“Over the years I have discovered that they are sneaky, nomadic little creeps.”

From “Rivals & Players,” our Winter 2019 issue.

The Museum of Teeth

By Emily Woodworth

In the drawer beside her sock drawer, my mom keeps a small plastic bag full of baby teeth. Actually, make that two bags. One holds my teeth and the other holds my brother’s, plus one small white rock. Nathan made the fatal mistake of losing a tooth while playing T-ball and had to find a geological replacement. But mine are a complete set, which I find oddly satisfying.

It was only after I had lost every single one that my mom showed me the Baggie. It was like some strange exchange — “The tooth fairy is dead, so here are the teeth I bought from under your pillow.”

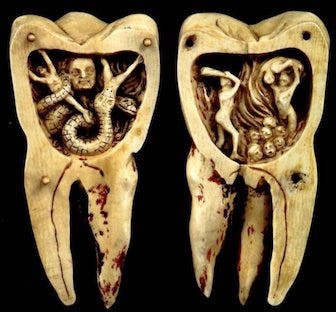

The first time I saw them, I couldn’t wait to take them out of the bag and reconstruct my mouth from a few years back. It felt like being reunited with old friends. I stroked the smooth white planes and rough blood-encrusted undersides where the teeth had attached to my gums, remembering when these impossibly small items were a part of me. I knew exactly where each little molar went, how they all fit together. They were like fossilized remains of a past Emily; an archaeological record of who I had been. I still get them out sometimes, just to remind myself of who I used to be.

Onaverage, I don’t go more than fifteen minutes without thinking about my teeth — the ones in my mouth right now, that is. You could say I’m obsessed with them. I love clacking them together. Clack, clack. It’s a beautiful sound. Perhaps it’s beautiful to me because it isn’t something I have always been able to do.

Among the dental difficulties I inherited from my ancestors is an open bite, courtesy of my Uncle Ed and whoever had the trait before him. My dad noticed one evening that I couldn’t bite off spaghetti like a normal person — I always used my bottom lip to push the noodles against my top teeth and clip them off. According to Dr. Everson, the family dentist, I was a “tongue-thruster.” I had never learned to swallow properly, pushing my tongue against my front teeth instead of the roof of my mouth, and had gradually forced my incisors into positions that were not optimal for eating.

“Clack, clack. It’s a beautiful sound.”

We went to the Brace Place to get this problem fixed. Dr. Quas and his daughter, Dr. Quas, were my caretakers. A cohort of dental techs took molds of my teeth in cement that always tasted like false grape no matter what flavor I chose. Soon my pearly whites were encumbered by metal brackets and wires that redefined mouth-pain. We went on a three-year journey together, and they were the only people I’ve found who were as obsessed with my teeth as I am.

Before I had braces I’d assumed teeth were stationary, set in their ways. Unless you hit yourself in the face with a bat, those suckers weren’t going anywhere. Over the years I have discovered that they are actually sneaky, nomadic little creeps. Ever since I’ve gotten my braces off I’ve had the strange sensation that my teeth are plotting to betray me. I can almost feel them planning their movements. It’s like they’re keeping a bag packed and waiting for an opportunity to move back to their original positions, to sabotage all of Dr. Quas and Dr. Quas’s work.

I have to be constantly vigilant to keep them in place. I once forgot my retainer when we were staying at a hotel overnight, and spent the whole next day worrying about how much they had moved. Sure enough, when I put the retainer on after we got home, it was much tighter than usual.

————————–

One thing I’ve noticed about teeth is that anything that happens to them feels much bigger from inside my mouth. My tongue exaggerates things. I noticed this phenomenon with the loss of my first tooth when I was five. It was my bottom right central incisor, the tooth in the very front. I wiggled it incessantly on the way to school that morning, and all through class, feeling it painfully give just a little bit more with each pass. My best friend, Becky, happened to be in the same situation, except hers was on the top right. We had chosen seats next to each other as a sort of support group. The whole class was waiting for the moment one of them would pop out — Becky and I would be the first kindergarteners to experience this rite of passage.

“My tongue exaggerates things.”

When we were given a play break, we rushed into the bathroom and took turns standing on the stool, looking in the mirror at how our perfect little teeth swayed this way and that. I tried to pull on mine, but my fingernails were trimmed short for piano and I couldn’t get a good grip on the slippery white surface.

Our teacher probably realized that until those teeth came out the entire class would be distracted, so she sent us to the secretary of the school, Ms. Callan, for a deft extraction. Apparently, Ms. Callan was the person to see about such matters because she had long fake fingernails that were perfect for popping out little teeth. We walked cautiously to the office, and Becky made me go first. Ms. Callan came out from behind her receptionist desk and crouched down to my level, pinstriped skirt and all. My jaw opened so wide it nearly unhinged. She reached inside. I gripped Becky’s hand hard, expecting an awful jab of pain, but I suddenly found myself staring at a small tooth resting in Ms. Callan’s hand, and I realized it was mine. A piece of me was resting in her palm and it hadn’t hurt one bit. I suppose it was also the first piece of me that my mom zipped up in her little Baggie.

