From Our Pages: “Dale Flynn’s Blood,” memoir by D. J. Lee.

by broadstreetmag on Apr 27, 2018 • 5:42 pm No CommentsTrouble next door.

“I pushed away and we stood in the soft wet dirt of the shoulder, staring at one another. Suddenly, he lunged forward …”

D. J. Lee’s searing memoir of bullying, aspiration, and teenaged hormones appeared in BROAD STREET’s “Bedeviled” issue in winter/spring 2015. It has been praised for its gritty portrayal of anger and confusion in the 1960s — an era when a house on a cul-de-sac and a trip to Disneyland represented elevation in social status, and a struggling father might try to impress his family with an easily stolen heirloom. The essay was recognized with a Special Mention in the Pushcart Prize series.

We are proud to present the essay in its entirety, specially formatted for the web. Click here to go immediately to the full essay, or begin with the excerpt below.

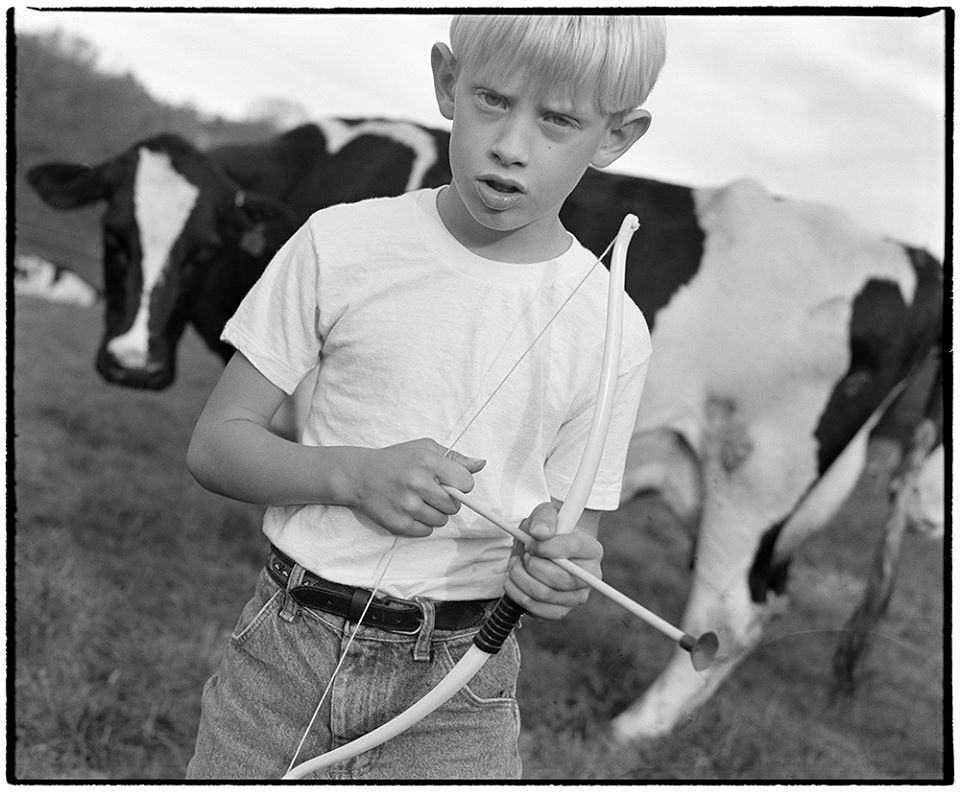

Photo: “Todd,” by Chad Hunt, 1998.

Dale Flynn had a vendetta against me. Every day in fifth grade, he chased me from the bus stop on 208th Street to the cul-de-sac where we lived, a distance of two blocks. He caught me by the shoulder, whirled me around, pushed me to the ground, and punched me. I screamed, he let go, and I bolted for home.

This was the 1960s. The cul-de-sac was in a gritty suburb in Seattle, a place of strip malls, grunge bands, and big industrial buildings. The mothers stayed home while the fathers worked low-income jobs. One sold shoes. One was a Baptist preacher. One was killed in the Vietnam war. Dale’s father, old Mr. Flynn, a beefy man with a crew cut, didn’t do anything. My father complained, “He’s a cheater, he’s not crippled,” because Mr. Flynn was on government disability for a shoulder injury. Our backyard faced the Flynns’, and we’d see him working on a fence as if he were in perfect health.

One day in the spring, when Dale chased me out of the bus, I threw my body against his and gouged him in the face. His skin tore like tracing paper. Blood seeped from his cheeks and spread onto my white blouse.

I pushed away and we stood in the soft wet dirt of the shoulder, staring at one another. Suddenly, he lunged forward and grabbed the hood of my parka. I let it slide off my shoulders and ran.

I wouldn’t have to worry about Dale anymore, I thought, but as I turned into the cul-de-sac, a new concern set in. The parka was supposed to last me through the next few winters. My parents didn’t have money to buy a new one every year.

At home, I washed Dale’s blood off my blouse as best I could and shoved it in a corner of my bedroom. I never did get the stain out. I looked for my coat along the street the next few days. I didn’t find it, but my parents didn’t seem to notice. I thought I was safe until one day, as I walked out the door into a thick Seattle rain, my father asked about it.

