“I often wonder if I am violating the sanctity of the hearts of the writers I teach and write about when my research carries me into the details of their private lives …”

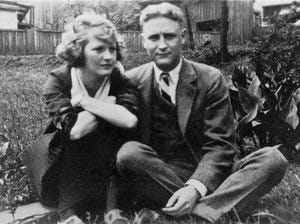

Bryant Mangum sees himself mostly as a scholar — and he is in fact an eminent expert on F. Scott Fitzgerald in particular and the 1920s as a decade — but he’s that unusual writer and teacher who makes the loftiest work appealing to the humble masses who just want a good read.

He’s a collector of rare editions of Scott and Zelda’s work and related ephemera, and he generously shares his finds with aspiring scholars and fans.

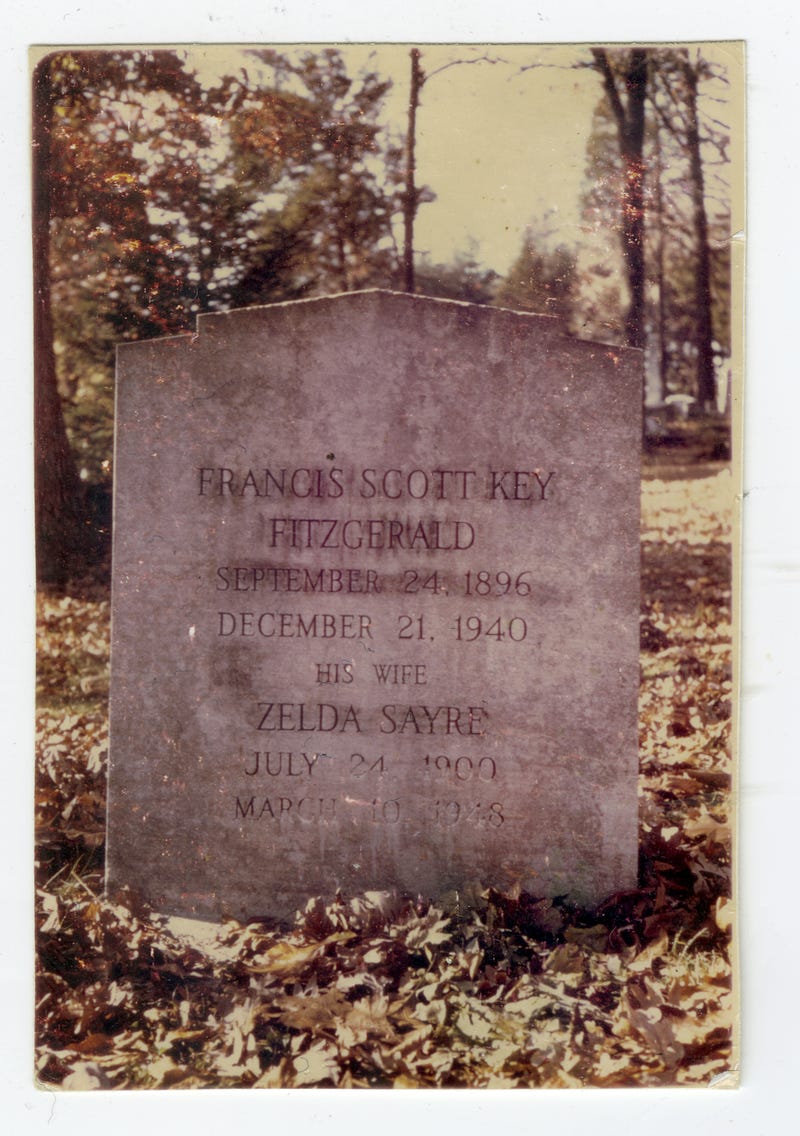

In fact, when we published his essay “An Affair of Youth”—a memoir-essay about the Fitzgeralds and how flappers, belles, and the famous two have shaped our understanding of several cultural phenomena—he gave Broad Street a unique photograph of the Fitzgeralds’ first grave, taken when he and two friends from graduate school made a road trip to find the final resting place of the couple they’d been studying.

