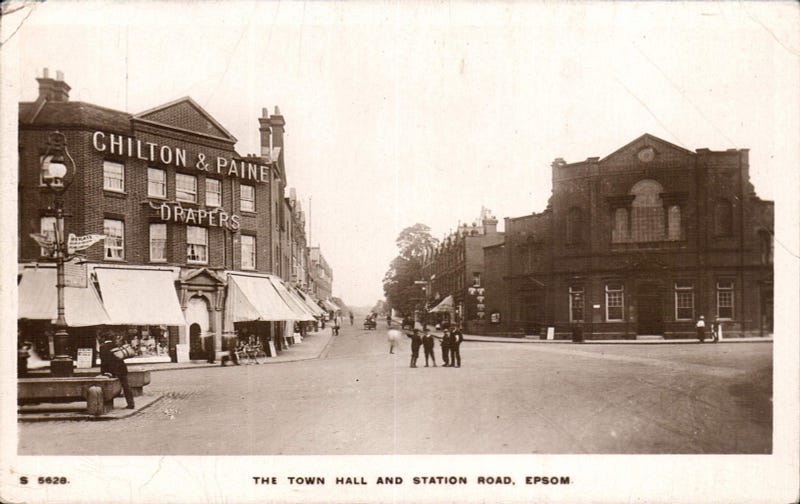

I came from Epsom, a London suburb famous for two things: Epsom salts (their value vaguely defined) and the track where Britain’s richest race, the Epsom Derby, has been held since 1780 — incidentally, my mother’s favorite destination for what she called “a flutter on the horses.”

Epsom is in what is still called the “Surrey fringe.” That’s not “The Surrey with the Fringe on Top” from the 1943 Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Oklahoma!; my Surrey was a lot less exotic than Oklahoma. It’s a county in southeast England, and at that time it lay on the southwestern edge of London, thus the “fringe” description. Since then, the metropolis has pretty much gobbled up both the fringe and Surrey itself; the real fringe is fifty miles farther south and west, where commuters begin their morning slog into the city by train and car at 5:30 a.m.

In the 1950s, Surrey was, if not like Oklahoma, at least a little rural; there were still farms among the rows of semi-detached (duplex) houses, woods and green space, and not much traffic. A safe if nondescript and unexciting place to grow up.

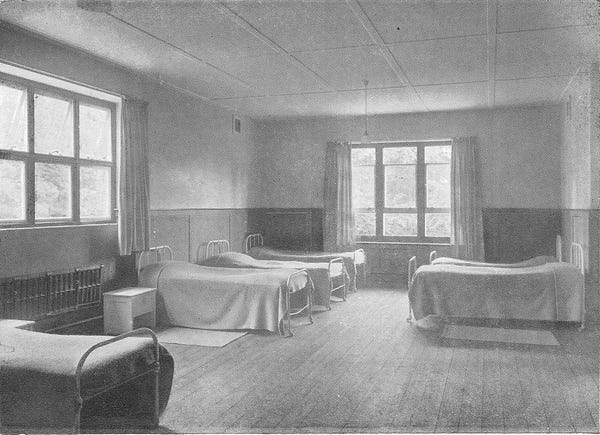

At home in our apartment, everything was familiar and to human scale. At Caterham, I felt overwhelmed by the vastness of the place. At home, I had my own small bedroom, and my dog, Tommy, would curl up under the covers with me.

At Caterham, I was assigned a bed in a dormitory — a large, drafty room featuring twenty to thirty metal-framed beds with thin mattresses. The older and/or more assertive boys claimed the beds by the windows so they could sneak out onto the roof to smoke. The rest of us were consigned to the anonymous middle of the room. Beside each bed was a small locker for personal items. This was subject to search, and the items in it to seizure, at any time without warrant or cause. Most searches were carried out by older boys who stole whatever candy or cash you had stashed. That was bad enough. What made it worse was that such actions were officially sanctioned. Many of the thieves were monitors and prefects, appointed to maintain discipline among the younger boys.

The first time it happened, I went running in tears to the house master. He was not sympathetic, saying he was sure there was a good reason for the search.

“Stop sniveling,” he ordered. “You need to learn to stand up for yourself.”

For a moment, I decided to do so.