My tongue spent the rest of the day exploring the strange new vacancy in my once-solid row of bottom teeth. The hole felt bigger than it could possibly be. The gum was sore and squishy. My tongue, in the habit of having a tooth to wiggle, kept hopping forward to research the blank chasm in my mouth. In my mind, I kept visualizing an abyss the size of the Grand Canyon.

I lost quite a few teeth to women with long fingernails. Ms. Callan dealt with a few more, and my piano teacher, Ms. Donna, handled at least three. I remember she helped me get rid of one particularly stubborn second molar on the right side and top of my mouth. When she finally got it, we were both surprised to see extra tendrils of tooth, which had been anchoring the outside front right corner into the gum, like a weird weed of some kind. This is my favorite tooth to look at in my mom’s plastic bag. It’s like my own little freak-show. I can imagine putting it in a glass case someday under lights, just to creep people out at dinner parties — This is my weird baby molar that grew a root. Just thought you would want to know. It’s a point of pride that I had such a strange thing clinging to my gum, wanting so badly to stay with me.

————————–

My grandma has a creative way of dealing with her teeth. For some reason my mom’s side of the family, excluding my mom, has a deep distrust of dentistry. So when my grandma realized her molar was cracking a couple of years ago she, of course, did not go to the dentist. Instead she bought a tube of Krazy Glue and “fixed” the crack herself.

My uncle also distrusts dentists, though I believe his reservations are financial in nature. He used to Mexico to get his dental work done, and did the same thing for haircuts. This would have been less weird if he didn’t live 1,200 miles from Mexico.

“A piece of me was resting in her palm …”

I think this strange misgiving about dentists must go back further than my grandmother, though. I remember her telling me a story about her own father. When he had a toothache, he would grab some pliers and disappear into the bathroom for a while. When he came out, the tooth would be gone, and the toothache along with it. Or at least I hope so. Now I wonder if he kept all of his pulled-out teeth in a Baggie too, roots and all. Maybe he put them in a glass case to show dinner guests.

————————–

My first tooth extraction was for my top canines, and it was not done with pliers. Though I inherited many dental traits from my ancestors, a fear of dentists was not one of them. My permanent canines got confused on their way down, so instead of pushing out my baby teeth like they were supposed to, they began growing right in front of them. My dad remembers his cousin Thealie having a similar problem, probably passed down from the British side of our family tree. Dr. Everson had to deal with those two. I was about nine by this time. I think I watched Freaky Friday, or part of it, while breathing in laughing gas to become calm enough for him to give me a shot of Novocain. I didn’t like the idea of not losing my teeth naturally. It felt wrong somehow, like a copout. But those teeth are included in my menagerie anyway.

In fact, the only teeth of mine that are lost forever are my wisdom teeth. I have no idea where those ended up, since they weren’t given to us after the procedure.

I had my great-grandmother’s early-growing ivories, another inherited gem, and had to have my wisdom teeth extracted when I was about eleven to keep them from damaging my other molars. “Compacted” is what they were, or that’s what I remember the oral surgeon telling us. He was an ancient-looking man, who still lisped from what I hope was not a stroke. My whole face hurt afterward, no matter how many frozen peas I held to my cheeks. I explored the stitches in my gums with my tongue, keeping track of their progress towards dissolving while watching obscure Esther Williams movies. I can still feel a slight lack of bone where they had to drill to get my teeth out, and a connection between the very back of my cheek and gums where I swear there wasn’t a connection before.

The changes to my mouth bother me still. All my other teeth left, only to return in shark-fashion soon after, but my wisdom teeth are gone for good: a little part of me lost in the void, tossed out with the trash, never to return. Or maybe they are kept by the lisping oral surgeon in a dark back room, a private exhibit for his own enjoyment on slow days.

————————–

My own collection of teeth is incomplete, now that I really think about it. But maybe that doesn’t matter. If my baby teeth are more like a museum exhibit, dead and unfinished, then my permanent teeth are like a historical reenactment that moves and lives, carrying on a long tradition with their own unique interpretations.

I like the idea that my teeth aren’t just mine. I have a little bit of Uncle Ed, a dash of cousin Thealie, a glimmer of Great-Grandma Helen, and who knows who else, all tied up in one mouth. Perhaps I had a prehistoric ancestor with an open-bite. Or maybe I’m related to a well-to-do Victorian woman with confused canines. Maybe these traits were how my ancient family members identified people who belonged to their clan.

Or perhaps I am graced with especially rare traits that occur only once every three generations, like my compacted wisdom teeth. I suppose I can forgive my teeth a little for trying to sneak back into their old haunts. Maybe they are trying to keep the tradition alive. And no matter how my teeth shift and change through my adulthood, I will always have my Baggie of baby teeth: my own little secret history apart from everyone else’s. A moment of time frozen like a snapshot, preserved from the capricious whims of my ever-changing, living teeth.

____________________________________

Our Winter 2019 issue features lovers, fighters, warriors, war reenactors, ad men, insects, and neighbors. Do we play the game, or does the game play us? What do we get when we spin Fortune’s wheel? Who’s watching, anyway — and when are they coming for us? Read the full issue by clicking here or the cover at left–or explore it via the menu bar above.