It is the only known picture of that gravesite to have been published. (Read through to the end of this interview to see the photo.)

Bryant was naturally the person we most wanted to ask about recent public enthusiasm for the Fitzgeralds and the 1920s. And when we posed our questions, he gave generous answers, proving himself not just a scholar and a gentleman (as we already knew he was) but also, again, a born storyteller and lyrical writer of memoir.

This interview is also posted, in a slightly different format, on Medium.

* * *

Broad Street: Bryant, first the question we ask all our contributors, a question all too relevant these days — how do you define truth?

Bryant: I grew up in a Southern Bible Belt culture in the small town of Darlington, S.C., where almost everyone I knew took seriously the ninth commandment, which forbids lying. Hovering somewhere in or above the Spanish moss in the live oak trees that lined most of the streets of my youth was the possibility that a lie from one’s mouth could bring a lightning bolt from the heavens and strike the liar dead. Speaking the truth, then, became a kind of inoculation against a lightning strike; and truth found definition in its opposite: the lie.

Ours, however, was also a peace-loving culture — a culture that did everything possible to soften what were known colloquially as “hard feelings.” The template for day-to-day conversation that developed — mainly, I think, to minimize the possibility of hurt feelings that might result from direct truth-telling — was one that followed the pattern of Emily Dickinson’s “Tell the truth but tell it slant” philosophy. This slanted speech was the norm quite unintentionally and in a way that did not stress the possible blinding beauty of unvarnished truth, but rather its ability to wound.

The pattern as I saw it involved the learning of a language within a language that contained coded messages, and everyone I knew seemed to understand the code and abide by it. If someone invited you to a party on Saturday night, for example, and if you did not plan to go, your response would be “I’d love to come. Thanks so much for inviting me,” which everyone understood to mean “Much obliged, but I’ll not be there.”

And through this kind of oblique discourse truth was spoken (or untruth was not spoken), the spirit of the ninth commandment was mostly honored, and there were no lightning strikes that I heard about.

On one level, then, truth to me is that which is not a lie — a definition that carries as subtext a proposition made by sixteenth-century Pope Leo X: “Truth cannot contradict truth.”

Another kind of discourse that was an important part of the culture that I knew growing up, and one that has, in the end, shaped my ideas about truth and informed my teaching perhaps as much as anything else, is the tradition of storytelling. In my family and in the families of most of my friends, the oral tradition was strong, and its role was often one of passing down family “history.” It was clear, though, that the rules that governed the telling of stories were different from those that applied to those of everyday conversation, especially in regard to the sacredness of literal or factual truth.

“This slanted speech was the norm quite unintentionally and in a way that did not stress the possible blinding beauty of unvarnished truth, but rather its ability to wound.”

In fact, the stories I remember from my early years were most often preceded by a quick wink or a passing twinkling of the eyes of the storyteller — a not-so-subtle indication that the ninth commandment was being put on hold until further notice.

One example of a story I heard from my father many times in various versions was of a gift his father gave him when my father went off to college during the Great Depression. His father, my grandfather, took from his pocket a gold Waltham pocket watch and gave it to my father with the words, “I don’t have much of value to give you as a token of my love, but I want you to have this watch, which is the most valuable thing I own.”

After my grandfather’s death, my dad discovered that, in the absence of his Waltham, for all those last years of his life his father had carried in his pocket a cheap Westclock pocket watch known as a “dollar watch,” which my father displayed in all its faded and scratched-chromium glory on the mantelpiece in our den. When I left for college my father gave me “the gold Waltham watch” with words to the effect that he was passing down to me the token of my grandfather’s sacrifice.

It was only several years later I discovered that, in fact, the original Waltham watch had been stolen from the glove box of my father’s car when I was still a child, years before he passed “the watch” on to me — thus rendering my Waltham a watch of unknown origin.

And then many more years later I learned that my father was known to many of the pawnbrokers in Savannah, Charleston, and Columbia because he would go around to the shops and buy every gold Waltham he could find, later giving them out one by one to each special person to whom he showed the “dollar watch” and told the story of his father’s sacrificial gift. He gave each with the words, “I want you to have this watch my father gave me when I went off to college.”

“In recalling these stories from my early years I am made conscious of the complexity of my thoughts about truth, and how they have evolved and continue to evolve. Don’t they for us all?”

I have several of the Walthams now in a cigar box on my dresser, and when I look at them I am reminded of how deeply my father believed in and clung to the importance of metaphor in communicating a kind of truth that can transcend factual or literal truth; but stories like this one have also led me to question the process by which literal truth can follow a path through metaphor to become fiction — which, in a best case, tells truth and, in other cases, lies.

All of this in response to your question is a roundabout way of saying that even before I entered the academic world — before I began to study literature seriously and to teach — I was processing the idea of what truth means, and in recalling these stories from my early years I am made conscious of the complexity of my thoughts about truth, and how they have evolved and continue to evolve. Don’t they for us all?

On an earlier occasion you mentioned that you use real stories in your teaching. Will you explain what you mean by “real stories” and how you work to keep truth — or perhaps we should say “honesty” — alive in your teaching?

I should say at the beginning here that I teach literature classes rather than courses in creative writing, and so the central focus in my classes is on the fictional works in my main fields of interest: stories and novels of the Modern and Contemporary periods (in narrowly focused seminars, particularly works of Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Salinger) and stories from The New Yorker. Perhaps ninety percent of the time and effort in each class is devoted to looking carefully at the texts, typically eight or more books each semester. But in the case of each of these books, whether novels or short story collections, there is always the question of opening the door on the work — of contextualizing it, of setting out the blueprint for the approach to it, and in the case of some works that don’t seem immediately accessible to students, of providing a point of connection that will encourage students to enter it, hopefully with excitement.

It is typically in this last area of providing a point of connection that I use “real stories,” by which I mean autobiographical stories. In my Introduction to English Studies class last semester, for example, students were having difficulty (to my surprise) finding a point of connection with James Joyce’s story “Araby” — and with his concept of the epiphany.

When I discovered this, I told a story of an experience I had in my sixth year, when I climbed, as I often did after I had gotten home from school, onto the roof of the barn behind our house. I lay on my back happily, without a worry in the world, taking in the treetops around me and gazing at the sky.

The roof was corrugated tin and had collected a shallow layer of dirt onto which chinaberries had fallen from a massive chinaberry tree that grew beside the barn. On the day in question, I looked over at dozens of small seedlings that had sprouted from chinaberries that had fallen from the large tree onto the roof’s shallow layer of dirt, and I realized that they would either grow so big that the barn roof would collapse, or that because the shallow soil would not allow the roots to grow deep, the trees would all die.

With my sudden awareness of these possibilities and with this flash of insight — this epiphany — the innocent world that I had known moments before seemed no longer to exist. Like the narrator of “Araby,” I felt myself “a creature derided by vanity” to have believed my carefree world of after-school rooftop sky gazing — a world where I could lie peacefully and without worry among chinaberry seedlings — would last forever.

Almost immediately after relating this story to the class, I found that virtually every student in the class had her or his own barn rooftop story and most had come to feel kinship with the narrator of “Araby.” The idea of the epiphany became for the class more than an academic construct, and the story became, even with its unfamiliar setting of a cul-de-sac in early twentieth century Dublin, a bearer of profound truth.

In this case the chinaberry tree story I told was literally true. Telling it as it happened was an honest attempt to provide the class a point of contact with Joyce’s story. The truth of my story matched pretty closely part of the truth of “Araby.” And in fact, because of the lack of complexity of my story when placed next to Joyce’s beautifully layered narrative the class became able to more fully appreciate the richness and lyricism of “Araby.”

“When one uses ‘real stories,’ I think that person becomes something of a memoirist, and the question becomes whether or not a slight alteration in a real story — the addition, say, of a minor invented detail — renders the real story fiction.”

It is always tempting when using autobiographical stories, in the way I did with “Araby,” to embellish the “true” story so that its parallels fit more neatly with the fictional story onto which you are opening the door for other readers. I try to resist this impulse to embellish, and have mostly been able to. On those occasions when I have not resisted, I have employed the wink or the twinkling-of-eyes maneuver that I learned from the storytellers of my youth, attempting in good faith to alert a group to the fact that the ninth commandment was being placed temporarily on hold, and that we were for the moment blurring the line between fact and fiction.

