“Good writing is honest writing, but honesty is hard to come by.”

BROAD STREET: Julie, thanks for talking with us! Let’s start with perhaps the toughest question — how do you define “truth”? Is it different from “honesty,” and if so, why?

Anderson: Hmm . . . I’m not quite sure how to answer these questions, but a story comes to mind. I once attended a conference on memoir writing and one of the people leading the conference — a famous writer — gave a talk about how, when she was young, she’d been commissioned to write a magazine article on kayaking along a French river. As it turned out, she arrived too late in the season to kayak, so she took a hike by the banks of the river instead. The editors hated the piece and told her to “sex it up,” hinting that she make up something more exciting. She then rewrote the piece to include a kayaking journey and a playful water fight with flirtatious Italian men. The editors loved her “revision” and published it immediately. She told this story to make the point that you can change the facts as long as you’re “emotionally true” to the experience.

It sounded like good advice, and she was famous after all, but, honestly, I couldn’t disagree more. I really wish I could have agreed — I’ve traveled widely and could make up some really wonderful stories that might capture the spirit of a people or place. But then, is that a true story?

I feel it’s critically important to represent the truth as accurately as possible. If the facts don’t fit your story, then it’s the story that needs to change.

If you say it’s true, in my opinion you shouldn’t make up events or people. Especially in this day and age, when so many alleged authorities play fast and loose with the truth (or just blatantly lie in the face of provable facts), I feel it’s critically important to represent the truth as accurately as possible. If the facts don’t fit your story, then it’s the story that needs to change.

That said, I’ve read that the more you recall a memory, the more you change it; those who remember an event the most accurately are those who hardly recall it at all. For a writer of nonfiction, that’s clearly a problem. Whenever possible, I refer to my notes and journals, and I consult outside sources if available. Then I do my best to present events as they happened, even if I know that I won’t get them 100 percent right.

What role does this drive toward honesty play in your writing–your nonfiction, certainly, but also any other genre in which you work?

Good writing is honest writing, but honesty is hard to come by.. There are so many layers to personhood, so many striations and gradations that make up who we are, and each one bears its own truths and deceptions. The most honest writing I do embraces these complexities and contradictions; it doesn’t reduce people — or the world — into something easy to categorize or contain.

Usually, the harder something is to say and the more I have to struggle to write it, the more “honest” the writing is. In the end, though, I’m not sure anything I write is truly honest. It’s a good-faith gesture in that direction, at best.

There are many very specific and carefully researched facts in your essay, “It Cannot Be Conceived.” What drives your quest for truth as you evaluate facts and have to fill in some blanks — emotions felt by people you’re writing about?

There are, as you say, always blanks to fill in when you’re writing nonfiction. It’s impossible to know exactly what another person is feeling; they may not even know themselves. You do your best to empathize, to feel what they must have felt in that situation, but you can never be absolutely sure you’re getting it right.

Dialogue is hard, too; you just have to hope readers understand that you’re paraphrasing. There may be a few people who remember dialogue verbatim (James Boswell comes to mind), but I’m pretty sure most of us don’t. So you do your best. That might seem like overly simplistic advice, but intention and effort matter. In the end, that may be all we have: an intention to be “true” to a story, and a willingness to put in the hard work to tell it as accurately as we can.

How do you choose your subjects — that is, how do you determine something must be written about? The decision to write about an experience that shook your sense of self (a ME-moir) might seem organic, but how do you figure out what else needs to be recorded?

The less I understand my own motivations for writing about a topic, the more worthwhile the topic is. I write to explain myself to myself. In the case of “It Cannot Be Conceived,” I was fascinated by the foreigners who lived through the Chinese Cultural Revolution, though I didn’t initially understand why they intrigued me so much. In the course of writing the essay, it hit me that it was their idealism that drew me; they were so wonderfully idealistic, and yet so catastrophically misguided, so woefully wrong in their perception of Mao. It makes me wonder about my own values and beliefs. What am I possibly wrong about?

I also try to think about my audience: is anyone else going to be interested in this topic? In that sense, writing about China was an easy choice for me. China’s a place most of us in the West still don’t know enough about and it’s interesting — certainly worth someone’s time to read about.

Perhaps you’d like to say a couple words about what your Ph.D. work entailed and how you put so many elements together to create one interpretation of truth among apparently very different disciplines.

My Ph.D. is in comparative literature: classical Chinese poetry in comparison with ancient Greek and Roman lyric poetry. I loved learning about the ancient world, but I was eager to learn about the modern one, too.

I started researching modern China because I had an idea for a novel based on foreigners who lived through the Cultural Revolution. In addition to the novel, though, it occurred to me that it would be interesting to write a nonfiction piece juxtaposing my own life in China in the early nineties with the lives of this older generation of foreigners.

The less I understand my own motivations for writing about a topic, the more worthwhile the topic is.

Whether in scholarship or in essays and fiction for more general readers, how do you select the details that will connect with readers? You might want to think a bit about your autobiographical piece for Writers on the Job,“ Internship at Tiffany’s” — delving back into an experience to which some readers will bring preconceived ideas.

I always think about Janet Burroway’s advice from her wonderful book Writing Fiction. She says that a detail needs to be concrete and significant, by which she means that a detail should appeal to at least one of the five senses and should convey an idea or judgment that readers can infer for themselves.

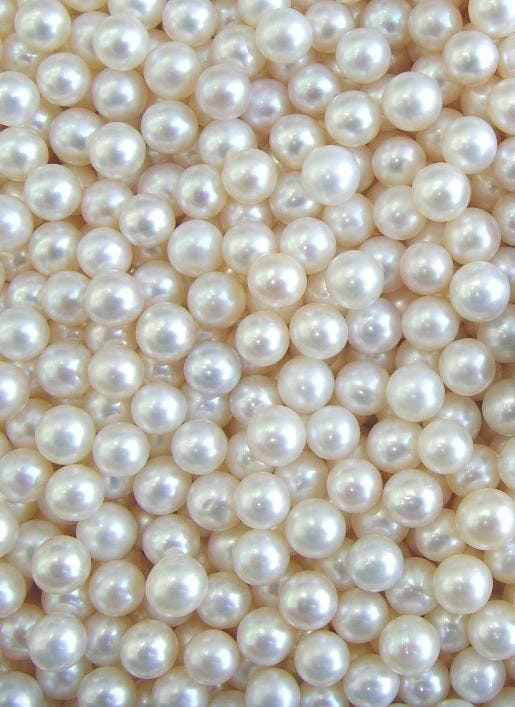

Also, a good detail should pertain to the theme of a piece, and I especially like details that are funny. For example, in “Internship at Tiffany’s,” I described putting pearl necklaces worth half a million dollars between my teeth so I could determine if they were real. Apparently, that’s how you test for authenticity: if you rub a pearl against your teeth and it feels grainy, then it’s genuine.

I find this an appealing detail because it’s so outlandish and absurd. It also speaks to my younger self’s slight rebelliousness as well as to my boredom sitting around an office all day with these crazy expensive pieces of jewelry.

I’m not sure what readers will take out of it, but that’s the pleasure of a good detail: it lets readers derive their own meaning.

Now let’s think a bit about your early days. When you were a struggling/dreaming new writer, what gave you inspiration and kept you going? Did you face a lot of rejection, and if so, how did you process it and move forward?

I’ve faced a lot of rejection and still do. I wish I were more immune to it. I read a while back about something called “rejection therapy,” where you practice getting turned down for weird stuff like asking strangers for a dollar or requesting doughnuts made in interlocking circles like the Olympic symbol. That “therapy” seems so great if it works, but then again, I’m already practicing my own form of rejection therapy by sending my work out, so why wander the streets asking people for a buck?

In the end, what keeps me writing is that I simply enjoy it. For me, writing is a form of meditation where what matters isn’t the product, but the process. I also take satisfaction in watching my skills as a writer grow and develop. But I’m not going to lie; rejection is hard and it doesn’t get easier over time. I’ve just gotten more used to it.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers–in any form?

Try going into accounting! Okay, seriously, the fact of the matter is that no matter how successful you are, there’s always going to be someone more successful, so if you’re writing for acclaim and glory, forget about it. But if you write because you find it magical, meditative, subversive, life-affirming, and/or occasionally joyful, then it’s worth it. Whether you’re creating a nonfiction essay, story, novel, or poem, it doesn’t really matter; it’s the act of creation that counts. Just don’t be attached to monetary rewards or great acclaim!

True stories, honestly.