The thugs were waiting outside the teacher’s study. “We’ve got a lesson for you,” said the gang leader. They dragged me behind the bike shed, beat me up, and extracted a pledge.

“Yes, I promise never to snitch again,” I blurted out through the tears.

And I kept my promise, because at Caterham, the main instrument of social control was fear. As in any other authoritarian regime — a coal company town, a military unit, a prison — your best chance for survival was to obey orders without question, keep your head down, and accept your punishment without complaint.

Bullying took many forms. There was the obvious, physical kind. Victims showed up at the school infirmary with black eyes or bloody noses, claiming they had tripped and fallen on their way back from class or had suffered the injury on the rugby field: “Matron, I was on the line trying to make a tackle and the goal post just jumped up and hit me in the face.”

More often the bullies did not leave marks. They twisted your arms behind your back or applied what was called Chinese wrist torture, energetically squeezing your lower arm in a circular motion. Now and then, you would hear rumors of acts of sadism or sodomy, but you never knew if they were true. The bullies always liked to brag, and telling outrageous tales of their cruelty served to reinforce their power and status.

You were probably not sure what offense you had committed. Although the bullies were sometimes after your candy or your pencil set, most often they picked on you simply because you were there. Because you did not step aside on the path to let them pass. Because you were talking. Or because you were not talking. Because you did not acknowledge them. Or because you did: “Hey, fatty Mould, what are you looking at?” It was random and unpredictable.

I was called weak, stupid, ugly, and a hundred other adjectives. I had no right to take up space in the room, or even to breathe the air. My lean, athletic father would have put the bullies in their place, probably on the floor. I ran and hid, but they almost always found me. Looking back, it all seems so juvenile. But I was a juvenile, and it hurt deeply.

The bullies had a field day with my surname, “Mould,” with all its connotations of decay and slime. “Mouldy, pouldy, pudding and pie,” they chanted in a variation of the old English nursery rhyme “Georgie Porgie.” The name’s origin, incindentally, is Flemish; in the eighteenth century my father’s ancestors were weavers in Brussels, where it would have been pronounced “Muldt,” which is not exactly pleasant but at least less open to ridicule than “Mould.”

Naturally, the bullies were not interested in etymology, only (in the grand tradition of bullies worldwide) in making me feel small and worthless.

In my personal gulag, time seemed to stretch out into an ungraspable eternity.

How did I put up with it? Sitting in my rented regalia in Ohio University’s cavernous Convocation Center with the band playing “Pomp and Circumstance,” I recalled a phrase from Alexandr Solzhenitsyn’s gulag memoir, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. I’d read it in my sophomore Russian literature in translation class at university: “The days rolled by in the camp, but the years they never rolled by: they never moved by a second.”

All right, all right. I may be making an unjustified literary stretch to compare my years at Caterham with the life of a zek (convict) in a Stalin-era labor camp. But Solzhenitsyn’s descriptions of camp life vividly capture the sense of an unrelenting routine with no end in sight.

Public school was not only (or even mostly) about education. It was about building character and resilience.

I kept a calendar, and later a diary, checking off each day and calculating how many were left until the short midterm break or the end of the term. Marking the days gave me a false sense of control over time. I could look forward to the summer holidays, but I knew that in August I would be back for another year.

Just as the school day was divided into time periods for subjects, so the time before and after classes was regimented. A typical day began at 7:00 a.m., when the head prefect walked up and down the corridors, ringing a large hand bell. I slipped out of bed onto the cold hardwood floor and, still shivering, joined the line at the wash basins. I put on my school uniform, made my bed, and waited for a monitor to inspect it, perhaps reprimanding me for an untidy hospital corner or an orphan sock.

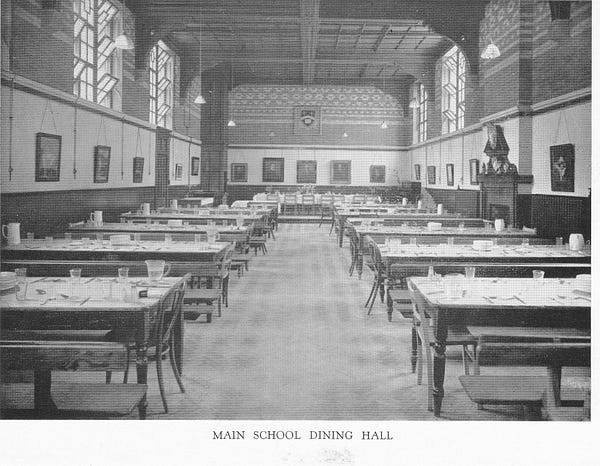

Breakfast from 7:30 to 8:00 was almost always gray porridge, washed down with strong, sweet tea. I shined my shoes, then walked to morning assembly, followed by morning class.