I strongly agree with Mary Karr’s idea (beautifully described in her The Art of Memoir and displayed in The Liars’ Club, Cherry, and Lit) that memoir must be an honest telling of the truth as one remembers it.

When one uses “real stories” in teaching, I think that person becomes something of a memoirist, and the question becomes whether or not a slight alteration in a real story — the addition, say, of a minor invented detail — renders the real story fiction. Reasonable people will disagree on where a line between fact and fiction lies and subsequently perhaps even where the line between honesty and dishonesty is crossed.

Writing of the kind you do is so often meant for a wide audience, while oral traditions can be very personal. What, to you, is the relationship between public and private when it comes to truth and honesty?

It’s certainly true that the oral tradition, which often finds its first audience with family, is more personal. And there seems to come with this tradition a higher level of directness that does not always come with those essays and books written for a wider audience — which may be another way of saying that there is more truth and honesty in the oral tradition.

This may help account for the directness often found in memoirs like Mary Karr’s, fragments of which often have found their earliest audiences in informal family settings where family secrets form the heart of narrative.

In Karr’s case, her family prided itself on some of the more bizarre actions of its family members. Her mother was proud, for example, of having shot at Karr’s father and at another husband; and she seemed not at all bothered by the fact that Karr wrote of her having tried to kill Karr with a butcher knife. Such family details, with no objections from her mother, worked their way into Karr’s memoirs, written for a wide public audience.

The question that this kind of sharing raises—when narrative leaves the oral tradition, with its limited audience, and enters the public sphere—is whether every detail that has been a part of shared experience between two or more people in the private world is fair game for inclusion in a work that will go into the public domain. As an example, in Lit, Karr tells stories involving her relationship with her ex-husband, including intimate details related to their private life together.

A question that this raises in turn is whether a writer by making available for public consumption details that have been shared between two people in private betrays the confidence of another person. Or as Hawthorne might ask it, Does this violate the sanctity of another’s heart? Where does one draw the line in pursuing truth and honesty when recounting a “real story”?

Fiction writers, at least partly, are able to avoid this problem, as does Elena Ferrante, for one example, who opts to fictionalize experience rather than to write it as memoir. Based on her essays in Frantumaglia, one can clearly see that Ferrante is writing from autobiographical material in each of her four Neapolitan novels (My Brilliant Friend, The Story of a New Name, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, and The Story of the Lost Child).

In her choice to fictionalize her experiences, and unquestionably embellish them, she may at least partially shield from public scrutiny the prototypes of those characters that she writes about in her fiction. Whether she violates the sanctity of another’s heart in this process is an open question — a question to be answered only perhaps by one whose heart has been tampered with.

Now I have to ask it — Do you ever feel you’ve violated the Fitzgeralds’ sanctity?

I probably felt this most acutely years ago when I presented at an MLA conference a paper on the way that I believed Scott and Zelda were communicating with each other in a coded way through Zelda’s publication of Save Me the Waltz in 1932 and Scott’s publication in 1934 of Tender Is the Night. The paper I presented was meant to demonstrate how one could break the code of the communication between the two novels and understand what Scott and Zelda were saying to each other in a deeply private way.

I’ve managed to steer clear of this kind of meddling in recent years, but just over a year ago, I wrote a book chapter describing the seven substantial volumes of letters containing large samplings of the more than three thousand letters Fitzgerald wrote during his lifetime and, in addition, many of the thousands of letters, now published, that he received.

Writing this chapter involved reading and rereading all of the published letters, and often as I was reading them I felt that I was violating the privacy of those who had not imagined that one day a stranger would be reading what they had written.

And so to answer your question: I do often wonder if I am violating the sanctity of the hearts of the writers I teach and write about when my research carries me into the details of their private lives.

