A young family takes a risk to return from abroad.

“In the last few years, when I’ve gone abroad it has become an increasingly bigger test of courage to state I’m from the U.S.”

Shortly before leaving England, I took my daughter to our favorite park to let her stomp about a pitted soccer field. It’s an old park surrounded on three sides by woods and on one side by a brick wall of a Victorian-era prison.

Another father was there with two kids: one a toddler the same age as my daughter, keen to push his own stroller; the other was in primary school, huddled over her phone. We got to talking, as people so often do now when emerging from lockdown, and because we were non-white people in an English city. He was Algerian.

We talked missing sports. We talked of COVID news from our homelands. “It’s tough in Algeria, yes,” he said, “but nothing like America.”

“Yes,” I said.

In the last few years, when I’ve gone abroad it has become an increasingly bigger test of courage to state I’m from the U.S. For other nationalities, the opportunity to meet an American is often an opportunity to express dislike, dismay, and disgust. Sometimes, it starts with grievances; other times, with America simply uttered in a hoarse voice, followed by a long quiet stare.

That was how he said it. So, I kept my toddler by my side.

“I’m so sorry for you,” he said. “It’s so sad. But I suppose all empires get sick and fall.” He kept his eyes on me and shook his head in that It’s such a shame sort of way. “Think of the Romans.”

I didn’t know what to say. Usually, this was where I would defend, or clarify, or agree that my country does many things wrong — but then insist that we’re working toward some lofty sense of justice and freedom. But I had never before been pitied for being American — and by a citizen of a country that many of mine couldn’t find on a map, a country that Trump would and probably has called a “shithole.”

Thankfully, I didn’t have to say anything: his toddler tipped over the stroller and fell into a divot in the field where the grass had died. The big sister merely glanced up from her phone long enough to snicker.

As he dusted off one kid and chastised the other, it occurred to him that the good hot dog cart in the parking lot by Poundland — the U.K. version of a dollar store that people like us, who go to pitted soccer fields like this, love — was open again. “Got to hurry before the bloke runs out,” he said.

His toddler waved goodbye. My toddler did too. They’re both at the right age to have figured that one social nicety out.

***

After England, I came home with my family to start a new life teaching in a small school in Iowa. By “home” I mean America; I’d never been to Iowa before. To call anywhere in America “home” is ridiculous in the traditional sense of the word, especially for an Asian guy born within the barbed-wire fences of a U.S. military base in Japan. I spent most of my adult life, too, abroad. But the U.S. to me was the normal, like baseball in summer and American football in fall, supersized meals, mowed lawns, everything available via a drive-thru. Even our protests to make our culture less racist, and our belief that it can be, seem like the way things just have to work as we travel Dr. King’s long “arc of the moral universe” that “bends toward justice.”

When we landed in Atlanta, the CDC came on board our half-empty plane and read aloud the conditions of our stay: self-quarantine, temperature self-checks, masks, etc. That was all part of the new normal. We expected it. What didn’t seem normal was an announcement that I didn’t have time to write down. It sounded a bit like this: You are coming from a highly infected region. These measures are to prevent the disease from spreading to the people of the United States.

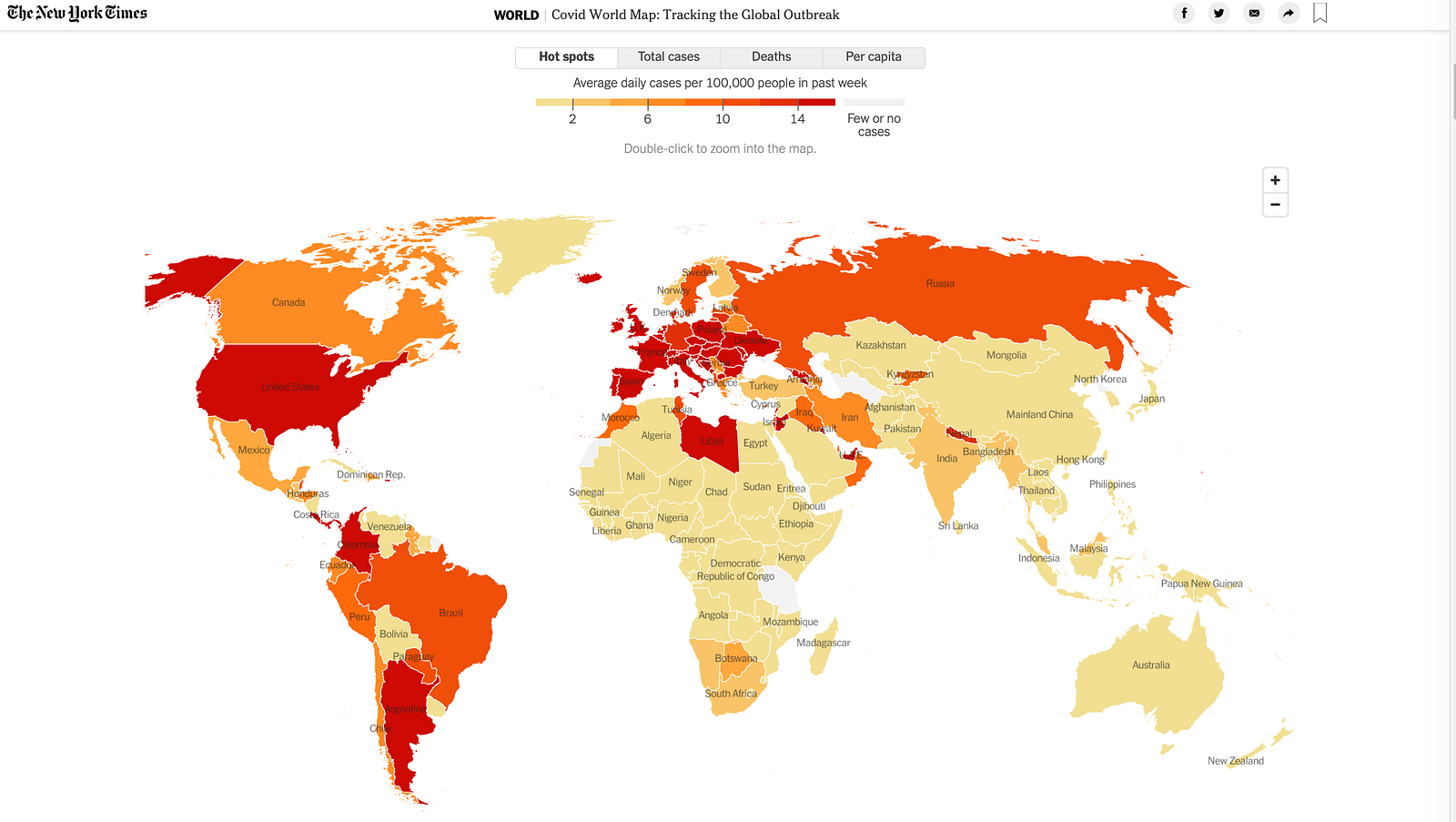

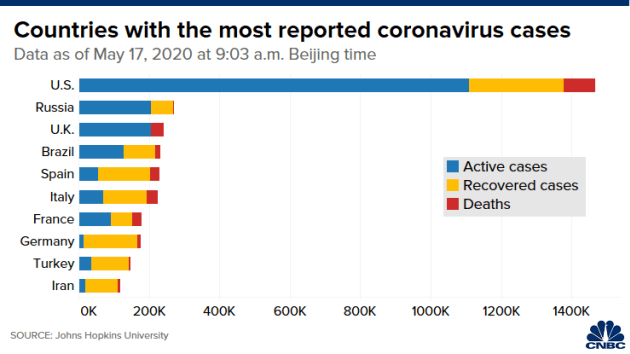

Passengers chuckled beneath their masks. This was August. This flight was from Amsterdam. Europe, and almost all of the developed economies of the world, had emerged from lockdowns with the pandemic relatively under control, unlike the U.S. In the early days, I read about how people with COVID had crazy dreams — like riding lions while falling down endless pits. They’d wake up confused, unable to tell what was normal. Was the CDC confused too? Hadn’t the CDC seen the bar graphs of death where each bar represented a country, and where the American flag towered far above the rest?

In Atlanta, we quarantined at my brother-in-law’s house. Holed up in a room, I planned classes I would teach through a mask. Downstairs, two nephews were on a circuit of games: on their computer, on their Xbox, and finally for a break, they watched other people play games on YouTube on their phones.

Once, I went down to ask them what they were playing. “It’s whatever. I’d rather go to class,” the younger one said.

The older one snorted. “Yeah, home sucks.” He pointed at the screen. “I’ve seen this level too many times.”

I fought back that adult encouraging-yet-chastising voice that asks Why aren’t you doing something productive? Or Why don’t you go outside?

Why ask a question like that when the real question is, What are these kids’ lives going to be like compared to ours when they’re being taught to keep others six feet away, feeling closeness only through web cameras as they slay each other’s avatars with rocket launchers and pickaxes?

“COVID sucks,” they told me.

I agreed.

“I miss seeing people,” the younger one said. The older one grunted and loaded up Starcraft, the original, in order — I think — to show me something my generation would recognize.

***

From Atlanta to Iowa, we drove my father’s car. We had stored it at my brother-in-law’s while we were in the U.K. It was the only thing that I wanted from my father after he passed; it’s an obnoxious little Honda Civic coupe that was built as a single-body, which my father once explained to me meant the car was well built or something, but I can’t remember why. We drove through his old home state of Tennessee and the hills of Kentucky. Then, as the land flattened and we approached the rivers, we saw a Confederate flag bigger than any flag ought to be. This flag carries many meanings: treason and slavery and oligarchy; misplaced pride in homelands; Americans who think they’re so American that they’re no longer Americans but confederates of a lost cause; and the meaning that I took it for, Keep driving. We don’t want Americans like you.