“Dale Flynn took it,” I said.

“Goddammit,” he said. His neck grew thready lines and he stomped around. Normally when his temper flared, he spanked us. But he didn’t touch me that day. “Get in the car,” he said, and drove to school, where he talked to the principal: “My daughter should be able to walk home from school without getting beat up. It’s your responsibility to end it.”

The principal, a tall man with a distracted look in his eyes, said, “I’ll do what I can.”

Dale stopped chasing me for a few weeks, and when he started again, I didn’t tell my father. I resigned myself to the fact that nothing ever changed. And then something did. Maybe because I was older and stronger, I was able to outrun Dale most of the time. When he did catch me, he tackled me and pinned me to the ground as usual, but instead of punching me, he let his face hover a few inches above mine, our eyes locked.

I began seeing him in a close-up way all the time. When he was in a desk on the other side of the classroom, I noticed his velvety hair and his soft flannel shirts. Sometimes I let him catch me. When he lay on top of me, he was light, as if his bones were partly hollow, like honeycomb….

“Sexuality tingled in every pore and my sense of duty lay dormant…. Some part of me believed that learning to fight my way through life was as thrilling as it got.”

… Two years later, the diary I kept was a gift from my mother. It was a small book with a lock and key. I wrote about the fights she and I had—not unusual for someone my age—and my father’s efforts to keep me under control. He took me fishing on Lake Stevens and to the arboretum ,where I learned to name local plants.

I described the day my father installed a tetherball pole in the backyard. He cemented it next to the ladder leading to my brothers’ treehouse. In the evenings, instead of watching T.V., he volleyed the ball with me while my brothers climbed trees above us. Usually, after I beat him several times, he went inside and I joined my brothers in the trees, but I couldn’t get into their make-believe world of guns and battles the way I used to. I longed for a life beyond family.

I wrote in my diary about my job. A woman who tended bar on Aurora Avenue had hired me to babysit her two daughters on weekends. Her closet was full of lamé blouses, rhinestone belts, and fishnet stockings. After I put the girls to bed, I paraded around the house in her clothes. On paydays, I walked straight to Fred Meyer to buy imitation versions of her wardrobe, like the mushroom-brown suede purse with the fringy bottom.

Once, I wrote about Dale Flynn. I had been at a party where some kid’s lenient parents had bought kegs of Budweiser and we gathered in a wooded area to drink, smoke pot, and make out. I had just peed in the bushes and was pulling up my jeans when there was Dale, slouching against a tree.

Perhaps we would have started talking if one of his brothers hadn’t have shown up.

“You have a nice ass,” Dale said as I walked away.

I also wrote about the time I wiggled into a denim minidress, combed out my wavy hair, and slung my fringed purse over my shoulder, where it swished against my bare leg. When my mother saw me, she told me I had to stay home and babysit my brothers. “No,” I said. “I’m going out with my friends.”

My father, who was sitting in the rocker, wadded his newspaper. “Mind your mother,” he said.

But I couldn’t obey her. Sexuality tingled in every pore and my sense of duty lay dormant. As I walked past, my father got up and stepped in front of me. “You’re not hanging out with those good-for-nothings.” I tried to scoot around him, and he grabbed my arms to hold me back. I screamed, “No! No! No!”

This was what I was saying out loud. Inside, I was saying, You’re not going to stop me. Even when he threw his arm up to backhand me across the face.

I wrenched free and scuttled behind the sofa, crouching. I became aware of my mother banging pans and of my brothers’ voices in the kitchen. My father was scrambling around the sofa when my mother’s voice broke through: “Leave her alone!” I fled to my room and hid in the closet and cried.

After a while, my father opened the closet door. “Come out now, Sis.” He said this in a firm voice, but it was soft around the edges. The name “Sis” was a term of affection. It signaled my role as big sister to my brothers. It was also his way of apologizing and telling me he would protect me with the same fierceness with which he punished me. I understood that he was imparting skills, ways of fighting. Some part of me believed that learning to fight my way through life was as thrilling as it got.

“Quit feeling sorry for yourself,” he said. I crept out of the closet. “We love you. We want what’s best. That’s all.” I limped to the kitchen where my mother held a pan of cookies at the counter. She didn’t look at me. My brothers swung G.I. Joe figures to and fro in the air to the rhythm of my sobs.

———-

To finish reading the essay, click here.

———-

D. J. Lee’s creative work has been featured or is forthcoming in Narrative, The Montreal Review, Vela, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. The author of three books of literary history and editor of three critical collections focusing on the nineteenth century, she is currently completing two memoirs: one about the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness of Idaho and Montana, one about motherhood in the Arctic. She blogs regularly at http://www.debbiejlee.com.

D. J. Lee’s creative work has been featured or is forthcoming in Narrative, The Montreal Review, Vela, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. The author of three books of literary history and editor of three critical collections focusing on the nineteenth century, she is currently completing two memoirs: one about the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness of Idaho and Montana, one about motherhood in the Arctic. She blogs regularly at http://www.debbiejlee.com.

True stories. Honestly.

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave