“The best any of us can do is narrow the inevitable gaps between our best words and the truths they aim to capture and communicate.”

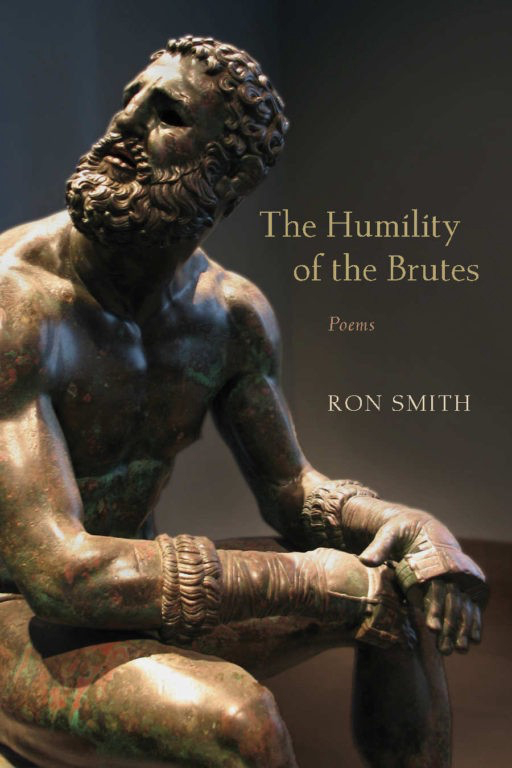

It’s been a few short months since Ron Smith, former Poet Laureate of Virginia and contributor to our “Maps & Legends” issue, published his fourth book, The Humility of the Brutes, with LSU Press. It’s a beautiful collection touching on everything from love to travel, and it’s been earning raves from the likes of David Kirby, who wrote, “These poems grab you the way a wrestler does…. They leave you feeling as though you’ve just been in an awful wreck but that something big is coming your way, something better.”

We’re proud to say that six of the poems included made their debut in Broad Street’s “Maps & Legends” issue. And that when we asked Ron to discuss the book in more detail — the poems themselves, the process of writing them, and how a poet puts a book together like a record album — Ron agreed. He and Susann Cokal had a chat about the book and the life in early May 2018.

Ron recently served as the Poet Laureate of Virginia, and he is the Writer-in-Residence at St. Christopher’s School in Richmond. His work has been published in numerous major literary journals, and he is the author of three other books: Running Again in Hollywood Cemetery, Moon Road, andIts Ghostly Workshop.

We’re happy to present Ron’s poems from Broad Street as broadsides suitable for printing and framing: “John Smith in Virginia,” “After Church,” “Angelus: Chesapeake Bay,” “Volterra,” and “1911.”

See other great poems from Broad Street under the “Share This Poem” heading.

This interview is also available on Medium, in slightly different format.

****************************************************************

Broad Street: First of all, Ron, congratulations on publishing another wonderful collection! And for the great reviews and attention it’s been getting — we’re all very excited for you, and not just because some of the poems first appeared in our pages.

Ron Smith: Thank you, Susann.

Broad Street:We already have a great Truth Teller Spotlight interview from you, in which you discuss what truth means to you and how you work that sense of emotional authenticity into your poems. Now I want to ask if there’s a way in which truthfulness becomes elastic and stretches in different directions — for example, when you’re writing through the eyes and voice of a historical personage, as opposed to a tight focus on your own life?

Ron Smith: It is, I believe, literally a matter of life and death for us to believe that objective truth is significantly real.

However, that does not mean that truth is not often slippery — or stretchy. Uncovering even simple truths can be hard work. And telling the truth can be even harder work.

As I say, “All slopes are slippery slopes. We have to get used to it.”

Persona poems enter into the minds of people other than the poet — an act unfortunately impossible outside of art. Earnest persona poems do their best to present the states of mind and the thinking of the other. It goes without saying that the attempt is likely to fail. We do our best to come at least close to the truth. The best any of us can do is narrow the inevitable gaps between our best words and the truths they aim to capture and communicate.

(There are other reasons to write persona poems, of course. For instance, I think there is always at least a small element of parody in a persona poem.)

Broad Street: For anyone who works in short forms, there’s the question of how to put a collection together — how to choose the poems that belong together between the covers, plus the order in which they should come. I suppose we could call this the “record album” question — it’s certainly one we think about here at Broad Street when we put together our themed issues, considering pace and mood and how the different bits of writing and art will converse with each other and become more than the sum of their parts. So the next few questions are about that topic.

Here’s the big question: How doyou decide on an order for the poems? How do you see the collection as telling a bigger story (or is that question not relevant for you)?

Ron Smith: When it comes to structure, when it comes to overall form, I begin by working intuitively. This is true within the individual poem and within the collection of poems. I want the poem or the book to tell me what it needs. I want my wise subconscious mind to ignore my arrogant conscious mind and discover something new. Or something archetypally old. I fear that if I work consciously, merely rationally, I will impose a predictable order. Some kind of obvious mere thinking. So that’s how I proceed. When it works, fine. I can sense when I’m done. Good. Send it.

But … Often, I get stuck. Too often, my intuition doesn’t finish the job; it doesn’t produce totally satisfying results. Often, the intuitive only takes me to the edge of a solution. Then I have to start counting syllables and lines and stanzas and making charts and diagrams. That’s when I rationalize and make conscious two things: first, what I have been doing, second, what I now suppose I ought to be doing.

“Often, the intuitive only takes me to the edge of a solution.”

In The Humility of the Brutes, I discovered a sort of wave pattern. I saw that was happening, so I made it a conscious element of design.

Broad Street: Do you expect readers to go through the book cover to cover, or do you think they’ll look at the Contents page and decide to skip around based on the titles of the works? Or even just leaf through the book and see where they land, almost like a process of divination?

Ron Smith: I always hope that my best readers will be so hooked by the first few pages that they will read straight through from first page to last. But I know how people tend to read, so I also like the idea that in skipping around readers can create their own eccentric structures while nevertheless yielding themselves to the effects created by, if not the entire collection’s beginning/middle/end, then at least each poem’s beginning/middle/end.

And I hope people will read some poems over and over, that they’ll do at least as much rereading as first reading. A worthy poem is like a good song. You don’t hear it once and say, OK, got that. You want to savor it again and again.

“I like the idea that in skipping around readers can create their own eccentric structures.”

Broad Street: Is there an ideal place in which someone should read this book … in bed at night, on a garden bench, on a lonely beach? Do you imagine someone, say, drinking wine with your words, the way François Rabelais recommended?

Ron Smith: When I see people reading a book in public — at a doctor’s office or in an airport — I almost always ask them what they are reading and how they like it. I hope people will read my book the way I read books of poems: everywhere and over and over. A glass of wine? Sure. Four glasses of wine? Why not?

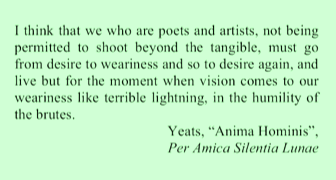

Broad Street: The Humility of the Brutes is a great title, and it comes from a bit of Yeats you quote in the book’s epigraph. How did you hit upon that quotation, and how did you decide its concluding words would be the title for your collection?

Ron Smith: I read night and day, every day, all sorts of stuff. I skip from book to book, newspaper to magazine to journal, from blog to blog.

I don’t remember precisely when I came across this rather obscure Yeats quotation — but I love Yeats and I was fiddling with some pleasurable research.

I do know that I stumbled on the Yeats after I had begun daily to spread out the book’s poems on the floor of the den and on the dining room table. I was just walking around, looking at the poems, trying to see how they talked to one another, how I might revise one to fit with a group, that sort of thing. When I came across the Yeats quotation, I realized what I had been groping toward — and the image on the book cover flashed into my mind. It’s a photo I took a few years ago in Rome of my favorite statue, an exhausted, tough, humble, dignified boxer after a hard fight.

At that moment, my intentions became conscious, and I began grouping and sequencing (and in some cases revising) the poems in the book. Yeats’s notion that we go from desire to weariness and so to desire again — or from insight to bafflement and eventually to insight again — created the wave pattern that I see in the book. The increasing then lessening intensity. The delicacy giving way to harshness, then back to delicacy again.

“I want the whole world in my books — including the world I encounter in my reading.”

Broad Street: The range of subject and voice in this volume is impressive. You hop from Big Historical Figures (John Keats, Thomas Jefferson, Popes Clement VII and Leo X, some Confederate dead) to rather frolicsome poems about the Baseball Hall of Fame, into intensely personal poems about your own life, church, and taking a young boy on a melancholy tour of Confederacy-related sites in Richmond, Virginia (your adopted home town). Can you say something about the scope you wanted the book to have, perhaps the ideal reader or readers with whom it will resonate?

Ron Smith: As I finished my previous book, Its Ghostly Workshop, I realized that I wanted it to bristle with persons and personages, sort of like a big, complicated novel, maybe something by Fielding. Even the dedications help to multiply the characters in the book.

Like Whitman, I want to include everything — actually, more than Whitman, who kept himself almost exclusively restricted to North America.

I want the whole world in my books — including the world I encounter in my reading. I want a poetry less elitist than T.S. Eliot, but much more literate and literary than W. C. Williams, if that makes any sense.