Among grids of corn and soybeans, between the cities, the MAGA flags wave beside mailboxes. In cities, Biden’s name pickets the streets. Flags mark out territory, borders to different lives.

We entered Iowa. As we pulled into a hotel parking lot beside the highway, we saw construction workers gathered around a truck missing its back gate. It was spotted with rust and lumpy with growths of dried mud, as a hard-hat, lunch-pail worker’s truck ought to be.

The men hunched over the truck bed, tired and dirty, were sipping beer and shooting the shit. It was familiar, yet not, because I noticed they weren’t wearing masks. At the front desk, behind a plexiglass pane, receptionists and someone who looks like a manager leaned back in chairs and watched a rerun of Friends. They weren’t wearing masks.

Beside the hand sanitizer was a big sign saying that all employees must wear masks.

The receptionist giving me the keys noticed me looking at the sign. “Oh, you don’t have to wear that thing if you don’t want to. Corporate makes us put that up.” The new normal on this side of the plexiglass said I had to. The old normal on the inside the pane had a TV with Ross listening to his pregnant ex-wife’s stomach. We kept our masks on.

In the morning, I opened the window and saw corn and soy stretching to the horizon. The line was broken only by a single skinny tree, like some abandoned I.V. stand. At one time, this all was trees and shrubs and wilds, right? Was that the lone survivor?

At a truck stop we ate Subway sandwiches. I carried my daughter, who has been blowing kisses to everyone, even when she has her own mask on. “Mask” is one of the few words she learned. This day she blew a kiss to the lady working the Subway line and to an old man eating at one of the two tables not marked off. The Subway lady wanted to give her a cookie. The old man waved back.

***

We got to our small Iowan town. My co-workers are nice; my students are happy to get into a room where they can look at each other under masks and sit at tables wiped down and set six feet apart. My family and I live out of suitcases and eat off the last card table from Walmart and sit on cold metal folding chairs.

Our stuff won’t arrive from England for months: the pandemic slowed everything down. Things we mailed from Atlanta get lost. The warehouse in the nearest IKEA is empty and the giant fans above seem to echo in the empty spaces.

Within a week my daughter is sick. She’s not blowing kisses or smiling. She’s running around with this painful, panicked look, running to the corners of our empty rooms to double over on the carpet, and wails before sleeping. She sleeps for ten minutes and runs and wails for twenty. This goes on all night.

The pediatrician says it’s normal. Not COVID. Because everything not COVID is now normal, like the days when we could go to the clinic without waiting to be escorted in by nurses suited up for surgery.

“It’s just a bug kids get,” the pediatrician says, rushing us to a nurse who can teach us how to take stool samples. “Get some stool, give her meds, and get some rest. Just normal stuff.”

Daughter throws up in the waiting area of the pharmacy. This isn’t normal, I think.

It gets worse. That night, she stops wailing. That scares us more than we’ve ever known we could be scared. I’m reluctant to take her to an emergency room. To do that is to risk COVID. Wife says this isn’t normal, and we’re not waiting, but we don’t move. She holds my daughter, I hold the phone, and we all look up to the stain in the ceiling shaped like a swimming pool because we’re unsure what to do.

We drive on roads so dark you have to use your high beams to keep from running over nurseries of raccoons leading their kits across the lines. There’s no one else out here to blind. We don’t know these roads. They’re empty except for the glint of wild things watching us from the shoulders. We see no other cars.

Only one parent is allowed into the emergency room. COVID. I wait out in the car, in a shaft of light from a streetlamp. I wait for my daughter to get better. I wait for things to arrive from abroad. The smell of smoke from the western fires far away from here, but not far from where I grew up, drifts in through the windows with the cold.

This emergency room doesn’t have the tools they need. We’ll have to drive her to another emergency room that does. It’ll be a day before doctors can name it and fix it for now. They’ll say that they don’t know why it happened or if it will happen again, that we’re lucky, and we’ll all just have to wait and see. But I don’t know that now. I’m just looking back at her empty car seat, in my dead father’s car, at the mask she left behind. I’m hoping she’ll be okay, that I can give her the tiny mask for her to wear like Om-ma and Ap-pah, because that is normal for her, like blowing kisses.

In a few days, when she comes out of the big hospital riding a small Radio Flyer, I’ll forget to bring her tiny mask and get teary when I see the Band-Aids taped where the I.V.’s went. When I hold her, I’ll promise her normal things: some sweet corn, a teddy bear, and a bedtime story, and hope I can get two out of three.

******************************************************

Joe Milan, Jr., was the 2019–20 David T.K. Wong Creative Writing Fellow at the University of East Anglia. In addition, he was a Barrick Graduate Fellow at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. His work has appeared in wonderful places like The Rumpus, Broad Street, F(r)iction, The Kyoto Journal, and others. He is now an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Waldorf University in Iowa.

A previous piece for Broad Street, “I Got Grown,” was one of our Pushcart nominees for 2019, and he contributed to our blog earlier with “No One Ever Waves Back.”

You can read more of his work at joemilanjr.com.