The ballast of civil disobedience …

“It is possible to break the law without being disobedient, and to disobediently follow it.”

–

This feature is also available, in slightly different format, on Medium.

–

The Art of Living with the Unacceptable

—

Sweat sinks into sandstone, and the sunbaked rock under my hands darkens from brick to rust. Four fingers and two rubber-shoed toes keep me hanging here, with seventy feet of rope spooling from my harness to the earth below. Patrick holds the other end, ready to cinch his grip if I fall. Sandy friction grates my skin as I reposition my fingers within the narrow crack splitting my vision.

Utah’s desert climbing is a practice of agony-induced focus. The surrounding quiet sharpens to a hum as I torque the bones of each finger a notch farther. One more breath and it’s time to move — or fall.

Above and below me, the crack arcs so cleanly that its black edges look laser-cut and charred. This ebony varnish obscures most traces of the many who have hung here before me — their salt-ring pockmarks of exertion, and smears of now-dried blood, are visible only atop the porous orange sandstone. A glance toward my feet barely registers the bouldered jumble below. My eyes snag instead on the colorful pieces of metal clanking on my harness — just one of those, unclipped, grasped, and slid into the crack’s maw, would shorten a fall by at least fifteen feet. Their metal edges bump and shimmer against my hip like the scales of a fish rubbed the wrong way. But experience knows, There’s no time for hooking in now.

Instead, one more torque for slipping fingers. Exertion’s undeniable truth: stability is stunted and momentary. On the wall, I am always on the verge of coming unhinged. Movement is mandatory. As I lean back to wiggle one foot free, the rock’s pressure concentrates around my four slotted knuckles. The slight protrusion of these joints keeps me from peeling off the cliff as I jam my big toe into the crack again, higher this time. To stand up on it, I ease one hand loose, breathe into the increased pressure hammering my remaining two fingers, and re-slot my hand above my head, positioning my fingers precisely within the crack by feel so that the bones hold when I pull up on them. Upward progress, hard-won, is a precise choreography.

And then, a switch flips. In the space of a heartbeat, pain evaporates into the blue of a desert sky above cinnamon cliffs. Suddenly the blood puddled in my ragged cuticle is a jewel spilling luxuriously over my furrowed knuckle, and the unrelenting rub of rock is a finger smoothing a poppy petal. Each point of contact is an articulation of devotion.

Up, up. When I clip the anchor and lean back into my harness, the pain pulses afresh, but I laugh and melt into the warmth of palms pressed against sun-drenched stone.

Patrick cheers, and I no longer hate him with a dark and oozing passion for standing barefoot on level ground. The slant of piercing sunlight, the wide arrangements of improbable clouds, the fleeting views into uninhabited and seamlessly subsiding valleys — in this place everything is perfect, every time. A miracle, or the patterned workings of nature; I’ve never understood the difference.

I grin and raise a fist above my head in celebration. But with this gesture I remember — and my laughter curdles, becomes a staccato bark that quickly dissipates in thin desert air. My fist opens and a breeze blows my slick fingers dry.

The fist — Resist.

From newly minted National Monument to unprotected status in under twelve months: Our highest politicians are determined to open these valleys to the oil and gas industry.

***

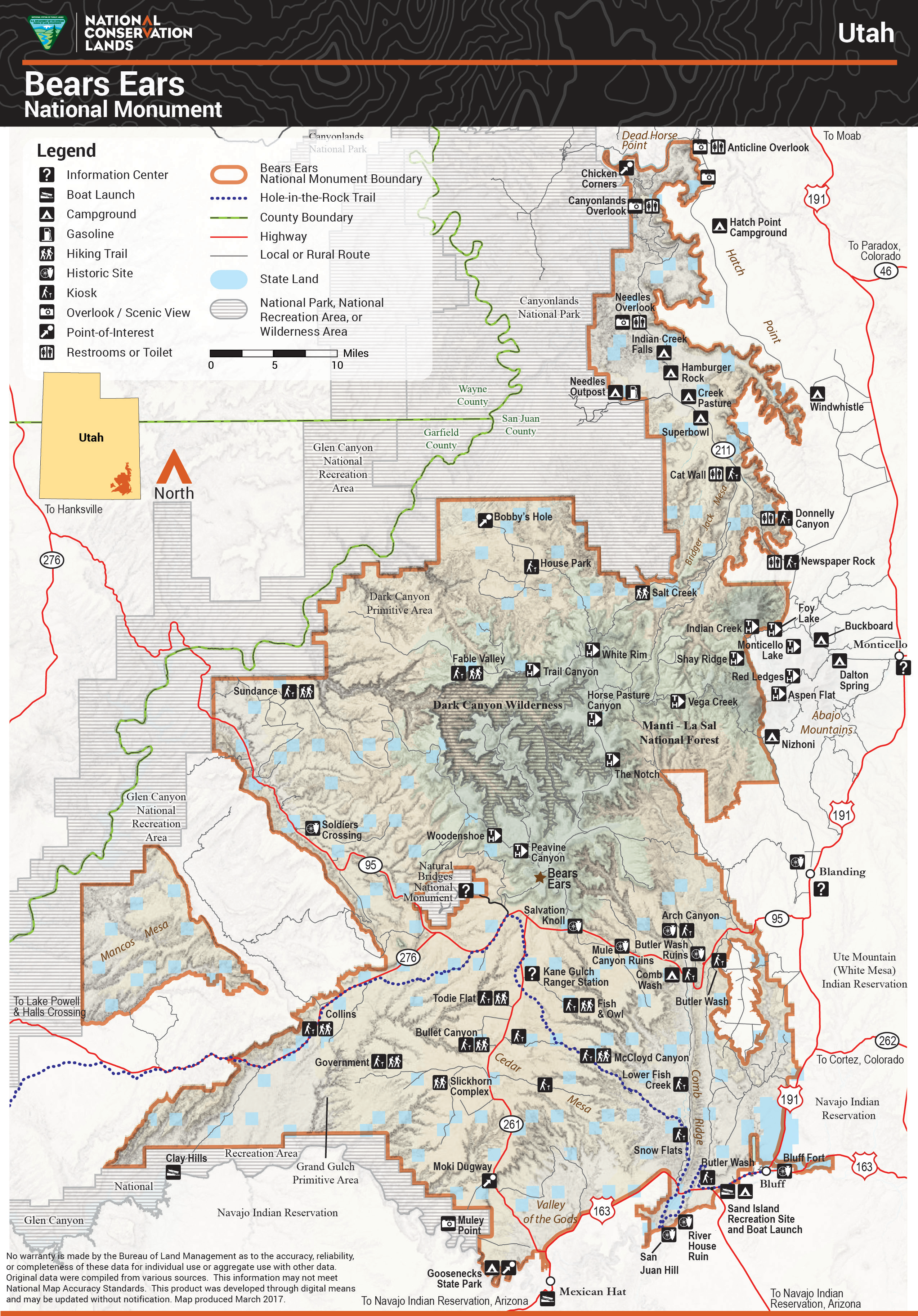

On December 28, 2016, a line was drawn around what would become Bears Ears National Monument. A coalition of tribes seeking the protection of their ancestral homelands, widely recognized as one of the most culturally significant landscapes in the United States, came together with enchanted outdoor enthusiasts and the interests of hundreds of unique desert species. Then came the pen stroke of a president. As I read the final lines of Barack Obama’s proclamation — “I, President of the United States of America, by the authority vested in me, proclaim these lands” — I found myself crying. With disbelief, with relief, full of windfall-wonder, and full of fury. One suited man in a faraway city could shield this place in a way far beyond my capacities. He created a 1.35-million-acre protected area.

Or at least he tried. In the following year, a newly sworn in businessman commanded his new Secretary of the Interior — a man who, as Montana’s District 01 representative, had in 2015 received over $160,000 in campaign donations from oil companies — to justify crossing this line out. National Monument protections hinder extraction-based development.

Around this time, the America First Energy Plan replaced the former White House’s climate-change website. Here you used to be able to find the President’s pledge to open up $50 trillion in untapped shale, oil, and natural gas reserves in our country. (The document is still viewable on sites not maintained by the Trump White House.) As journalist Steve Horn explains, underlying the land of Bears Ears National Monument is a large shale field, site of $773,000 worth of Department of Energy research since 2012.

By the time the April tulips began to bloom in my high-elevation town in Northern Arizona, Ryan Zinke had been put in charge of reviewing dozens of National Monuments to determine whether they adhered to two requirements set out by the Antiquities Act: that they protect at least the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of cultural (not natural) artifacts, and that they be established following adequate governmental engagement with the public.

We all knew then what was coming. But this knowledge was nothing against what stood to be lost. So rallies were held, petitions signed, lawsuits filed. Posters and signs were made: Sacred Places; Keep Your Tiny Hands Off Our Public Lands; Sell Your Soul Much?; Honor Tribes; Lock Him Up.

These cries were brushed off like flies. Zinke developed a habit of holding closed-door meetings with politicians and ranchers. Those indebted to extractive industries or their lobbies, be they logging, drilling, or grazing, comprised most of the small minority of semi-locals who supported shrinking the monument. Everyone’s got to make a living — or to buy a second, third, hell, why not fourth, home: Rob Bishop, a Utah congressman, has collected over $500,000 from oil companies over the last two decades.

By the time I heard that Zinke had taken a single county commissioner on a helicopter ride in lieu of holding an open meeting for public comments, I wasn’t surprised that he’d then been gifted with an emblazoned cowboy hat: Make San Juan County Great Again.

***

“The footing is precarious when you try to stand for something that makes you a hypocrite.”

Amidst the frenzy, and National Monument or not, the land remained. Some people come from their place; an unlucky birth made me search for mine. I may not stay, may not spin my life around one stable core, but that changes nothing.

Over and over again, I return. Maybe this time the cottonwoods pillowing the central wash in the valley are topped with yellow leaves, achingly ephemeral, or they might be crowned with rasping branches, or perhaps thrusting forth new buds with an assurance and faith I can only envy. Maybe their tufted seeds weight the air. The spaces between wide, juniper-topped valleys might be snow-sifted, or dotted with yucca stalks barely visible beneath bell-shaped flowers lined up like the jingles of a tambourine. Amoebic aspen groves, maybe pulsing gold, molten and poured if it’s the season, unfurl on the plateaus and hills above.

But down below, where the humans are, there is also this: the time I entered the campsite bathroom to find a porn magazine rolled up and wedged into the toilet paper dispenser. And not long after that, the time I clambered onto a ledge at the top of a climb to be greeted by the outline of a dick chalked onto the rock in front of me. Also there are the countless times that I try not to keep track of when someone, usually a man, has looked over my shoulder to ask Patrick if they can borrow his cams — the metal pieces you put into the cracks here to keep yourself from hitting the ground if you fall while climbing. The thing is, more than half of those cams belong to me.

Belonging is slippery. And yet — whenever I arrive again, I have no doubt: Yes, this place.

Fitting my body into crack after crack within the cliffs of these valleys, I’ve cleaned countless anchors. Each time I make it to the top I take a sagey, sand-dusted breath and feel the cut-out skyline of towers always nearby pierce my skin, my separateness. Lowering to the ground, I cross my ankles one on top of the other and sip the view as I slowly spin around the axis of dangling rope.

***

“I imagine the valley we’re driving through scarred, shattered, to fuel a few days of … people like me driving from the places they make their money to the places they want to be.”

Civil disobedience comes in many flavors, with two unifying ingredients: the belief that the people writing the rules are the only ones profiting from the status quo, and the conviction that no institutionally sanctioned pathway will change this. Time and time again, marginalized groups have been galvanized into operating outside of legal confines in an attempt to restructure unacceptable norms; hence the Civil Rights movement in the United States, women’s suffrage movements worldwide, and the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. In my time, the urgency of a new reason to sharpen illegal action as a tool with which to create a different future grows: Whether you call it monkeywrenching, eco-terrorism, ecotage, or something else entirely, environmentally motivated civil disobedience — along with global temperatures and ecosystem degradation — is on the rise.

In the decades following my 1989 birth, a fringe fear of climate change has solidified into a widespread recognition of a global environmental crisis perpetrated and ignored by Big Oil, mainstream politicians, and, often, the behavior of every single one of us reading these words.

My life has unfolded amidst a growing pile of evidence that showcases the catastrophic failure of our attempt to treat nature as fundamentally more than a resource bank to feed our civilization’s growth. This bucking planet is my inheritance. My generation is no longer sure that the future will be better than the past. Yet we, too, are wired to appreciate beauty: rare flocks of sandhill cranes, red rock cliffs, the gait of blue-bellied lizards, and canyon walls turned moonlight-white. In this global context, we cradle our treasures with fierce love, unwilling to imagine a world where the word wild is used only to describe the rapaciousness of our greed.

And so the creak of oil rigs, the spluttering gasps of ever rarer species, and the gurgling of spilled oil are taken up as the battle cries of those who refuse to continue business as usual in an era of escalating environmental destruction, consumerism, and the climate change not just circling overhead but devouring our future like roadkill as we veer into the far lane, away from the spreading blood. It is the battle cry of those who risk their bodies, their freedom, their résumés and retirement funds to fight for the future of this planet and the lives it harbors. Of those who, literally or figuratively, throw sand into the machine — and they are many.

The activists’ choices call upon practical imagination — a human talent for envisioning a future that is different than the present. Of course things can be different. They already, always, are: Greenhouse gases currently in the atmosphere will soon send global temperatures soaring beyond the two-degree increase cited as our catastrophe line — the difference between a merely unpleasant world and an uninhabitable one.

You probably know this, have already read the litany of evidence. The list is long and many of its consequences are invisible: the plants and animals that disappear; the unborn children who inherit the dangers of this sickening planet; the submerged habitats and homes lost to rising water; the gases wafting over our heads; the chemicals coursing through our waterways; the rising account balances of the disproportionately powerful few still convinced that piles of paper are the ultimate good; the hearts that break as homes fracture. Don’t forget: Invisible problems are not abstract.

Do these truths become easier to swallow with each exposure? How have we honed that art that Breyten Breytenbach, South African anti-apartheid activist, attributes especially to Americans: “the art of living with the unacceptable?” If you’re more comfortable questioning, even answering, than acting, then, like me, you’re likely to appreciate activist Annette Klapstein’s line of reasoning. Klapstein, a retired attorney with a silky gray bob cut, was one of five people involved in a coordinated illegal action to shut off the flow of Canadian crude oil into the U.S. in the fall of 2016. In an interview given after carrying out this act of “moral necessity,” Klapstein argued that retired white people are the ones who should be doing her kind of work — committing acts of civil disobedience: “We no longer have jobs to worry about,” she reasoned. “We no longer have children at home. If risks have to be taken, we have to take them.”

I like her thinking, of course, because it excuses me — excuses me from adding my body, my future, to those risking arrest and physical harm to undermine the injustices of our political and economic system. Those putting, finally, their bodies between what they love, what we all need, and the societal mechanisms busily destroying it for endless profit.

As reported in Orion Magazine, the amount of crude oil that the valve turners stopped from flowing through those five pipelines that October day equaled approximately 15 percent of daily U.S. fossil fuel consumption — “as it happens, about the percentage by which fossil fuel use must be reduced each year in order to prevent runaway climate catastrophe.”

According to BallotPedia, which obtained figures from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), domestic production from over 63,000 federal “onshore” oil and gas wells on BLM lands accounts for 11 percent of the U.S. natural gas supply and 5 percent of our oil supply. These wells have become uncertain grenades in the pit of my stomach as I return, endlessly, to that one cluster of BLM-managed and no longer federally protected valleys. BallotPedia notes that the BLM did not specify the time span in which data was collected for the 2015 report.

Unlike Klapstein, I’m not retired; I sometimes have a job, though no children. Someone else, then, can make futile sacrifices rather than merely mourn as irreplaceable landscapes are transformed from life-sustaining ecosystems into ravaged profit fields mechanically churning out pollution on an unprecedented scale and transforming devastation into piles of cash.

Unfortunately for my sense of absolution, Klapstein went on in that Orion interview: “If you are an older white person, this is your job. Those of us in privileged positions are not likely to be beaten or killed by the police.”

Shit. How old is older? Thirty? Maybe not, but the silky skin revealed when I twist my forearm is parchment white. “Young activists and people of color don’t have the same safety we have,” Klapstein said.

Yes, my freedom from debt bespeaks not only a decade of scrimping, sleeping on friend’s porches or under the stars, and tipping my body headfirst over Dumpster lips to scrounge for half-bruised vegetables. It is evidence of my position.

Yes, privileged.

***

“My home is an ecosystem, no less so because my government mines it — undermines it — to power my lifestyle.”

Driving back down into the valley on another trip, my tires hum on asphalt, and the half-closed window rattles gently. Gasoline streams through the car’s motor like sand through an hourglass. I extend my arm into the night and breathe in. The cross-breeze carries lingering scents of sun-baked sandstone and the fine orange dust it is always becoming. Once again I tingle from the inside out as cliffs rise and the straight road leaves the junipered shrubland and begins to wind downward. My elation mingles with a wordless calm, the mosaicked sensations reminding me of falling in love.

Every trip down this valley road feels like finding a portal into another world where time, finally, has paused. Rather than play its usual role, ravaging artifacts — recklessly tarnishing silverware, sifting dust onto goblets, rotting lace tablecloths into so many doilies in an abandoned hall before guests can return to the scene of a glorious feast — time seems, fundamentally and ever so graciously, to give this place a wide berth. Though this landscape is the record of ceaseless erosion, the essentials remain stable on a human scale: silver-green sage below red rock and blue, blue sky, a horizon so expansive that the unobstructed wind cleans your bones. A landscape where nothing is hidden.

“Home again,” I say from the passenger seat. Patrick smiles, and I reach across the center console to tuck my hand under his leg. He shifts his weight onto it, does this weird German-winking-with-two-eyes thing that I’ve learned to interpret as a sign of affirmation. Leaving one hand on the steering wheel, he slings the other behind my headrest. I squeeze it and turn to the window, let my senses roam over moon-washed sandstone.

Climbers of a certain age around here use magazines and campfire conversations to bemoan two things: an increasing crowd and a corresponding decrease in the sharpness of now too-oft-climbed splitter lines. In the decade that I’ve been coming here, I’ve hardly found these trivialities worth complaining about.

But it’s not just the climbers who give each other shit. There are the accusations that outdoor recreation is empty consumption under a different guise; there is my pale skin, which some people with thousands of years of unbroken local ancestry consider to be proof that I can’t know what it is to love this place. There is my bright, tattered clothing, glared at like an enemy flag by cowboy-hatted townies within a hundred miles — hell, five hundred miles — of this place. There are our conversations about all the heartless assholes in Washington, D.C.; there are all the endless ways we divide ourselves from each other and from our planet until all are wounded and vulnerable.

Yet this is also true: The scope of this wonderland can hold us all.

Into my thoughts, Patrick says: “Have you heard that the shale field here wasn’t worth anything before fracking?”

“They’ll frack somewhere else — this place is too remote to be worth it,” I soothe myself out loud.

The mission of the BLM, the organization that manages this place with or without the web of National Monument protections, is “to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations,” as stated on their web page.

Emphasis on productivity: While 90 percent of our public lands are available for drilling, only 10 percent are available for a focus on conservation or other values like recreation or wilderness.

Two and a half years into our current administration, the BLM began to downplay its involvement with sustainability. Instead of their mission statement, the organization now ends press releases with a recitation of their economic prowess, as reported in Outside Magazine in May 2019: “Diverse activities authorized on these lands generated $96 billion in sales of goods and services throughout the American economy in fiscal year 2017. These activities supported more than 468,000 jobs.” That activities on federal lands also create nearly one quarter of America’s greenhouse gas emissions remains unsaid. The BLM has never studied the climate impacts of their federal mineral leasing program.

I imagine the valley we’re driving through filled with fracking pads, this place scarred, shattered, to fuel a few days of Americans driving their SUVs to their cubicles, gas stations, grocery stores … gas stations again. Maybe a few weeks of people like me driving from the places they make their money to the places they want to be. I imagine the Bears Ears valleys abandoned, toxic, left gaping after every profitable drop of prehistoric sludge has been sucked out of their worthless beauty. What is now aboveground serves only to shelter and sustain the fringes of our society — recalcitrant desert creatures, cowboys, Native Americans, and us — the craze-eyed wanderers.

“There are so many parcels up already that no one wants,” I continue. “I heard something like 75 percent of the oil and gas leases the BLM has offered in the last decade weren’t even bought.”

Patrick is silent as I parrot this hopeful heresy. We both know the words are sand thrown to the wind.

Unfathomable distance separates me from corporate boardrooms, separates the silence of this place from the clamor of an insatiable ideology. These valleys stay as empty as they are because the way your skin softens after weeks of rubbing against sandstone can’t be sold. Because destroying the soul-scouring views that make being alive, even in today’s world, feel like a magnificent thing would undermine whatever sliver of market value this place has.

Patrick says, “You know that statistic — if it’s even true — doesn’t mean anything. One company, one billionaire’s ‘entrepreneurial spirit,’ and everything here changes.” I can hear the air quotes in his voice. In his mouth entrepreneurial is a four-letter-word; his teenage years spent reading Marx in southern Germany color his take on our beloved American Dream.

No. Anxiety twists. I want to open my mouth and let sand pour out, convince whatever powers that be with the wonder of this pile of granules, weathered from our world, proof that sharp edges can be sifted into softness, that they must leave this place alone. I almost think I can accept what’s out there — merciless forces grinding to eradicate health, beauty, anything that can be sold for momentary gain — if only I can always come back to this place. These cliffs, this light and wind, are essential to my art of living with the unacceptable. Without them, all bets are off.

I lean against the window and inhale desert equanimity.

We turn onto the dirt road leading to our camp, roll by its domestic scenes of homecoming. Metal clinks as silhouettes unload climbing gear, pull pots and pans from car trunks, pop tabs on beer cans. No faces are blue-lit by that one glow we all know: Cell phone service stops on the other side of that portal, up there where the straight road begins to dip and curve.

Our headlights sweep the signpost for Site 12, home to the piece of earth I stood on as I first shook Patrick’s hand. We sat together on my tailgate that night until a spreading gold light haloed the buttes and towers around us, and twenty months later we were married.

He looks over at me as we pull in now. The depth in his eyes, and the gentle smile steady on his face, tell me that he’s thinking of that moment too.

***

“Better a cruel truth than a comfortable delusion,” writes Edward Abbey, red-rock godfather of what is sometimes called ecoterrorism.

In 2008 — thirty-three years after the publication of The Monkey Wrench Gang, Abbey’s speculative novel detailing the rogue demolition of Glen Canyon Dam — Tim DeChristopher completed his own journey from comfortable delusion to cruel truth. Perhaps better known as Bidder 70, DeChristopher first walked the line between these two extremes, and then he stepped right over it and into a prison cell. Turning a bidding paddle into a monkeywrenching tool, DeChristopher outbid oil and gas companies in the leasing of sizeable chunks of public land bordering Canyonlands National Park in southern Utah. The problem? He couldn’t pony up the 1.8 million dollars his paddle promised.

Before single-handedly shutting down the second Bush Administration’s last-ditch attempt to hand over huge swaths of Utah’s public land to energy giants, DeChristopher had lived a comfortable life. Everything changed on the day he attended a presentation by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in Salt Lake City. After the presentation, he approached one of the IPCC report’s lead authors. DeChristopher’s faltering verification of the facts she’d presented ended with her hand on his shoulder as her words shattered his world: “I’m sorry my generation failed yours.”

The data she had presented showed conclusively that if emissions didn’t peak by 2015 the planet would become unrecognizable. This realization, “of how fucked we are in our future,” empowered DeChristopher to engage in activism outside the law — he had nothing left to lose. “That’s how people have been oppressed in this country, through comfort,” he later reflected. “We’ve been oppressed by consumerism. By believing that we have so much to lose.”

Lewis Mumford, an American intellectual of the twentieth century, called this the magnificent bribe — we can hold on to our material gains, our comparatively widespread ability to eat like pharaohs day in and day out, the immediate gratifications of sleek gadgets connected to an infinite network of stimuli, as long as we don’t question where these things come from, where they are taking us, and what costs their barcodes conceal. As long as we hold on, white-knuckled, to what we have.

But what if we let go? DeChristopher was dumbstruck at the auction taking place despite an unresolved lawsuit over its legality, but it wasn’t until he saw a friend across the room openly weeping that his outrage boiled over. The sterile transfer of these beloved landscapes became suddenly, simply, unacceptable — no longer to be lived with, regardless of how artfully he might try. DeChristopher began to bid on parcels, driving prices up from as low as $2 an acre to close to $240. Eventually he was bidding on, and winning, every single parcel.

The auction erupted in chaos before being shut down due to price inflation. But before a new auction could take place, the courts ruled on a pending lawsuit: the BLM and the Bush Administration had cut too many corners in their review of the lands placed on the auction block that day. The leases of 77 parcels were stopped as a result of the auction’s illegality.

Nonetheless, DeChristopher was indicted on two felony counts and spent two years in jail. He noted that “the legal pathways available to us have been structured precisely to make sure we don’t make any substantial change.” Unlike Klapstein, the valve-turner, DeChristopher is not elderly, nor is he retired, though he is white. In his world there are no excuses for inactivity: “I feel like the goal should be to get other people in prison,” he stated in an interview with Terry Tempest Williams. “How do we get more people to join me?” He concluded, “Well, everybody has a reason why they can’t.”

I ask myself: If more of us were behind bars, what would change? And: What is the reason why I can’t join DeChristopher?

***

“It’s useless to put a Band-Aid over a gunshot wound.”

After the drive, my body begs to move. Gravel crunches under the worn treads of my shoes as I set off to make the rounds around camp. Two dogs bark in concert. A rabbit materializes to my left, careens toward the ribbon of cottonwoods that shelters the now dry wash to my right. Two sides of the campground are open to bounded sagebrush flats, while the third and fourth are defined by a shallow wash and a squat, honeycombed cliff pocked with surrealistic huecos. Twilight campfires have been built against piercing desert cold; they alternately shadow and illuminate these beguiling structures. An engine backfires.

I walk by a couple of campsites, one still emptily waiting for its homemakers to return from the cliffs, the other wafting the scent of onions toward the road. I see a car I know. The trunk of Matt’s candy-red Toyota Yaris hangs open as he rummages amongst the boxes piled there. I approach as he straightens up, hear him humming, and soon am near enough to see the light in his eyes switch when he recognizes me:

“Fancy meeting you here!” His eyes flick to my bloodied hands. “Been here awhile, eh?” It’s not uncommon for Americans around here to affect a Canadian accent — most of us have traveled enough to be self-conscious about our position in the world’s perception, even here in the U.S.

“Just today, but I kind of got my ass kicked.”

“Welcome home.” He grins.

We high-five and he asks what my plans are, meaning where I want to climb tomorrow. From time to time I blow up a boat here or pack a bag for a few days of wandering, but the siren call of these cliffs is an earworm I’ve befriended. We discuss options; Matt rubs his hands excitedly together between most sentences.

“I’ve got until Tuesday,” he says. “Three days, I think.”

“Headed back to Grand Junction?”

“Mm-hmm.”

Matt works for a friend mixing watercolor paints a few days of most weeks. He lives in his Yaris the rest of the time. It looks small next to most other cars out here, almost as if it’s about to crawl under the hulking belly of the adjacent Tacoma, Sprinter, or EuroVan. Matt always points out wryly that he took the passenger seat out to make more room for sleeping — roving itinerants transition slowly, if at all.

Later, around a leaping fire, while tendrils of flame determinedly create a galaxy of embers, we get into it again.

“At least he did it,” Sam points out. Last year he would have sounded reverent. “He made it a National Monument.”

“That fucking bastard, he better have,” Matt mutters. More loudly now: “After eight years of his weak-assed bullshit. He disillusioned a generation. No one over there gives a shit about this desert anyway.”

“Still,” Kristin interjects. “Now it’s a National Monument.”

“Not for long. You know nothing valuable is safe in this country.”

“I do now.”

“Come on, guys,” Matt cajoles. A long pause. “I’ve got something goo-ood,” he sings, his teeth glistening. The bottle he pulls out of his pocket sloshes, winks amber in the firelight. He takes a sip and passes it on before musing, “So what if the Monument gets reversed? We can scale the cliffs and drop boulders on any rigs that drive in here.”

“You want to go to jail?” I ask.

He sees that I really want to know and doesn’t respond.

“Not worth it,” Zack interjects. “They’d just be back the next day, making their money while you rotted in a cell. It’s useless to put a Band-Aid over a gunshot wound.” He cocks his head. “Plus, they’re drilling all over the place already.” A pause. “And we all drove here.”

Joyless half smiles spread around the fire as sighs mingle with the sound of popping wood. People who have time to live in places like this for weeks on end tend to be academically educated; awareness of our complicity is a festering thorn pricking all ideas of salvation. The footing is precarious when you try to stand for something that makes you a hypocrite.

“So then, what?” asks Patrick.

“Whiskey! And climbing, duh.” Matt sips, swallows.

Silence.

Looking toward the wash, I remember the silk of flood-fresh earth giving way under my feet to rise up between my toes. Recreation recreates connection, connection that binds and entails. I don’t just come here to play. These lands invite my unspooling; in unflinching desert light, the atoms usually thought of as mine dance wherever I look. My home is an ecosystem, no less so because my government mines it — undermines it — to power my lifestyle.

I don’t know how to say this, or what to do about it.

Sighing, Zack takes a swig from the bottle and then howls into the night sky. People are always howling around here. My eyes slide to the crescent moon, and I tip my head back and open my throat too, thinking of the confetti that shoots out of a clown’s kazoo. It took a good long while for this place, these people, to move me beyond looking askance at acts of abandon.

As our howling fades, distant yipping becomes audible. Everyone grins, and a few howl back; coyotes are beloved in this crowd, the voice of the desert, subversive as grass. The fire sways and jettisons embers. Our conversation loops from climbing dreams and nightmares to the Paris Agreement on the climate, back again, and onward to wealth inequality, to the twelve years climate science gives us to undercut emissions and the twenty-year term of BLM mining leases — but then back, always back, to climbing, to what pulls us here, there, weaves theres into heres, endlessly invites us out of our skin-sized kingdoms.

After the fire has finally sizzled into silence, Patrick and I lie under a pile of blankets, turned toward each other in the darkness.

“Do you really think the National Monument will get canceled?” he asks me, his imperfect English so sweet that I reach to thumb the hollow of his palm. I try not to answer, but he nudges my bare foot with his.

“I do.”

He pulls my head into his chest, resting his chin in my hair. I remember being here a month or two after this place was declared a Monument, how giddily we’d celebrated and how contentedly, easily, we’d fallen asleep. Tonight I am witness as Orion slides across his domed expanse.

***

“‘No’ is only the prologue …”

Obedience comes from the Latin oboedire. Ob: toward. Audire: listen, hear.

Civil disobedience, then, is the act of not listening to society. From a position of not-listening, action slips outside the categories of obedience and constructed legality. Perspective shifts as listeners crane in one direction or another — yesterday’s criminals are tomorrow’s heroes.

It is possible to break the law without being disobedient, and to disobediently follow it. There are no bystanders.

Embodied through the acts of hearing, listening, we acknowledge: Human, I am a part and not apart. To obey is to be present, to show up. It is to offer attention as love and to refuse to stop; it is to stay conscious and enraged.

Donald Trump did reclassify Bears Ears on December 4, 2017. His proclamation, currently in litigation, reduced the protected area by 85 percent — from 2,112.264 square miles to just 315.

In late 2018, Zinke became the fourth cabinet member to resign amid accusations of ethical violations. While the Justice Department investigated Zinke’s role in a land deal with energy giant Halliburton in his home state of Montana, Trump praised the departing secretary. Zinke’s legacy endures.

My global community speaks of holding actions, of standing up to say no, of throwing bodily wrenches, scooped handfuls of sand, into the unmanned machine of corporate capitalism. Prison sentences tell us: Today it is a crime to listen to our ecosystem, to hear our simple human needs. Yet environmental groups grounded in civil disobedience multiply, and they inspire. Extinction Rebellion, Fridays for Future, Ende Gelände — a new obedience, a fine-tuned listening, takes to the streets. If the dominant society is on autopilot, direct actions that, yes, can end in jail, create the space of a pause where new structures and patterns of a life-sustaining system can grow.

But grow they must. No is only the prologue. Storytelling is an action; narrative taps our ability to change. We need better stories, stories of where we want to go.

Art is activism if it wins people over, or helps those of us already here to go on. Listening to a true story, though it is one of loss and indictment, can become art that unhardens hearts, art that reminds us what it is to be human and how this is like being everything else. There might be more effective ways to fight than fighting.

Hypocrite though I remain, I listen, and I hear. I hear this: living with the unacceptable is not yet optional. It is here, there, around us and within us. Acknowledged, a whisper becomes a shout: to live with the unacceptable is to shape it anew.

This wonderland can hold us all.

********************************************************************************

Miranda Perrone is a writer, philosopher, environmental scientist, and activist whose work seeks to feed socioecological change. Her recent writing can be found in Waxwing, The Rumpus, and Terrain.org, where she also now curates audio content.