From Our Pages: “Miniature,” by Leslie Stainton.

by broadstreetmag on Jan 31, 2019 • 10:35 am 1 Comment“Hitty attributes her survival to her ‘smallness,’ which, she insists, appeals to the strangers who save her, one after another.”

BROAD STREET presents a popular feature about love, loss, and the things we carry throughout our lives, from our 2018 “Small Things, Partial Cures” issue.

This essay is also available, in slightly different format, on Medium.

Miniature

A life dwindles down to the smallest.

Leslie Stainton

Among the items I retrieved from her condo after my mother’s death was a book called Hitty: Her First Hundred Years, a volume I associate with a tiny doll my mother kept near her throughout her life. For decades the doll resided in the top drawer of her dresser, and then, in later years, in a tin cookie box on her bedside table, together with other precious objects: a silver pocket knife, two wedding rings, a pair of wristwatches, assorted figurines.

The doll — who was not in fact the Hitty of the book but a doll with her own history — lay inside a cardboard container no bigger than a matchbox, wrapped in a shred of tissue paper. She was the size of the topmost joint of my index finger. Black hair, porcelain face, infinitesimal limbs. So tiny an infant’s hand could crush her, which is perhaps why my mother so seldom let me hold the doll. Only a few times (if that) in my life, the fragile treasure was lifted from its reliquary and placed in my grasping palm while my mother hovered over the affair like a priest at communion.

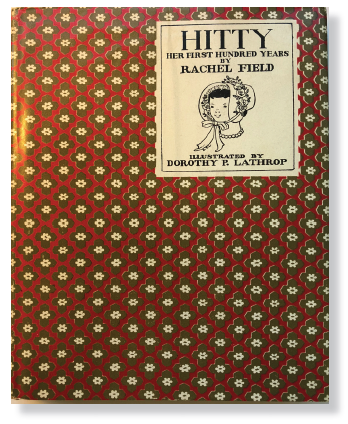

Recently, as the first anniversary of my mother’s death approached, I opened Hitty and began reading. The book is covered in a faded pink fabric flecked with flowers. Inside, there is a bookplate showing my mother’s name and an image of a young girl with yellow hair wearing a long pink dress. She holds an enormous bouquet of red flowers, some of which appear to have sprung loose and attached themselves to her hair, others of which are strewn at her feet across a bright green hill. A hillock. She looks like a princess on a small green throne.

Hitty professes to be the autobiography of a wooden doll who lives in an antique shop in New York City at the time she writes her story. It is of course fiction, written by best-selling novelist Rachel Field, who won a coveted Newbery medal for the book. The year of the book’s publication is 1929, when my mother was eight.

I started reading the first chapter (“In Which I Begin My Memoirs”) and soon came to a passage in which Phoebe Preble, the little girl who first owns Hitty, and Phoebe’s mother cross-stitch the doll’s name onto her dress, which they refer to as a “chemise.” The doll’s full name is Mehitabel — a name I recall my mother repeating — but her owners soon shorten it to Hitty.

The china doll in the tin box on my mother’s bedside table also wore a chemise, a muslin sheath no bigger than a thimble with tiny red embroidery at the neck, and as I read about Phoebe and her mother and their doll, I wondered if my mother had done the stitching herself, perhaps in imitation of Phoebe and her mother. She must have told me, but I’ve forgotten. I only know how precious the baby was to her.

“There,” said Phoebe’s mother when the last stitch was done, “now whatever happens to her she can always be sure of her name.”

“But nothing is ever going to happen to her, Mother!” cried the little girl, “because she will always be my doll.”

How strange it seems to remember those words now! [Hitty writes.] How little we thought then of all that was so soon to befall us!

My mother was not a sentimental person, at least not in obvious ways. She did not, for example, build her Hitty an enormous dollhouse in her spare room, as her neighbors did for their dolls — a couple in their eighties who worshiped things miniature so much that they devoted nearly a full room of their condo to their cultivation. Gaston Bachelard writes — in words that speak to my own experience — that we covet the small because “the tiny things we imagine simply take us back to childhood, to familiarity with toys and the reality of toys.”

My mother often talked about her early years, which were spent in Haiti, where her father managed a sisal plantation. I can only guess that the doll Mehitabel — for I now realize this is what my mother called the matchbox baby after all — came from there. Perhaps “Mehitabel” was a legacy of French colonial rule, as were other objects in my mother’s possession (a gold necklace, a set of ornately decorated apothecary jars). She and her brother and sister grew up in a white stucco house staffed by Haitian women with names like Ta Gras, derived from “Alta Gracia.” The address of this mythical place, I recall, was Ti-Calle-La, meaning “Little Street.” Again, the diminutive.

Try though I do, I cannot conjure this lost world. The plantation today is in ruins, decades after the rise of synthetic rope and the collapse of the sisal industry. My mother is gone. I did not pay enough attention while she lived (does anyone?), and the details are now irretrievable.

In my own childhood, it was my brother and I who built a massive dollhouse on a table in a spare room in our house in Pennsylvania, creating a home within a home where we could impose a collective, if fraught, order on what we must have sensed was chaos. My mother did her best to keep things

thrumming. The daily tidying and vacuuming, the lunchboxes and grocery lists. The struggle to hold it all together — distant spouse, a daughter with cerebral palsy (my sister), disobedient kids (I shoplifted, my brother stole).

Years later, my brother and sister and I would agree that we mostly remember our mother angry. Slamming doors or plates or my sister’s wheelchair. Heavy sighs. The constant effort to appease my father, to hurry up dinner so he wouldn’t drink himself into a stupor before bedtime.

Only in small moments would we connect. I remember a Christmas morning when she and I shared cups of sugared coffee in my bedroom before daybreak. We’d both woken early and couldn’t sleep. I was five. I cherish the scene as if it were my own small baby lying in a matchbox.

Or the occasional tea sessions she staged with a child-sized set of colored china cups, sitting before the fireplace on the living-room floor, sipping the milky fluid.

The miniature makes us dream, Bachelard says. Enter its world, and immediately images begin “to abound, then grow, then escape.”

In the last weeks of her life, my mother shriveled. The fierce woman of my childhood — the woman I’d battled so often, so often criticized, attacked, hated — became brittle. Stick legs and arms, gaunt face, porcelain skin. Her eyes were black hollows, somehow both blank and inquisitive. She sat halfway up in bed and tugged at her clothes: the faded cotton pajamas she’d worn for years, a blue gingham print flocked with tiny blue flowers. Her hair no longer yellow but white — but still: flowers.

“Somebody give me a hug!” she cried one morning.

In her eighties, she and my father had downsized from their five-bedroom house in the suburbs to a condo in a retirement community. They’d hired someone to help them move — a kind and efficient woman who spent weeks advising my mother on what to discard and what to keep.

In the end, exhausted, her back a wreck, my mother took to bed in the new condo she already loathed, and I came in to help clear out the last of the debris from the old house and organize what remained in the new. I almost enjoyed the task of redecorating, fitting my parents’ worn belongings into sleek new quarters. It was as if I were a kid again, constructing a dollhouse in the spare room, arranging tchotchkes on its shelves. My brother and I worked to make the new place as pretty as the old. Prettier. But my mother never accepted it.

Her bones hollowed and she began to stoop even more. “Welcome to the land of the shrunken people!” she greeted my stepchildren one day after we’d driven in from Michigan to visit. Her eyesight dwindled, too. Robbed of vision — the sense that had made her a fine watercolorist and draughtsman — she took to using a magnifying glass, that old-fashioned tool beloved by detectives and children.

And then her mind began to mottle, and soon she could not retain a thought for longer than five minutes.

“How are the kids? What are they doing? How’s Steve?”

“They’re fine. Everyone’s fine. The kids are in college.”

“That’s good.”

Pause.

“How are the kids? What are they doing?”

I hated visiting.

On one of her lucid days, my mother asked me, “Who’s going to take this?” She was standing beside a small wooden bookcase in the front hall of the condo. “My father built it for me when I went away to school. Promise me one of you will take it.”

The case held little — a pottery vase into which my mother had stuck a dried flower; a box of coins; a copy of Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country, a novel she loved because it reminded her of Haiti; and Hitty: Her First Hundred Years.

“One of us will take it, Mom. Don’t worry.”

I made a mental note: Keep this, Leslie. And I have.

Later, repeatedly, she admonished me, “When the time comes, don’t feel you need to be here.”

When the time came, and my brother and I were there, she said, “Thank God you came. I don’t know what I would have done if you hadn’t.”

A CT scan had found tumors in her chest. Her doctor told us she had weeks, at most, to live.

In her last days she craved orange juice. “Oh,” she cooed, “has anything ever tasted so good? So good!” The world reduced to a plastic glass held by a nurse. At the very end, because she could hardly swallow, they doctored the juice with powder to give it the consistency of runny Jell-O. “What’s this?” she croaked. “It tastes thick.” And then: “I could drink gallons and gallons of orange juice. I could drown in a sea of orange juice.” I guessed she was revisiting her past, Christmases in Haiti when the toe of her stocking always held an orange. The bright scent of childhood.

And then she became too fragile to save. A tall man in a pinstriped suit, a figure from Charles Addams, whose cartoons my mother had always enjoyed, wrapped her in a cotton sheet and twisted the ends and rolled her onto a gurney — the doll whose face, growing cold, had by then morphed into the half-open scream of Munch’s waterside figure.

It was an August afternoon. The weeks of her dying had been uncommonly cool, but that day and the next, the weather turned humid and warm, as if the atmosphere had been holding its breath and needed to exhale.

Throughout her supposed autobiography, the doll Hitty undergoes a sequence of adventures in which she is separated from her owners and lost — attacked by crows, left under a church pew, shipwrecked, stolen, dropped in a gutter, seized by natives on a remote island in the Pacific and worshiped as an idol. She is six inches tall and unable to communicate, but she continues to be rescued. At one point Hitty attributes her survival to her “smallness,” which, she insists, appeals to the strangers who save her, one after another.

Skimming the book in the summer after my mother’s death, I found myself wanting, but unable, to cry. Did I miss her? My grief is so slight.

The day after she died, my brother and I bundled up our mother’s clothes and took them to Goodwill. We told ourselves we were doing it for the sake of our father, who was infirm and liable to rupture, we thought, if he beheld her belongings. In truth, we were doing it for ourselves. I couldn’t bear seeing the pathetic garments of her last years. The threadbare pullovers she’d insisted on wearing even after we’d bought her new tops. The row of shoes on the closet floor, waiting for their owner like steadfast dogs. I tore through her jewelry, making rash decisions. I wanted to be rid of her, of her dying, which had taken years, it seemed.

On her bedside table I found the tin cookie box with its sacred trinkets, among them the miniature china doll. My mother had kept it all these years in its matchbox, this relic of her childhood on an island in the Caribbean. Nestled beside it, under folds of paper toweling, were a silver fruit knife that had belonged to her mother (perhaps the one my grandmother used when she peeled and ate a dozen oranges by herself in the back seat of a car in Haiti in the 1920s, a story my mother loved to repeat); a cushioned box holding my mother’s wedding band and an infinitesimal gold ring she’d received as an infant; a pair of women’s wristwatches; a figurine of a saint, and another of a Chinese baby, made of bisque and broken at the waist. This, too, was no bigger than the crook of my finger.

I tucked the cookie box into my backpack and the next day left for home.

At the airport, TSA nabbed the fruit knife. I said it had belonged to my mother, who had just died.

“I’m sorry, but you can’t take it. You can mail it home if you like.”

“Then just throw it away,” I snarled. For the first time in weeks I began to sob. “I don’t care. Throw it away.”

The agent took the knife and disappeared. I went through security, stillsobbing. Inside the airport I came to my senses and went back to him. “I’ve changed my mind. I’d like the knife. I want to mail it home.”

The agent led me to a locked metal box — all the while holding his hand out to keep me at bay — and gingerly retrieved the fruit knife.

“Thank you.” I wept. I walked back out into the airport lobby and bought an envelope and sealed the knife inside it and stamped the thing and dropped it into a mailbox.

Three days later the envelope arrived at my house in Michigan with one edge torn open: the knife had slipped out.

As in the Gospels, my betrayals mounted. In my frenzy to unpack after getting home, I emptied my backpack and with it the tin cookie box. I put its contents in a drawer and tossed the box itself, with the paper toweling in which my mother had wrapped everything, into the recycling bin. It wasn’t until the empty envelope reached my mailbox, on the morning after trash day, that I realized my mother’s doll had been inside the paper toweling, so featherweight I’d missed it. Her Hitty was now somewhere in Ann Arbor’s

recycling facility.

How small a life is. How quickly we discard the dead. Burn them, poison them, enshroud and recycle them.

My mother, my sad half-blind forgetful fragile mother, the one who took my hand and let me hold her treasured doll a few times in my life, had, I thought, in this box that I had so briskly destroyed, endeavored to preserve her soul. Her secret self, the doll within the doll within the doll.

Months later, after my father had gone into a nursing home and my brother and I were emptying what remained of their condo, I found in her files a copy of a letter she had written to her parents in 1979, when the crisis at Three Mile Island was threatening her existence thirty miles away, and she thought she might have to leave home for good. The letter ended with this paragraph:

I have a little tin box with the touchstones

of my life — a little statue of Ste.

Therese that one of you gave me — that’s

for Haiti. My tiny doll — that’s for my

childhood. A funny Chinese baby — broken —

that’s for my sister. A ring Mildred

left me — that’s for her side of my life. Any

one of these things I can look at, and I’ve

got everything that means anything to me.

The doll Hitty narrates her life as if endowed with human capacities, and it is easy to get swept up in the conceit that she actually lived. As I worked my way through the book, I pictured my mother reading Hitty: Her First Hundred Years as a little girl, believing in the power of her own thumb-sized Mehitabel to transcend mortality. The people, mostly children, who lose Hitty have no idea of her subsequent life, or lives, and this is the book’s essential gift — the oblique nod to an afterlife — a gift I now see my mother extended to me when she pointed to the small bookcase her father had made, whose lower shelf held the faded volume, and asked, “Who’s going to take this?” To my knowledge, Hitty is the only book my mother kept from her childhood.

“This is the book’s essential gift — the oblique nod to an afterlife.”

Sometimes when I close my eyes — at yoga, for instance, or in church — I see my mother’s face as if behind gauze. Eyes open, skin as bleached as china. The illusory doll of my daydreaming.

As depressed as she was, when death announced itself, she rose to the task. The mind, previously so addled, slipped a portion of dementia’s noose. She asked questions. She said what she needed to. What would I do without you? she said to us.

My last image of her alive — or rather, the last image I want to retain — is of a pale figure propped in bed, wrapped in white, whispering to herself. She is unaware I am in the room. She is, I can see, talking to God.

“Take me,” she murmurs. “Take me. Take me.”

*******************************************************************************

Leslie Stainton is the author of two books of nonfiction, Lorca: A Dream of Life and Staging Ground: An American Theater and Its Ghosts. Her essays have appeared in The American Scholar, The Sun, and Michigan Quarterly Review, among others.