Afternoons and evenings were similarly segmented, with slots set aside for quiet reading and group radio listening. We huddled around transistor radios, trying to tune in pop music on the elusive Radio Luxemburg and later pirate stations in the North Sea; on Sundays at 4:00 p.m., we listened to the top twenty on Alan “Fluff” Freeman’s Pick of the Pops, the BBC’s only concession to teenage taste.

Once a month we had the right to actually leave the premises, walk the mile to the village of Caterham, and spend our pocket money (if it hadn’t been stolen).

Roll calls were frequent. There was a lot of signing in and signing out. Every day followed the same pattern.

In such circumstances, some people could go crazy. I don’t know whether or not I suffered from depression, although I remember crying a lot.

The standard remedy was not a sympathetic ear or a cup of tea, but a reprimand: “Grow up and snap out of it.”

The art teacher reminded us that he had “grown up in the slums of Manchester” and had had it a lot tougher than any of us pampered middle-class boys.

I decided I didn’t like art.

God, who made thee mighty …

If you don’t like art and don’t want to go insane, what do you do? Well, there’s always religion, which has often provided comfort and hope to the incarcerated. Religion was not a personal choice at Caterham because you had one specific creed shoved down your throat whether you liked it or not. On Sunday, you attended either the Anglican (Episcopalian) or Congregational Church; atheism and agnosticism were not options.

The school was founded in 1811 in Lewisham (now an inner London suburb) to educate the sons of Congregational ministers. By 1884, it had outgrown its premises and the 114 boys and their teaching staff moved to the present location in Caterham. In 1890, it started admitting the sons of laymen and day schoolers in addition to the spiritual elite. Although it was officially a secular establishment, attendance at religious ceremonies, beginning with the daily school assembly, was compulsory.

Note that I use the word attendance, not participation; you can force people to show up for an event but you can’t make them take part in it. It was a formal occasion held in a chapel, the boys assembled, according to class rank, in long rows. The processional announced the arrival of the teachers, who walked down the center aisle to take their seats, also denoted by seniority, on stage. There were hymns, prayers, and routine announcements about classroom changes and club activities.

We dozed through homilies from the headmaster, who had a habit of stretching theological logic to justify the school system. It was indeed a revelation to learn that a verse in the Old Testament prohibited drinking beer behind the gymnasium. Or that the twelve apostles would have shown up to cheer on the school cricket team on Saturday afternoon, which was why we had to show up too.

Although we didn’t think about Britain’s imperial mission and Kipling’s “White Man’s Burden” at the time — and certainly none of the teachers encouraged such critical reflection — when we sang the hymns at the Caterham school assembly, we tacitly accepted that Britain knew best and had God on its side. For two centuries, British colonialism had been underpinned by religious and moral rhetoric in which the colonizers were Christian soldiers out to help the peoples they conquered. Expansion was not about South African gold or India’s cotton, silk, and tea, but about rescuing the natives from their barbaric customs, even if it meant enslaving them on plantations or in mines (or public schools) for their own good. As Caterham boys, we were destined to be the new generation of Christian soldiers — even if we merely ended up pushing paper in a government or commercial office.

We tacitly accepted that Britain knew best and had God on its side.

In the equivalent of the eleventh and twelfth grades, most boys — the future bankers, political leaders, soldiers — were appointed as prefects and monitors, assigned to police the younger boys. The ranks came with privileges such as the prefects’ study, where the chosen ones could slouch on worn couches, administer threats and beatings, play vinyl records, and read Playboy without being disturbed. They indulged in risky cuisine, using the gas fire as a broiler; if the study had a distinctive odor, it was a mix of sweat and burned toast.

I, of course, kept my head down and hoped I would not be noticed. I sought refuge in the library, where the code of silence was accepted; even the meanest bullies would not dream of confronting me in the stacks. In some ways, I succeeded: Academically, I did well, but in every other measure of school achievement I was written off as a misfit, certainly not leadership material.

I don’t know whether or not I suffered from depression, although I remember crying a lot.

The prefects made those who did not make the leadership cut feel our lack of status intensely. Puffed up by their new power, and wearing the symbolic robes, they strutted around like peacocks, issuing senseless orders and meting out unjustified punishments. I wondered how they would behave when, as the public school system ordained, they ended up in positions of responsibility in government, the military, and business.

Well, at least it might hasten the end of empire. which my reading had already convinced me would be a good outcome.

… Make thee mightier yet.

I once mentioned my public-school diary to a fellow memoir writer. “Pure gold,” she said. Maybe so, but I haven’t yet plucked up the courage to read it. I’ve spent so many years trying to block out my experiences that I’m not sure how well I can process them. Maybe I’m afraid that when I open the diary, I’ll unearth other bad memories. For now, this essay is as far as I can go.

I’m well aware that my comments should not reflect on today’s Caterham. I know the place has changed. Most notably in 1995 when, after 184 years as a boys’ day and boarding school, it merged with a girls’ school to become co-educational. I’m sure it has some excellent teachers, and that the students have more out-of-class activities and freedom than I had. I just don’t know. I can write only of my own experiences and how I remember them. And I know that memory can be faulty.

Even back then, the public-school experience was not the same for everyone. My mental map of the school’s buildings and playing fields is fuzzy, blurred, out of scale. My oldest friend, Alan (he arrived at Caterham in 1961), intimately recalls the layout of the buildings and classrooms, and even the hilly, wooded area behind the school where some boys built secret dens from scraps of wood and corrugated metal.

Alan, who came from a rough, working-class background, does not recall the past to celebrate it. He probably had as difficult a school experience as I did, but he has learned to live with it better than I have. We each deal with our past in different ways. He recalls key moments from his school experience, naming the people involved and even telling me what happened to them in later life:

“He dropped out but later went on to get his Ph.D.”

“He ended up driving a mobile grocery van in northern Scotland.”

Alan can also recite the names of the boys in his class in roll-call alphabetical order. If memory is always selective and constructs a life story with which each of us can live, Alan seems to have mastered the process. He was stronger, mentally and physically, than I was, and stood up to the Caterham bullies.

My left-leaning politics, my commitment to social justice, and lack of deference to hereditary power and authority — all that can be attributed, paradoxically, to the Caterham years.

If I had the opportunity to discuss Caterham with my parents today (they both died in the mid-1980s), here’s what I would tell them: Those nine years were the unhappiest of my life, but in retrospect they had a positive impact on me. It was certainly not the one intended, but I survived, and I was probably better for the ordeal. What does not kill us makes us stronger. I went on to university and a fulfilling career in journalism and, later, academe.

However, the system of class and privilege I first experienced at Caterham left a lasting impression. I cannot share the values of my father and his peers, growing up in the empire on which the sun never sets. My left-leaning politics, my commitment to social justice, and lack of deference to hereditary power and authority — all that can be attributed, paradoxically, to the Caterham years.

And, yes, so can that queasy feeling in my stomach when I hear “Pomp and Circumstance.”

****

Caterham School scheduled a fifty-year reunion for 1967 graduates in June 2017. David Mould did not attend.

****,

David H. Mould, Professor Emeritus of Media Arts and Studies at Ohio University, worked as a newspaper and TV journalist in the UK before moving to the US for graduate school in 1978. He retired in 2010 after a thirty-year career as a faculty member and administrator, and he now calls himself an “itinerant academic worker.” He serves as a consultant for UNICEF, designing and developing training programs and research projects on communication for development; he has also worked for the US Department of State, USAID, UNESCO and other agencies, mostly in Asia and Southern Africa.

David’s first book on travel, history and culture, Postcards from Stanland: Journeys in Central Asia, was published in 2016 by the Ohio University Press; his second, Monsoon Postcards: Indian Ocean Journeys, will be out in early 2019. You can read his travel blogs on Facebook and at www.davidhmould.com.

*****

For anyone wishing to tour present-day Caterham, there is a video on Vimeo.

Don’t forget to follow us on Facebook and to clap on Medium.

*****

True stories. Honestly.

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave