Raymond Chandler’s inaugural novel gets scholarly treatment in a book packed with facts, photos, and insights into the text and the times.

“We all had great love for Chandler’s novels. And we knew the world did too.”

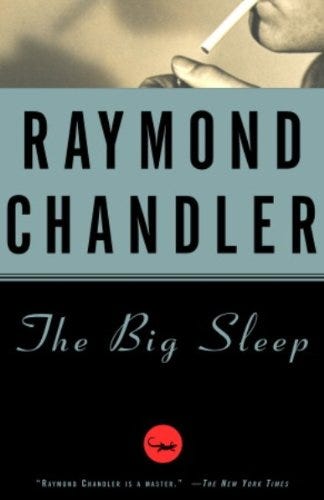

Some years ago, three intrepid friends who met at a bookstore —Owen Hill, Pamela Jackson, and Anthony Dean Rizzuto — undertook a monumental project: annotating Raymond Chandler’s seminal novel from the perspectives of literary criticism, cultural history, and any other lens that helped see deeper into the work. The result is The Annotated Big Sleep, published by Penguin Random House in July 2018, with a forward by Jonathan Lethem.

As Lethem writes, “Nothing, even a book as singular and archetypal as The Big Sleep, comes from nowhere. What a gift, to see in part how Chandler made it. Under just three names, these annotators number among them two poets, an archivist and literary scholar, a gifted crime novelist, and three sleuths; reading it conveys the vicarious thrill of their innumerable discoveries. Chandler lucked out.”

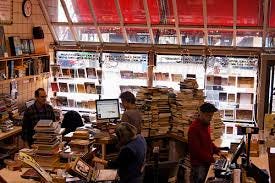

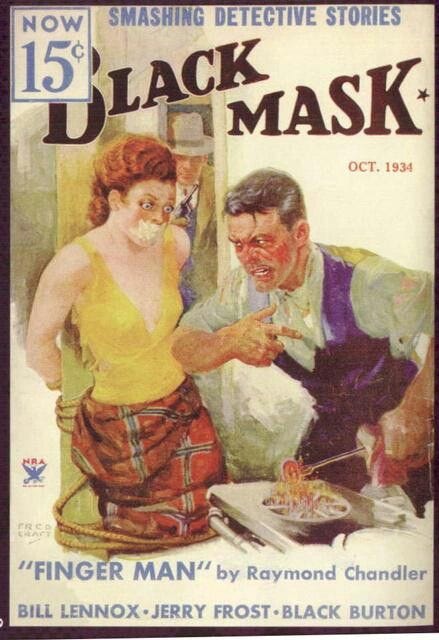

Chandler began writing fiction at the age of forty-five, after a career as an oil executive. He published his first story in Black Mask in 1933, and he’d go on to write seven novels, several screenplays, and numerous short stories, and to become the master of American crime fiction.

This edition has been warmly received by critics and readers. As of August 1, Amazon.com officially declared it a bestseller, placing #1 in mystery and detective literary criticism. And it’s one of Broad Street’s favorite reads of the season, in any genre.

Reading the book along with the annotations is like having a long, leisurely, Nabokovian chat in the salon of friends who are both erudite and down-to-earth. You’ll find gems of fact and insight on every page, until it might start to feel natural to set aside Chandler’s text (on the left-side pages) and read the annotations straight through for a while. Like Charles Kinbote’s annotations to John Shade’s Pale Fire, they make a story of their own.

And now for the story behind the story: We ask the three annotators about the genesis of the project, how they worked together, what they love about Chandler, and whether the collaboration ever threatened to veer into noir territory.

—interviewed by Susann Cokal

This feature is also available, in slightly different format, on Medium.

******************************************************************************

“Chandler was inventing, reinventing, and honing not just a literary genre but an American mythology: the tough, wise-cracking loner who stands up to corruption.”

Origins

First of all, why Chandler, and why this book in particular? What place do you feel it occupies in literary history, and why is the time ripe for an annotated edition now?

Anthony: Why Chandler? We all had great love for his novels. And we knew the world did too. I couldn’t believe it hadn’t been done yet.

Owen: Before I did this, I didn’t fully realize that Chandler, while building on the work of Hammett and other hardboiled authors, was inventing, reinventing, and honing not just a literary genre but an American mythology: the tough, wise-cracking loner who stands up to corruption.

In any given week, the New York Times bestseller list is dominated by mysteries and by protagonists that somehow carry Marlowe’s DNA.

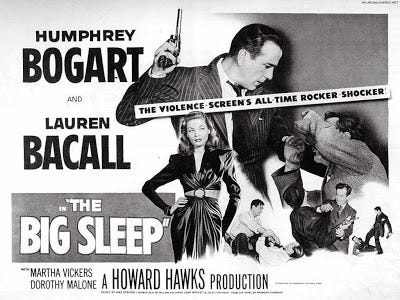

Anthony: I’d say: If it was going to be Chandler, it had to be The Big Sleep. It’s more than just his first novel, it’s his inaugural novel; it introduces Marlowe and the host of themes Chandler would take on in novel form over the next two decades. It was also Chandler’s first and greatest attempt to introduce a more “literary” style to the hardboiled genre he’d been working with in the pulps for most of the decade. It’s the turning point for Chandler.

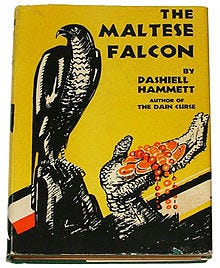

Image: The novel’s first edition, 1939.

Whose idea was it to start the project, and how did you all get together?

Anthony: It was my idea. Owen and our friend Dan Liebowitz encouraged me to read the Marlowe novels, and once I did, I couldn’t stop. I’ve always loved annotated editions — Martin Gardner’s Annotated Alice was one of my first favorite books. I’m the kind of guy who reads footnotes to everything, even scholarly books; I’m always disappointed when scholars only give references in their notes, rather than expanding and playing on the body of their texts. After I read Chandler once through, I wanted to go back and read him again in an annotated edition, and there wasn’t one. So I proposed that we do it.

Owen: I had been reading Chandler since I was a teenager, rereading every few years. My first novel, The Chandler Apartments, is kind of an homage, but I hadn’t thought of doing anything like this.

Pamela: I had heard Owen and Anthony bandying the idea about for a while, and I had just finished another book, so I jumped in and helped write a proposal. Like them, I couldn’t believe it hadn’t already been done. It just seemed so obvious.

Image: Owen’s first novel, named in partial homage to Chandler.

“The only hard part with Chandler is deciding where to stop. You start digging into something small — an odd turn of phrase, a street name — and it opens into a whole world.”

What do you think it takes — qualities of character, emotion, mind — to turn a favorite book into a research project?

Pamela: For me it came naturally. It was like starting a conversation. Who wouldn’t want to have a conversation with their favorite book? And then you also get to bring the book into conversation with everything else — the world it was written in, and your own world, other books and stories, its author, the genre it helped to shape. And Chandler makes it easy. There are just so many places to jump in and ask questions, and such a wealth of other material to bring into the conversation, from his own writings, the pulps, Hollywood, the newspapers of the day…my own research started with the 1939 L.A. street directory!

The only hard part with Chandler is deciding where to stop. You start digging into something small — an odd turn of phrase, a street name — and it opens into a whole world.

To what extent would you say this conversation was organic and seamless, and to what extent did you have to make a conscious effort to set aside your love of the book and relate to it intellectually?

Anthony: Love and intellect don’t occupy different spheres, at least in my brain. The great thing about Chandler is that he’s endlessly interesting while he’s just being a great writer. He’s embedded in so many political issues of his time that are also ours: political corruption, the decadence of capitalism, police brutality, the politics of gender and sexuality and ethnicity. That’s all in The Big Sleep. And even where (as with any of his identity politics) critique is more required than celebration (as with his general socio-political stance), it’s important and interesting to have that discussion. So, love and critique go hand in hand.

On Collaboration

The three of you come from different intellectual and creative backgrounds: Owen is a poet, novelist, and bookseller; Pamela is a librarian, editor, and scholar with a doctorate; and Anthony is also a scholar and a bookseller as well as a professor of multiethnic literature.

I suppose the first question that arises is, How did you all find each other? And did one or more of you already have this Chandler project in mind when you formed the trio?

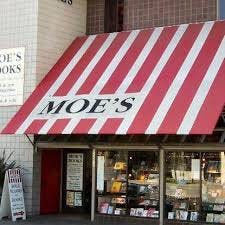

Anthony: The great literary bastion that is Moe’s Books on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley is the intersection point here. Owen, Pam, and I all met as workers at Moe’s, at one time or another. Dan Liebowitz, who suggested I read Chandler in the first place, was the captain of Moe’s; even Jonathan Lethem worked there, before he left for his writing career. That’s how we all know each other and how the project was born.

Owen: I’ve worked with Anthony for many years, and if you work in a bookstore you talk about books.

This led to a friendship, and, eventually (years later), this project. I met Pam through Jonathan Lethem, who at the time was about to leave his job Moe’s to devote his life to writing.

Pamela: Yes, Moe’s is like a big, revolving research library, where any book in the world could walk in the door and start you off in a whole new direction. It was perfect training for an annotator!

What unique skills and insights did each of you bring to the project? You can speak for yourself or praise your collaborators here.

Owen: I had written a couple of crime novels, and I’m a huge fan of the genre. I came at it from that angle. I also had big ideas about how this book should be written, style-wise. I wanted it to be punchy (one reviewer has used the word), readable, short on jargon (except where absolutely necessary).

Also, I’m a frustrated film critic (less frustrated now) and wanted to write about film noir. I don’t have the training that Anthony and Pam have, so research presented a learning curve. I tried to follow their lead, and I was often surprised and delighted by what they’d find, and how we would incorporate our research into the text.

Pamela: Owen hasn’t mentioned his skills as negotiator and peacekeeper. He gets credit for keeping all of us talking to each other and the project more or less on track. We’d never have made it to the finish line without him.

I think I mainly brought my curiosity, my interest in the conversation. I’m endlessly curious about the backstory — where a great work of art comes from, how it came to be. Which is a question that points in so many directions, to the mysteries of authorship but also historical context, genre, culture. I loved the chance to dive into all of these things. And I’m a research geek, so really, any excuse to read the 1939 L.A. street directory — can you believe it’s actually online at the LAPL website? I love that stuff.

Another part of the backstory that absolutely fascinated me was the way The Big Sleep borrows from Chandler’s early short stories. Chandler knew what he was doing — he called it “cannibalizing” — and I took on the task of piecing together exactly what parts of the novel came from which story, figuring out how he fit it all together and what he changed in the rewrite. There’s so much to learn in that about Chandler as a writer and about the novel itself.

You can see how deliberate his choices are, and how hard he worked to craft his style. Chandler often said that plot wasn’t important to him, that he really only cared about style, or “the music,” as he put it once. And the truth of that really hits you when you look at TBS next to these stories. Put them side by side, and you find whole scenes that are almost exactly the same, except for the music.

Anthony: Pam did a great deal of wonderful historical research! And Owen wrote lines as only he could have, with his poet’s eye for brevity (different from mine, as you can tell).

Owen has an inimitable, understated style, which I love. He also helped me smooth out my style a bit: I began in a high-academic register, and he constantly reminded me that our audience wouldn’t primarily be scholars and college students.

I guess what I brought was a background in literary theory and criticism, an eye for genre play and an ear for intertextuality. I wrote a lot of the stuff about gender politics too. As a feminist teacher of literature and having discussed the book with over a thousand students now, the majority of them women, I felt compelled to mine that vein.

“At some point we started thinking and writing alike, a strange sort of alchemy.”

How did you go about managing the project as a group? Most obviously, how did you divide the work?

Owen: We had some early meetings where we divided the work, and there was a bare-bones template, but there was lots of spillover. Getting together physically was tough due to conflicting schedules, so we worked electronically on a shared document. There was lots of revising and reworking. At this point I can only identify small portions of the work as completely “mine.” Annotations where I initially took the lead have been edited and improved. At some point we started thinking and writing alike, a strange sort of alchemy.

Pamela: There were some obvious areas of expertise and interest that naturally sent us in different directions — me to L.A. history and culture and the pulps, Owen to Hollywood and crime, Anthony to literature and Romanticism, but then we basically stepped all over each other because the more you get into the novel and your own research, the more opinionated you get, and the more your territory bleeds into everyone else’s. And yes, it got bloody!

Anthony: We had one meeting where we assigned words and passages through about the first quarter of the book. But after that it was kind of a free-for-all. Some stuff that appears early is continued as a motif throughout the book, so the same person took that on. Pam pursued the thread of early L.A. history; I did a lot on the figure of the knight and the romance motif and the sexual politics; Owen followed linguistic and political threads that called out to him.

Because we collaborated digitally, there were opportunities to respond to what each other wrote, and also to add on, with permission. There was a lot of respect between us for what each of us was doing, and trying to do, along the way. Not to mention reliance on each other! If I wrote about the romance stuff, or Pam covered early L.A., no one else had to! That went for everything we did.

Owen: The conversations we had led (I hope) to organic and seamless annotations, but the conversion was something else. I had done very little critical writing, unless you count book reviews, so I had to come to a writing style that fit and do some on-the-job training.

I don’t think my love of the book got in the way of that. It really kept me going. One reviewer used the word “enthusiastic” and I love that. This is a scholarly study, but it isn’t dry criticism. In many ways it’s an appreciation.

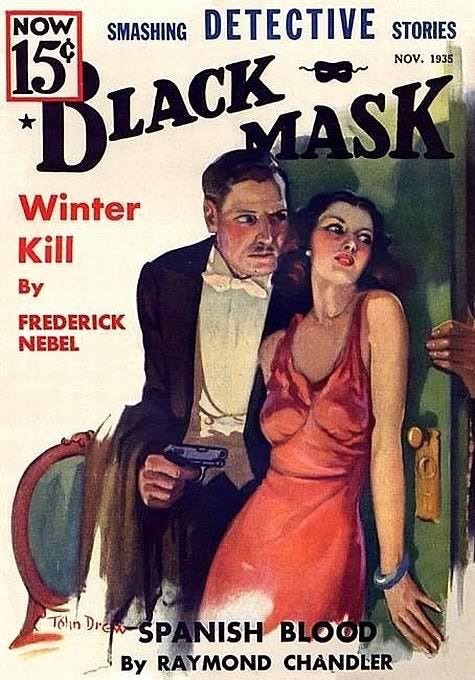

Image: Pamela’s previous work parsed Philip K. Dick.

“There was a lot of respect between us for what each of us was doing, and trying to do, along the way.”

Were there ever any spectacular disagreements between two or all of you? If so, what did you disagree about, and how did you resolve the situation?

Anthony: You’ll have to wait for The Annotated Annotated Big Sleep for those answers!

Owen: I don’t think they reached the point of spectacular. There would be disagreements, but then there would be some deadline and we’d be forced come up with something.

Pamela: Some of the more interesting disagreements were over the role of the annotator. I argued for a lighter touch that left more room for readers to interpret the book their own way, for example (I lost, as you can see!). There were other, similar arguments — should we have a dense and scholarly introduction, or a short and breezy one? How much should we give away — should there be spoiler alerts? Do we need to define this word, or that word? We didn’t really resolve most of these issues. Like Owen said, the deadline resolved them.

Did anyone come to blows or start plotting violence during an angry, sleepless night?

Anthony: Ditto my previous answer.

Pamela: A lot comes up when you’re collaborating with two other people. I think of myself as a good collaborator — all my big projects have been collaborations — but for three people to annotate a text they all have strong feelings and opinions about is very tricky. And we didn’t lay down any ground rules at the beginning. How will we resolve disagreements? What’s the division of labor? Can we fire each other? That sort of thing.

Owen: Yes, I did have some of those nights, but not so much because of my co-annotators. I somehow caught the hot potato and ended up working with permissions, so most of my “urge to kill” fantasies were directed toward people who were demanding outrageous sums for snippets of material. It was also frustrating that two editors at Vintage quit during the project. Nobody’s fault, but for a few months (while waiting for a new editor) there was lots of crankiness — ok, occasionally directed toward my co-annotators.

Truth in Fiction

As you may know, our motto is “True stories, honestly,” and we’re a magazine of entirely nonfiction prose and poetry. But we’re also interested in belles-lettres and the myriad truths that build a sustained fictional world in novels and other forms of imaginative writing. This is one reason your Chandler project is so gripping to us; you’ve done a thorough, even exhaustive, job of unpacking cultural references and noting ways in which Chandler builds literary effect.

Anthony: THANK YOU!!!

On the very first page, for example, you trace the genealogy of the powder blue suit Marlowe is wearing, and you also point out that the sky is unusually gray and the expected blue has transferred to the suit (which he wears without the fedora and trench coat that would become his cinematic uniform). Later on (e.g., page 431), you point out exactly what Marlowe can see in a confrontation and record the moment at which he shifts from light wit to “outright sarcasm.” You provide an impressive history of Los Angeles’s Bunker Hill neighborhood, among other places, in both history and literature (359). And your book is loaded with photographs of the places, houses, and objects important to the novel.

This kind of work is life’s blood to the literary scholar and avid fans of Chandler, but some readers — I’m thinking of undergraduate students in a general-education course [Anthony: Ha! that is where I teach The Big Sleep!] or beginning workshop, who worry about this a lot — might protest that digging too deep into the facts and analyzing the technique could spoil their pleasure in the story.

Could you respond to that (for the moment imaginary) protest by explaining how your relationship to the novel and to Chandler’s work in general changed as you worked on the annotations?

Image: A recent cover, redesigned for 2002.

Owen: One strategy for the first-time reader is to read the novel straight through without reading the annotations, then go back. There’s a lot to appreciate.

The argument for this annotated edition is that it is one of the great American novels. If the reader is perhaps too young to recognize the slang, or isn’t familiar with the genre, this edition can be helpful, but it isn’t just one of those study editions with notes. The novel has great depth, and a knowledge of, say, the history of Los Angeles, makes it even more interesting.

Anthony: I’m reminded of one of Kinbote’s comments in Pale Fire: “I trust the reader appreciates the strangeness of this, because if he does not, there is no sense in writing poems, or notes to poems, or anything at all.”

Pamela: I already read as a literary scholar, so I’m ruined as far as that goes! But I’d say I probably appreciate the novel more now than I did starting out, or at least have a deeper connection to it. I had thought I already knew the book, but I could never have guessed it would reward the annotator with so many unexpected gifts. I hope some of that sense of discovery translates for readers as well.

But that said, I agree with Owen — in fact I’d say it more strongly: read the book straight through first without the notes. I’d be sorry to take that experience away!

Anthony: I know some people will think we could have remained more “factual” in the notes, but that’s not the spirit that Chandler inspires, and it’s not the spirit we set out with. Chandler was embedded, as he was well aware, in a deep literary and cultural milieu, and the fun was in tracing the patterns that he was set in and that he set in motion!

How do you recommend readers experience the book — text and annotations simultaneously or one at a time, alternating between text and notes, or some other method?

Pamela: I can never quite decide how to read an annotated edition, but I’m pretty sure that bouncing back and forth five times on one page isn’t the best way. I’m hoping people will tell me what worked for them.

“Knowing what I know now, the background, the history…the next reading will be even more rewarding.”

Another question that might come from that person often referred to as the “common reader”: Now that you’ve done all this research, do you think you’ll be able to read the book “innocently” again, for the sheer pleasure of plot and image and whatever else inspires you to read a book for the first time?

Owen: At various points I swore I’d never read TBS again, but I was lying to myself. We recently organized a couple of readings from the book by favorite writers. Hearing it read aloud, I was reminded of the exquisite beauty of the prose.

There are passages that can be read, over and over, as poetry. Knowing what I know now, the background, the history…the next reading will be even more rewarding.

But I may wait a few years!

Anthony: I actually think that Chandler never was “innocent” in that sense. He was always playing around and commenting on many levels. And really, is any “literary” author “innocent”? Aren’t they all guilty of playing off of and within networks of cultural and literary meaning?

Shoot, isn’t that what we mean by “literature”?

Or maybe I just gave my confession as to the kind of reader I am. Guilty. As charged.

The Details

You must have known some “fun facts” about arcane aspects of the book when you started out, then discovered new gems as you did the research. Could each of you share one or two favorite discoveries here?

Anthony: I wrote a piece identifying some of these, so I’ll let Owen and Pam answer this one.

Pamela: I’ve mentioned a few of my favorite discoveries already, like the way Chandler “cannibalized” his other stories. Another gem along that line was finding out how much he borrowed from Dashiell Hammett. It’s not one of his better-known works, but Hammett’s weird gothic murder mystery, The Dain Curse, is clearly an influence on TBS. And there’s a fight scene in TBS that’s ripped right out of The Maltese Falcon.

In his letters, Chandler is always quite open about what he owes to other writers. There’s a great story he tells to mystery writer Erle Stanley Gardner. He says he learned to write detective stories by studying one of Gardner’s short stories. He’d read a scene, then write it as best he could from memory. Then he’d look back at the story and see where he’d gone off track, and then he’d go back and rewrite it again.

He repeated that until he figured out how it was done — the pacing, the dialogue, the movement of plot. I’ve never quite tried doing that myself, but I think it’s such a great idea! And finding out all this just made the originality and artistry of TBS come through for me all the more.

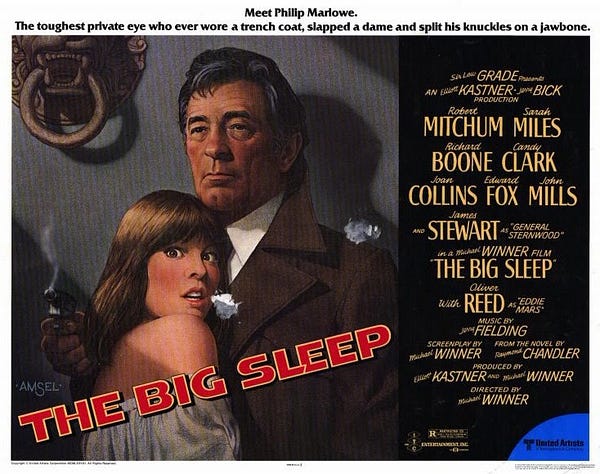

Owen: I had heard the story that Howard Hawks had contacted Chandler to ask him who killed Owen Taylor — that loose end in the book. Chandler reportedly said “I don’t know,” or some version of that. I began reading movie bios and interviews — a favorite pastime of mine anyway — and found several versions of that story. Bacall, Hawks, Leigh Brackett (screenwriter) and, finally Mitchum, had all “been there.” A reporter at the L.A. Times helped me find an interview with Mitchum where he claims to have been in a bookstore backroom when Chandler took the question.

It’s a great game of “telephone,” full of conflicting details. Maybe there’s a “fun fact” hidden somewhere in their stories.

Is there some piece of information or some connection that you were dying to discover but couldn’t find? Do you have any questions you’d like to crowd-source for ideas?

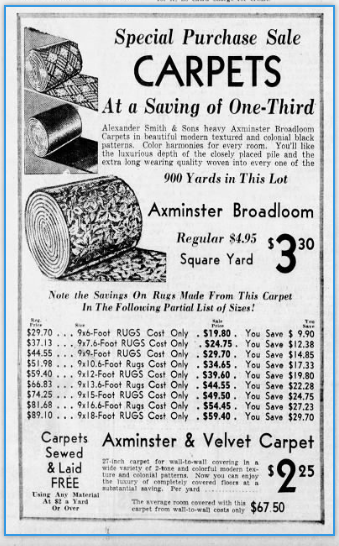

Pamela: The first page I opened the book to when I got my copy was the beginning of Chapter 3, where Marlowe meets Vivian Sternwood for the first time. I looked at that first passage, and it suddenly struck me that I had forgotten the note I meant to write on the history of wall-to-wall carpeting! I not only forgot to write it, I forgot to research it.

What’s the history of wall-to wall-carpeting? Anyone? I’m quite sure no one but me will miss that note, but it’s going to drive me crazy until I find out if there’s a good story in it …

Image: A newspaper ad for wall-to-wall carpeting, March 1939.

Owen: I had occasion to visit Tom Williams, Chandler’s most recent biographer, who told me that there was an interview with Bacall where she talks about the novel and names it as one of her favorite books. Williams hadn’t found the interview, so I guess my chances were slim. I hunted around as much as I could, but nothing surfaced. It would have been a great quote to use, either as an annotation or a blurb. Sadly, Bacall died while we were working on the book. I had fantasized leaving a copy with the doorman at the Dakota in NYC, where she lived.

Anthony: There are two!

1) When Eddie Mars says to Marlowe in Chapter 21 that “You talk a good game. But I daresay you can break a hundred and ten,” is he putting him down or giving him respect? The “break a hundred and ten” reference is to golf. Mars is saying Marlowe would play a good game. Do readers hear respect, or a put-down?

2) I’m always curious if other people have a favorite candidate for the “filthy name” that Carmen calls Marlowe in Chapter 24, and if so, what it is. I have my own theory…

“He was one of the great ones.”

And finally …

Is there anything we haven’t asked that you’d like to talk about? We’re happy to give a platform to just about anything you’d like to discuss …

Owen: Chandler and other mystery writers hoped to be taken seriously as “literary” writers. Thanks to “crossover” writers like Atkinson, Auster, Lethem, and so on, crime writing is less ghettoized, but I’d like to have some hand in erasing those lines.

Hopefully, we’ve helped readers to think of Chandler’s work alongside some of the other authors we mention in the book: Cather, Fitzgerald, Hemingway.

He was one of the great ones.

Thanks to all three of you for this fascinating book and interview. And here’s to the readers who will now be able to enjoy The Big Sleep in greater depth!

Anthony: Thanks again to you! Such wonderful feedback. We wrote this book for you and people like you!

******************************************************************

More on the Annotators

OWEN HILL is the author of two mystery novels, a book of short fiction, and several books of poetry. He has reviewed crime novels for the Los Angeles Times and the East Bay Express. In 2005 he was awarded the Howard Moss residency for poetry at Yaddo. He is currently coediting the Berkeley Noir anthology, forthcoming in 2020.

PAMELA JACKSON is an editor, scholar, and librarian specializing in California literary and cultural history. She holds a PhD from UC Berkeley and an MLIS from UCLA. She was coeditor, with Jonathan Lethem, of The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick.

ANTHONY DEAN RIZZUTO is a professor of English at Sonoma State University, where he teaches (among other things) California ethnic literature and hard-boiled fiction. He earned his PhD from the University of Virginia.

True stories, honestly.