Ideal reader? Someone with curiosity about nearly everything and an ear for good language. I want readers who aren’t irritated when a piece of writing sends them to Google. Someone who knows that writing history is partly an art and that all art has a history. Someone who is willing to believe that you can actually live most intensely and vividly in the present moment by knowing more about the past.

“I want the poetry of the twenty-first century to do everything prose can do…. I want as much of human experience between the covers as I can manage.”

Broad Street: Many of these poems are grounded in a particular place — all over Virginia, plus Russia, Italy, and more. How important a part of your process is travel? How would you tell a young poet to engage with place in poetry — perhaps especially if that person weren’t able to travel?

Ron Smith: My early work (like most poets’) was autobiographical — though not merely “factual,” not journalistically so. My more recent work has become historical and ekphrastic; travel helps me expand my range of reference.

I want the poetry of the twenty-first century to do everything prose can do, including providing travel guides and memoirs and adventure stories, though those functions are generally secondary in poetry. Too many poets narrow themselves down to mundane observations or linguistic psychodrama. I want quiet observation and cavorting mind-words in my poems, too, but I want the reader to feel he or she is in not only a mind or a memory but also a body, a body moving through cities and suburbs and countryside, a body always in this century, in the here and now, but a body that can, somehow, be, say, also in the eighteenth century.

I want as much of human experience between the covers as I can manage.

“I want my wise subconscious mind to ignore my arrogant conscious mind and discover something new. Or something archetypally old.”

Broad Street: What do you do if you’re stumped for a topic or for the style in which to relay the topic?

Ron Smith: I don’t get stumped for a style or form much anymore, because I let the content create the form — and there’s so much content I want to wrangle into form.

Or, rather, I do get stumped for a while, but I’m more patient with revision and failure than I used to be. Now, I love the moment when I throw out a form I had been developing through many drafts, the moment when I start completely over because now see that the poem needs cacophony or short lines or a preposterous shift in tone or a wavy look on the page or whatever.

Topics? The humble city of Richmond has a couple of million poems just waiting to be written! And what about the city of Rome? A couple of trillion, I guess. Parenthood as a subject has not yet been exhausted. Nor illness, acute or chronic. Nor memories of youthful health and energy.

When I demonstrated to myself that — even though poets have been writing about the city of Rome for over two thousand years — when I saw I could actually produce poems that were fresh and maybe even original about Rome, of all places — that’s the moment when my confidence soared. (Here’s hoping it stays high. Knock on wood.)

Broad Street: Were there any poems you loved that you had to cull because they didn’t seem to fit with the rest? If so, what have you done with those poems — are they perhaps in separate files, to become parts of one or more future collections you already have in mind?

Ron Smith: That’s always the case. A few of the poems in my recent books were in the first drafts of my first or second book. But they didn’t seem comfortable (or functional) there. So they had to wait. Some are still waiting.

“I’m more patient with revision and failure than I used to be. Now, I love the moment when I throw out a form I had been developing through many drafts, the moment when I start completely over.”

Broad Street: There’s plenty of wit in poems that take on weighty subjects — for example, “Bronze Boxer, first century B.C.” reads like an epic moment cataloguing the battered body, then moves to a sort of “You should see the other guy” at the end. How do you see moments of perhaps sardonic humor playing off heavy emotional moments in your work? Would you unpack that aspect of your aesthetic for your readers?

Ron Smith: John Frederick Nims said, “A sense of humor is a sense of proportion.” For all the intensity that poetry encourages, I don’t want my books to lose their common sense, their sense of proportion. Also, when I am reading a new poem, when I am writing a new poem, I’m not thinking in terms of meaning, really. I am thinking in terms of effect. What does this image or this line break or this rhyme do to the reader? Humor is one device that helps me surprise good readers, to shift their focus. It’s also an indispensible aspect of a healthy life. Everybody needs at least one good laugh every day.

Broad Street: If I were to say this book addresses one major subject — and perhaps I shouldn’t pin down just one — I’d call it a handbook to ideas of masculinity, from the physical to the intellectual, historical to modern. How right or wrong would this assessment be? Masculinity, patriarchy, and the whole shebang are really under a spotlight in this country now; what would you, ideally, like to contribute to that conversation?

Ron Smith: I think the book is about many, many things. BUT if I had to sum up its central focus, I’d say you are right on the money — though any personal/public correspondence is purely accidental.

Some of the poems in Brutes have taken me decades to write. And it’s certainly taken me decades to see Southern males — especially myself — with anything like acceptable clarity. It’s an ongoing project.

Here’s hoping we men can be more effectively human and stop trying so hard to be merely manly.

Broad Street: Hear, hear! And thank you again for another fascinating interview!

******************************************************************

Like what you’ve read here? Then please remember to follow Broad Street on Facebook and our website.

True stories, honestly.