“In all my art history classes, I had never read about a Western sculptor who had moved to China and let that culture influence his or her work. I wanted to be the first sculptor to do it.…”

Broad Street’s interview with international sculptor Daniel M. Krause appeared in our “Hunt, Gather” themed issue in spring 2015. Now, with a handful of the Chinese terra-cotta warriors making a world tour in 2017, it’s a good time to check in with Daniel, who was one of the first U.S. artists to study and draw inspiration from them.

Here you can read his take on the warriors, expat life in China in the 1980s and thereafter, import-export businesses by which he survived and fed his art, newshounding during the revolt at Tiananmen Square, carrying the Olympic torch, and much, much more, in this lively interview with longtime friend and Broad Street editorial director Susann Cokal — now with added photographs and links to further features.

This interview is also available in a photo-friendly version on Medium.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — —

“The Jaw Drops Each Time”: interview with Daniel M. Krause, Sculptor.

Interviewed by Susann Cokal.

Daniel M. Krause is an adventurer in the wilds of art. After growing up in the Chicago area and in Southern California, he studied microbiology and sculpture at the University of California in San Diego (UCSD), where he worked as an apprentice to sculptor Italo Scanga. Upon completing his B.A., he took off for China and other parts of Asia, eventually earning a Master’s of Fine Arts at Guangzhou’s Academy of Fine Art.

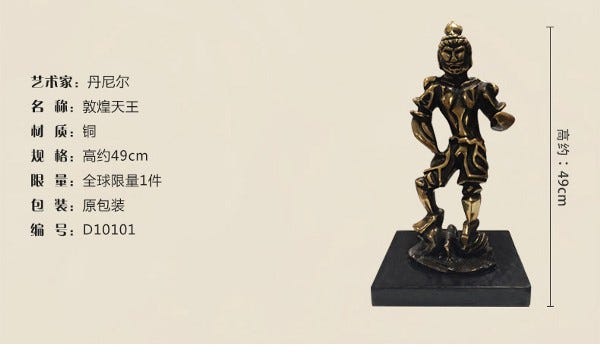

Daniel’s bronze sculptures have been displayed in dozens of galleries in Guangzhou and Beijing, Hong Kong, and New York, and they are permanently installed at the Church of Scientology flagship center in Clearwater, Florida. He has had many corporate and private clients, being especially known for large bronze renderings of the human form. He was even chosen to carry the Olympic torch on its way to the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.

Now (2015) he’s at a crossroads, planning a partial return to the U.S. He and Cokal conducted this interview via email while Daniel was traveling among remote pockets of rural China and on to Vienna for a grand costume ball with the love of his life, Alex Voss.

— — — — — — — — —

Broad Street: You went to China very young, in 1987. How did you have the guts to do such a thing, especially when China hadn’t been opened to the U.S. for very long? And what were you planning to do?

Krause: I wanted to learn Chinese and earn an MFA at the Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts, in China’s oldest capital. In all my art history classes, I had never read about a Western sculptor who had moved to China and let that culture influence his or her work. I wanted to be the first sculptor to do it. I had a degree in microbiology, but art was much more compelling to me. And I’d discovered I hate the smell of laboratories and hospitals.

My major motivation was to study the terra-cotta warriors in the Emperor’s tomb in Xi’an, discovered in 1974. I think those warriors are by far the most interesting installation in the world. There are more than eight thousand figures, and each one is unique. I’ve gone to see them eight times, and they are a total jaw-drop each time.

I’ve watched workers unbury them. Some of the ones on display are restored and assembled; others are still half half-buried and have parts missing. I like the ones that are not completely re-assembled.

There is a story that goes with each figure. I think of the sculptor and his own army of workers that made these warriors around 210 B.C.E. No other artistic event in the history of mankind comes close to this type of project. These burial figures are to sculpture what the Pyramids are to architecture.

***

How did you survive financially in those early years?

A mixture of teaching, government work, entrepreneurship, and whatever else I could get. At first I taught Shakespeare to seniors in the high school attached to the People’s University in Beijing. They paid me 300 rmb a month, around $35 — which was more than triple what the other teachers were getting.

When I started my MFA studies in 1988, I survived as a part-time English teacher at Sun Yat Sen University. Then on June 4, 1989, came the Tiananmen Square event, and for a few months I was an interpreter and newshound for the London Times and BBC television news. I also taught English in Japan for nine months.

Eventually the U.S. Consulate in Guangzhou created a position for me in the Cultural and Press Department so I could return to my studies. So in 1992 I began working part-time at the U.S. State Department. I’d always wanted to do something for my country but was not interested in the armed forces. Working for the U.S. Consulate was my way of giving time to my country.… I also needed the money to help pay off my student loans.

In the end, around 1994, a classmate from UCSD and I began designing and manufacturing houseware accessoriess for export to Pier One and other American companies. We made candleholders, photo frames, mirrors, and nesting tables. We were the only Western people with a booth at the Canton Trade Show, China’s largest trade show at the time. It was Westerners selling to other Westerners …

During all this time, my ultimate plan was to finish the MFA in China and come back to L.A. and work in Hollywood doing special effects. I’ve always loved science fiction movies, and back then I still had a hard time seeing fine arts as a way of making a living.

***

Why did you stay in China rather than returning to L.A. as planned, and how did you fit in once you were finished with the university?

By the time I finished the MFA, I inhabited my own sort of space, half in a Western expat group of businessmen and half in a group of Chinese artists and locals from different walks of life. I stayed in China to keep life interesting.

Plus, I dreaded driving in Los Angeles car traffic each day to work. And living in China makes it very easy to get onto an airplane and be on a South East Asian tropical island within a few hours.

So I’m an artist.

My present studio is in a very large Chinese art community east of 798. That area, 798, is the largest and main art district in Beijing; anybody who knows about the Chinese art scene knows 798.

The community is nice because it is built in a way that artists can live there and work affordably.

But 798 is right next to a village where the contrast between how we live in our apartments and how a Chinese worker lives is night and day.

Politically I am off to the side and enjoy developing my artwork quietly. I’m a Democrat and never joined the Communist party.

I do not feel I’ve succeeded financially yet. I still have two sons to put through college, and it is time to get a new business plan to make large outdoor sculptures. I’m working on that now.

Or maybe it’s time to combine microbiology and sculpture … Biotech Art, Inc.?

***

You make some huge metal pieces, many of them on commission. Where do you get the materials for making work on such vast scale? And where do you put them together?

I work with Chinese foundries and sculpture fabricators. With all of China’s industrial development, public sculptures have multiplied all over the country, and there are many factories that specialize in helping sculptors enlarge their work. We assemble them both at the factory and on site, depending on how large they are.

I have become a master at logistics and moving large objects around the world with containers and ships. Each time I make a sculpture, there are a lot of logistics for moving it from the foundry, whether to a gallery, a collector’s residence, or a museum.

Every year I seem to find myself on a truck with a big sculpture in the back.

(Watch a Chinese video of Daniel welding, climbing, and otherwise creating some of his most massive work here.)

***

Can you say something about the works you’ve done on commission? How is working to a patron’s expectations different from doing art “for yourself”?

I have worked on three large projects with clients. The artist and the client need to listen carefully and communicate with each other at each stage of the creative process. The trick sometimes is to educate the client and bring the aesthetic into the twenty-first century.

My largest commission has been for Scientology’s flagship building’s atrium in Clearwater, Florida: my Sistine Chapel of the Twenty-first Century. It took two years and I made forty-eight larger-than-life-sized figures representing the philosophy of Scientology.

They were featured in the Scientology commercial during the Superbowl in 2015 (watch it through our website here).

***

You just bought land in Taos, New Mexico, which is known for its artists’ colony, and you’re building your own studio there. What is bringing you back to the U.S. — and to New Mexico in particular?

After working my entire adult life in China, it is time to make life interesting again — complicate it, maybe — and move a little closer to my parents, my siblings, their children, and my own children, who have settled on the West Coast.

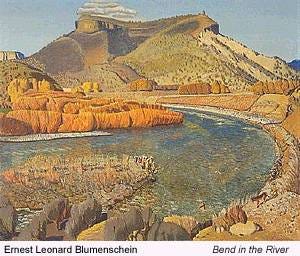

It has always been a dream of mine to have an art studio in Taos, New Mexico, because it is one of America’s oldest art communities. Georgia O’Keeffe started working in northern New Mexico in 1929, for example. The combination of Spaniards, Indians, Europeans, and “other” Americans, plus the scenery, has turned Taos into a very special place.

My studio will be off the grid, on a large plateau without many people. There are around ten neighbors, each more than two hundred yards away in each direction.

I will always keep China in my life, but I’m going to start spending three or four months of the year in Taos. As of now I do not know where I will be the other eight months of the year — perhaps in California, Europe, or Asia.

Recently I have found my soulmate, Alex, and support her endeavors too. We will see where life brings us next.

— — — — — — — — — —

Like what you’ve read here? Then please press the Medium’s hand to applaud for this piece and help others find it. And be sure to visit us at broadstreetonline.org for more features and treats.

Featured photo: Daniel with The Matador, steel, 2017.

True stories. Honestly.