I would be remiss if I didn’t ask you about the recent spate of Fitzgerald-related pop culture, such as Baz Luhrmann’s film of The Great Gatsby and the TV shows Z: The Beginning of Everything (which was based on a novel) and The Last Tycoon. Recent novels have included Gatsby’s Girl and Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter. Have you watched or read any of these? Do you have a critical opinion to pass on?

I saw the Baz Luhrmann film version of The Great Gatsby on its opening night, and I binge-watched the nine episodes of Amazon Prime’s The Last Tycoon. I also watched the pilot episode of Z: The Beginning of Everything, and I plan to go back and see all of the episodes. I have personal preferences, of course, but I haven’t considered them analytically, so I don’t have a critical opinion to offer.

I haven’t read Gatsby’s Girl or Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter, but my sincere hope is that the pop culture interest in the Fitzgeralds will lead people to go back and read Zelda’s Save Me the Waltz and Scott’s The Last Tycoon, The Great Gatsby, and Tender Is the Night.

The 1920s seem more fashionable than ever, usually romanticized the way Fitzgerald romanticized the girls in his short stories and novels, as you write about so beautifully in “An Affair of Youth.” Then there are really gritty takes on the era, as in Boardwalk Empire, which I found fascinating in its visual detail and examination of multiple forms of criminal empire, including an African American crime boss. How do you see works like this contributing to — or taking away from — Fitzgerald’s portrait of the era?

The current fascination with the Fitzgeralds in popular culture, and particularly with the romanticizing of Jazz Age culture, reminds me of a similar trend that was evident in the early to mid-1970s. It was a time when The Great Gatsby came into the cultural foreground with the release of the Robert Redford — Mia Farrow film version, and the novel was reliably selling more than 500,000 copies per year. Fashion magazines of the early 1970s were filled with clothing styles of the Roaring Twenties, and the Gatsby film itself was featured on the cover of Newsweek.

Scott and Zelda’s daughter, Scottie, was asked her opinion as to why her father had come into such vogue at the time, and she gave her opinion in a 1974 article in Family Circle. She attributed the upsurge of interest in what she called “the most conspicuously ‘forgotten’ author of modern times” partly to nostalgia for a time when things seemed, at least on the surface, glittering.

Scottie acknowledged that her father had captured the allure of the superficial glamor of the Roaring Twenties, but she attributed much of the renewal of interest in his work to his ability to see the dark underside of the sparkling surface: “[h]e was a prophet . . . [a]nd the rebellion of his generation which he helped to create, was the herald of the larger, deeper one taking place today. People read him now for clues and guidelines as if by understanding him and his beautiful and damned period, they could see more clearly what’s wrong.”

This 1970s revival of interest in Fitzgerald’s work coincided with the dark political time of the Nixon administration and of Watergate. Nixon resigned in 1974 — the year of Scottie’s comments and the year of the release of the Redford-Farrow Gatsby film. And now, more than forty years later, and again in what many see as an ominous time in the national political world — with perhaps the foreshadowing of a dark time in American culture generally — we again have an upsurge of interest in the 1920s and of Fitzgerald, often in representations romanticizing the time that he so brilliantly captured.

“‘All the stories that came into my head had a touch of disaster in them.’”

Fitzgerald was alert to the danger signals in the 1920s, as he wrote in an American Calvacade article in the late 1930s: “All the stories that came into my head [in the Roaring Twenties] had a touch of disaster in them — the lovely young creatures in my novels went to ruin, the diamond mountains of my short stories blew up, my millionaires were as beautiful and damned as Thomas Hardy’s peasants.”

By the late 1940s, Hollywood had come to recognize the prophetic aspect of Fitzgerald’s greatest novel: The Alan Ladd — Betty Field film version of The Great Gatsby (1949) was a dark gangster film.

In the end, it seems plausible that Scottie’s observations about the reasons for her father’s increased popularity in the 1970s could hold true for the revival of interest in the popular culture in the late 2010s. People may be looking to him “for clues and guidelines as if by understanding him and his beautiful and damned period, they could see more clearly what’s wrong.”

Those grittier treatments of the Roaring Twenties, such as Boardwalk Empire,suggest that our present popular culture understands this: the romantic melody of the 1920s that lingers on may tell, as Fitzgerald knew, only part of the story.